Steve Mitchelmore responds to my recent interviews at This Space.

Economic anxiety came suddenly upon me and all too close … then suddenly confusion [war and revolution] broke loose … I produced more powerfully than ever, but more than ever like a dying man. In the direction of Christianity it is the highest yet accorded me, that is certain. But in another sense it is … to high for me to assume responsibility and step forth openly in character. That is the deeper significance of the new pseudonym [Anti-Climacus], who is higher than I.

Kierkegaard, Journals

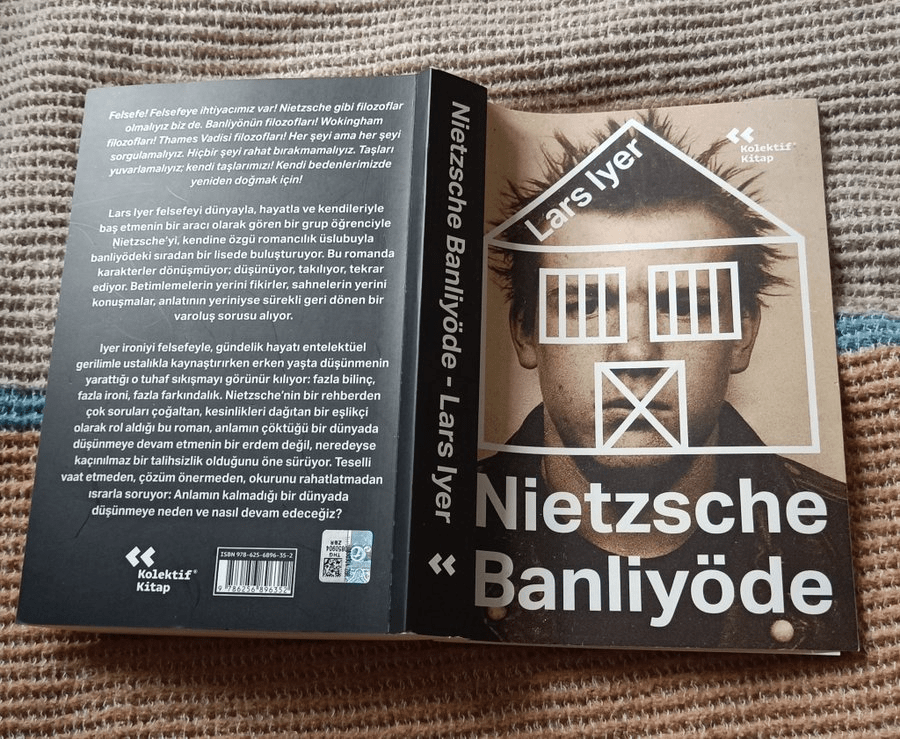

Review of Nietzsche and the Burbs from the Sunday Times, 5th January 2020:

A rock-music caper loaded with adolescent yearning.

Houman Barekat

Lars Iyer is not one for changing the record. Between 2011 and 2014 he published three short, satirical novels inspired by his time as a philosophy lecturer. The Spurious trilogy affectionately skewered the pretensions and anxieties of over-earnest intellectuals; a fourth nove, 2016’s Wittgenstein Jr, ploughed a similar furrow. The theme is reprised in Nietzsche and the Burbs, albeit this time by focusing not on cloistered scholars but a gang of sixth-formers at a comprehensive in a Thames Valley suburb.

The narrator, Chandra, and his pals, Art, Merv and Paula, are united by a hatred of all things mainstream. When they’re not tormenting their teachers with precocious backshat or sabotaging the annual cross-country (‘Sure, we could have run. But we chose not to, like gods’), they enjoy knotty discussions about madness, suicide and the climate apocalypse.

They befriend an engimatic new boy, whom they nickname Nietzsche on account of his brooding demeanour and love of philosophy, and invite him to join their dodgy band as lead singer. The group, rechristened Nietzsche and the Burbs, is plagued by creative differences: ringleader Art – who regards potato chips as ‘false consciousness’because they keep the masses happy’ – wants them to play ‘tantric dub metal’; Paula denounces this as ‘aural wanking’ and would rather make music people can dance to.

Iyer’s co-protagonists don’t entirely convince as a depiction of contemporary youth: when Chandra declares that ‘No one will ever have been more bored than we are. More purely bored’, he sounds more like a 1970s punk-rocker than a 21st-century digital native. Their cud-chewing – on the redemptive power of art, the yearning to transcend the banality of modern existence and so on – grows wearisome.

But Iyer does a good line in pithy dialogue, and the landscape of late adolescence is evocatively rendered, encompassing everything from the ‘Hieronymus Bosch grotesquerie of the PE changing rooms’ to the thrill of anticipation of nights out: ‘Why not secede, sit life out, bury ourselves in our bedrooms? Because of possibility. Because of what might happen’.

Deep uni posturing (Times Literary Supplement)

Simone Weil comes to Manchester in Lars Iyer’s latest campus novel

The new field of “Disaster Studies” is booming in Lars Iyer’s sixth novel, My Weil. It is a product of the philosophy department at Manchester’s fictional “All Saints Uni”, which, as police helicopters patrol the increasingly dysfunctional city, is home to academics on the make, busily turning “the end of the world into an academic fuel”. The coming apocalypse is full of promise and, if exploited correctly, might propel Disaster Studies students into academic jobs. The trouble is, as the narrator, Johnny, acknowledges of himself and his fellow PhD students, “we’re actually disastrous”.

Johnny and his peers are too busy keeping the “afternoon terrors” of the humanities at bay, by “day drinking” at “Ruin Bar” and filming re-enactments of scenes from Tarkovsky, to work on their dissertations. In their midst, meanwhile, Business Studies postgrads make “a mockery of the PhD student” with their focused, goal-orientated study. “Where’s their doom? Where’s their crushedness? Their diseases of the soul?” The Business Studies students seem oblivious to the fact that a PhD requires nothing short of “reinvent[ing] philosophy all by themselves, or whatever it is we’re doing”.

The arrival of a new student who wears nun shoes and calls herself “Simone Weil” does little to address their tormented procrastination. It does, however, add a new dimension to the day drinking, as Simone (who sticks to mineral water), with her unwavering belief in God and the triumph of good, provides a foil to the bleak outlook of the Disaster Studies cohort. The introduction of such a character is typical of Iyer, and My Weil completes a trilogy of sorts, following the author’s fourth novel, Wittgenstein Jr (2014), which features a young Cambridge Professor of Logic dubbed “Wittgenstein”, and his fifth, Nietzsche and the Burbs (TLS, February 7, 2020), with its suburban sixth-former nicknamed “Nietzsche” for his nihilism. If Iyer’s admixture of philosophy and fiction is not exactly subtle, it is nonetheless good fun, and no more so than when it exposes the disjunction between the life of the mind and the contemporary university. We are in the world of the “deep uni”, where figures such as “Professor Bollocks” deliver, to Johnny’s dismay, compulsory PhD lectures on topics such as time management:

TIME! MANAGEMENT! TIME! MANAGEMENT! Within the walls of a uni! As if Henri Bergson never existed! Nor Martin Heidegger! As if Deleuze had never formulated the three syntheses of time!

The grandiose posturing of Johnny and his fellow postgrads is often just as absurd as the conditions imposed by the bureaucracy and management speak of the modern university. It is never quite clear who is responsible for the most bollocks, and Iyer is at his sharpest – and My Weil at its funniest and most moving – when simultaneously lamenting and ridiculing the tragicomic plight of intellectual life in the contemporary world.

[This written interview was the basis of an interview/ profile in The Morning Star in 2023. Here it is in full:]

You’re one of the few contemporary writers who can make me laugh on the 0630 bus. From your perspective, what’s the attraction of a comic approach and where is the humour coming from?

Is the comedy a (Beckettian) coping mechanism? A provocation? The only viable means of critiquing the devastating impact of C21st capitalism?

The novels are supposed to be fresh and funny: that first of all. Laughter is important – it’s necessary to breathe. ‘Everything I’ve written, I wrote to escape a sense of oppression, of suffocation. It wasn’t from inspiration, as they say. It was a sort of getting free, to be able to breathe’: that’s E.M. Cioran in an interview. For me, that getting-free involves laughter: laughing at the Man. Laughing at the madness. Laughing at the po-faced and humourless absurdity that is all around us.

The attraction of comedy: it allows some freedom, and perhaps might grant freedom in turn. A way of diagnosing what’s happening to us, but not being crushed by it. Perhaps it might be the beginning of a critique, which is only possible if we can find others to laugh with.

In My Weil (and throughout your fiction) there seems to be a genuine and deep-seated sense of despair below the erudite wit and sharp observations. Do you believe we’re doomed? If so, why? If not, what do you believe will save us?

Definitely despair. About what? Numerous disasters on the horizon; perhaps as disastrous are the means meant to solve them.

Problem: ecosystem collapse, soil microbiology exhaustion, insect biomass erosion. Solution: the seizure and financialisation of the global commons; nature valued as a natural asset which can then be managed, controlled and, of course, profited upon.

Problem: inequality. Solution: human capital investment, which is to say, opening a new futures market by betting on the life-outcomes of prisoners, refugees and welfare recipients.

Problem: the financial crisis, unpayable debt (53 trillion dollars worldwide and counting; 31 trillion dollars in the US alone.) Solution: the Going Direct Reset initiative, as agreed to by the Federal Reserve and the big asset management corporations at Jackson Hole, Wyoming in 2019. This will see the replacement of currencies with the Central Bank Digital Currency, allowing complete control over every transaction, cutting off the wealth of deplorables. Tyrants of the past only dreamed of such power …

Are we doomed? Not if we awaken to what’s happening. What will save us? Human unmanageability, perhaps. It’s just such unmanageability that is shown in my characters’ laughter, in their friendship. Internal struggles between various factions of the powers-that-shouldn’t-be, perhaps … Something contingent, miraculous, perhaps …

My reading of Spurious, Exodus and Dogma is that there’s a focus on individual despair. In My Weil there is a collegiate spirit, but it’s mired in chaotic inertia. To what extent does this reflect an implicit rejection of the possibility of intelligent and impactful collective action?

The characters in My Weil consider various possibilities for collective action. There’s becoming lumpenproletariat – living like the raggle-taggle of criminal-types, unmanageable déclassés that Marx wrote about, who keep to the shadows. There’s becoming apocalyptic – gathering like the early Christians awaiting the Second Coming; only this time, they’re waiting for an incoming, shattering transcendence that would explode the present order of the world. There’s secession – going under the state, on the model of villages in Alpine valleys that that have their own currency, that keep low-tech – using mechanics, not electronics; or those parts of Mexico that just do their own thing, regardless of central government decree.

My characters have little faith in present institutions. My question would be whether and how we might make them more accountable, transparent and democratic. My characters are tired of all that. They say they only want to let the present world go down. I’m not sure I’d take them at their word. Perhaps we can see a viable form of collective action – or rather, collective inaction – in their common drifting, their vagueness, their abandonment of proper ends.

I’ve seen reviews of your work in which it’s suggested characters are secondary to ideas and comic situations. I don’t accept this. The dialogue fizzes and – while your characters knock lumps out of each other, with serious discussion lurching into banter and then drifting into invective – you give some serious consideration to the themes of friendship and intellectual affiliation. In terms of the Disaster Studies PhD candidates in My Weil, is this driven by a fascination with these types of personal/professional relationship, or is it rooted in the sentiment reflected in an David Bowie song: “While troubles are rising we’d rather be scared together than alone”?

Being scared together: yes, that’s the thing. Despairing together. Sharing such moods, being humorous about them, comically exaggerating them, ringing changes upon them, which means they’re no longer solely negative. Things might seem hopeless, but hope is there in our capacity to talk. We might think that we that we can’t do much about the disasters ahead of us – about neuroweaponry or weather warfare, about education capture and health capture, about destabilisation agendas, about transhumanism, but we can discuss and diagnose them. Laughing together at their folly, shaking our heads together at their evil, we needn’t be merely passive victims.

To what extent is the rejection of plot in your six novels tied into your apparent fatalism about the future (of academia, of our culture, of humanity)?

No fatalism from me. And there is some plot, at least in the last three novels. The end of Nietzsche and the Burbs sees its characters high as kites, full of wild plans. They’re together, joyful, engaged in what anthropologist Victor Turner has called ‘communitas’: a radically egalitarian, non-hierarchical community of associative friendship.

Communitas, Turner explains, can never last; its liberatory joy must inevitably give way to a restoration of order, of the ‘societas’ of familiar social bonds and roles, the usual hierarchies. The question my characters begin to ask concern the relation between the joy of communitas and the societas to which they have to return.

In My Weil, my characters, equipped with their studies in philosophy, are better able to consider this question. True, they don’t formulate it as such, but they’re constantly thinking about ways of escaping the system. The opposite of fatalism!

Focussing on your satirical take on academia. It’s particularly sharp in My Weil: how much of an exaggeration is Professor Bollocks and the notion of ‘accountability buddies’? Is it really getting worse? [I’m particularly interested in this because, in the 1980s, under the Thatcher government, I worked in an Alvey-funded AI project – each of the research teams in receipt of his funding was monitored by a figure called an “industrial uncle” (sic). I wonder if that was when the Bollocks began in earnest?]

An ‘industrial uncle’: wonderful! – I’ll borrow that. Nothing of the novel is exaggerated. The language of management theory has colonised the university. Expressions like ‘best practice’ and ‘seedcorn funding’, used without irony … No one laughs or rolls their eyes … Everything, taken straight.

In academia, at all levels: the emphasis upon self-motivation, self-directed action, self-management. The student, the academic as a self-initiating entrepreneur, realising themselves as a piece of human capital; as an economically significant commodity … Management is the task, distributing resources, actions, practices to make them more efficient, more productive. As if every problem that counts could be solved through administrative power – through correct implementation of the system.

The logic here is technological – it reflects the deepening of the technological system so well diagnosed by Jacques Ellul. Systematisation, schematisation, tabulation, bureaucratisation, qualification, rationalisation, mechanisation, standardisation, materialism and scientism: that’s what’s at work. The bollocks began long ago. To make it worse, this process of stripping away meaning, comradeship, a sense of the absurd is accompanied by the grotesque parodying of the same notions that this process hollows out: to the university as your ‘family’, to your fellow students as potential ‘buddies’, etc.

My characters, in response, cultivate counter-techniques of failure and ineffectiveness, of wandering and vagueness and of displacing ends from means. They aim at a deliberate incompetence, in which not finishing your PhD dissertation is more of a sign of honour than completing it on time; in which failure is a better sign of scholarly integrity than system-rewarded success. And they laugh – they have fun, which is pretty much forbidden in these over-serious times.

I’d argue that all six of your novels are literary fiction / new weird hybrid – based on the criteria of “[exploring] the boundaries of reality of reality and experience through philosophical speculation” (Jason Sanford, 2009). This is notable in My Weil, particularly in the supernatural (maybe?) sequences set in the Ees. [Would you be happy with the label critical realism?] Did this approach an emergent property of the subject matter, or is it a style of writing you particularly enjoy?

The Ees, a scrap of woodland in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester – meant to resemble the Zone from Tarkovsky’s film Stalker – permits the wandering and vagueness, the displacement of ends from means to which I have referred. It’s about dis-activation, which is why it’s full of all kinds of junk.

As such, the Ees is an embodiment of the students’ relationship to their PhD dissertations and, more broadly, to study. It allows them to be stupid, ignorant, disoriented – but in a positive sense. In an antidote-to-Professor-Bollocks kind of sense.

No coincidence that the character most strongly linked to the Ees is least committed to finishing his dissertation. In all things, romance included, my protagonist Johnny’s aim is to stay with potential without submitting it to an purpose, without actualising it in any course of action. And in the end, the Ees seems to ‘reward’ Johnny by letting him dwell permanently in the suspension of development.

Why Manchester? What fascinates you about the music and culture of that city in the 1980s?

The Manchester I discovered when I moved there in 1989 still had areas that were like the Ees of the my novel: unproductive areas, temporary autonomous zones such as the Hulme Crescents, an edgy zone of low-rise, system-built flats. They’re described an excellent recent article in The Guardian, and which I’ve tried to write about in my own way. It was from such places that so much great mancunian culture came.

Manchester was regenerated in the ‘90s. Investors and financiers, gentrifiers and speculators, transformed the cityscape with statement architecture, with steel-balconied warehouse conversions: monuments to cheap credit. My characters dream of battering back the mancunian regenerators, of re-opening the figurative cracks and the crevices where you used to be able live unnoticed and unbothered on government benefits. Only the Ees is left to them of that world now – the Ees and the great mancunian music to which they still listen.

What attracts you to the philosophers featured in your second (loose) trilogy, Wittgenstein, Nietzsche and Weil?

All of them I regarded as philosophical ‘enemies’ – thinkers who were, I thought, were remote from my own philosophical allegiances and concerns, but with whose work I nevertheless wanted to spend time. And I’m glad I did. You sharpen your thought by working with what you’re against …

You’ve written two books on Maurice Blanchot – is he a thinker you believe can have a transformative impact on life in the C21st? Why?

Blanchot’s a subterranean influence on so many thinkers – think of Marcuse’s notion of refusal, for example. Currents from his thought run everywhere.

What led you from philosophy to creative writing? What can fiction achieve that philosophy can’t?

- M. Cioran says regarding his own break with philosophy: ‘I realised that in moments of great despair philosophy is no help at all, and offers absolutely no answers. So I turned to poetry and literature, where I found no answers either, but states of mind analogous to my own’.

I don’t quite agree: philosophy helps in diagnosing the causes of despair, and thereby achieving some distance from the horror. Philosophy is about self-knowledge, but this is not about our inner selves so much as learning about how our inner selves are constituted. It is in this way that philosophy can provide answers about the sources of despair – about the sources of joy, too; about the meaning of friendship, about Turner’s notion of communitas and its relationship with societas.

But I agree with Cioran about poetry and literature, which can embody despair so directly, making it tangible, real. And I admit that sometimes philosophy is of no help. I want company. Thank goodness for Dostoevsky, for Mann, for Beckett, for Duras, for Blanchot, for Lispector, for Cixous and the others. For Bernhard above all! No doubt they’ll ban him soon …

In My Weil, Marcie veers from enthused earnestness to heartbreaking cynicism to naïve absurdity. Is this a satirical take on the trials and tribulations of writing a doctorate or a metaphor for the competing identities of higher education?

Although they have each other, my characters become increasingly deranged by what they fear. They know so much about what’s going on – about, say, the dangers of surveillance: behaviour tracking, compliance tracking, predictive analytics (‘pre-crime’), warning us when and where lawbreaking will emerge; even prescriptive analytics: programmes to prevent the possibility of that emergence, sending in robot dogs and supersoldiers to where our masters think a rebellion might break out; locking down the population of a troublesome district just in case …

Marcie’s Vision, capital ‘V’ – you’ll have to read the novel for context – shows her even more. She discerns the coming internal surveillance, too: synthetic biology that could see so-called ‘electroceuticals’ introduced into the bloodstream, keeping an eye on our insides. She senses the possibility of the live-editing of our DNA – of the so-called improvement of the human genome to make us more compliant, more useful. Just right for when attention turns from the enemy without to the enemy within, treating us all as potential threats to be neutralised in advance.

There’s more, much more, that Marcie sees. It’s unbearable. All she can hope for is human unmanageability, which she understands as the capacity to love …

Nothing satirical intended with my depiction of Marcie, who tries to revive a myth of sorts, the story of the Antichrist, to give her a sense that something might be done, to inflate the issue to the level of the cosmos …

An A to Z of Spurious (2011)

I hope Spurious can be enjoyed by a reader entirely unfamiliar with the names and ideas mentioned in its pages. In large measure, I think, it is the way W. and Lars enthuse about a scholarly project or a specific thinker that makes the novel entertaining (if indeed it is entertaining). On the other hand, perhaps there is something to be gained from focusing in a little more depth on some of the recurring ideas, names and objects in Spurious, since they are not entirely arbitrary. That is the aim of this A to Z.

I have underlined all words in the following entries that are covered elsewhere in the A-Z, in order to facilitate hyperlinking.

A is for …

Peter Andre, 1973-

Australian born singer and television personality, known for his huge hit ‘Mysterious Boy’ and his Reality TV assisted comeback, which saw him meet and subsequently marry Katie Price, AKA Jordan. They have since divorced.

Lars reads about the exploits of Peter Andre and Jordan in his gossip magazines.

Apocalypse

The end of times; violent, climactic events. Etymologically, the word suggests a lifting of the veil, a revelation of a hidden truth. Thus, the Biblical prophet vouchsafed an apocalyptic vision learns something of God’s plan – for example, how the wicked will be punished. As such, for the righteous the apocalypse is entwined with a sense of hope: the destruction and suffering to come may well make room for the coming of that restorative figure called the Messiah. More loosely, any event that sees the overturning of the security and predictability of life can be seen as apocalyptic – for example, climate change or the current financial crisis.

Lars, according to W., has a particularly keen sense of the apocalypse, but lacks what, for W., is the intertwined hope that he calls messianism. This might well be due to Lars’s Hinduism, W. says.

W. credits Rosenzweig with having a particular insight into the apocalypse, perhaps because of his experiences in World War I.

B is for …

Benjamin, Walter, 1892-1940

German Jewish critic and philosopher. Friend of Scholem and mentioned in passing in Spurious. Benjamin is famous for combining ideas drawn from Jewish messianic thought and Marxism.

W. compares Lars’s sagging trousers to those of Benjamin, which, in what W. calls a well known photograph (I’m not sure if it’s the one above), are pulled up tight around his waist.

Brod, Max, 1884-1968

Writer friend of Kafka and famous for refusing his friend’s request that his manuscripts be burned after his death. Brod’s renown in his own lifetime – he was a prolific author across a number of genres – has been almost entirely eclipsed by those he generously supported, Kafka among them. Brod encouraged his friend in his writing, and eventually oversaw the posthumous publication of The Trial, The Castle and America and other works in contravention of Kafka’s wishes. He wrote several works on Kafka, in the form of biography and fiction, proposing a pious, almost hagiographical, interpretation of the life and work of his friend. Brod has not been forgiven for this by legions of Kafka’s admirers. In a famous essay on Kafka, Benjamin called Brod a ‘question mark in the margin of Kafka’s life’.

W. and Lars wonder which one of them is Kafka, and which Brod, before entertaining the troubling idea that they might both be Brod, and altogether lacking a Kafka.

Blanchot, Maurice, 1907-2003

Eminent French novelist, literary critic and philosopher. A concern with the significance of speech, and its relation to networks of power, is, arguably, as abiding in Blanchot’s work as his better known interest in writing. In this regard, Blanchot bears the influence of his lifelong friend Levinas. Blanchot was also part of the group of intellectuals and activists who met in Duras’s flat on the rue Saint Benoit, and he was a friend of Dionys Mascolo.

W. and Lars discuss the photograph shown here of Levinas and Blanchot, reproduced in Salomon Malka’s biography of Levinas. Levinas is at the top of the picture, with Blanchot seated to his right.

C is for …

Canada

W.’s utopia, where he spent much of his childhood and to which, through numerous job applications, he has tried and failed to return.

Cawsands

Town in southwest England, reached from Plymouth by passing through Mount Edgcumbe. W. and Lars visit a pub there.

Cohen, Hermann, 1842-1918

German-Jewish Neo-Kantian philosopher, who, in his late work, argued for the ethical significance of Judaism. His account of what he called the correlation of God and human beings, whereby, although independent, they reciprocally determine one another, was very important to Rosenzweig’s thought.

Also notable in Cohen’s work is the role of prophetic messianism, which sees the defeat of injustice in the movement towards the realisation of ideal ethical laws.

W. finds Cohen’s work particularly suggestive regarding the notion of the infinite.

Conic Sections

A conic section is any of a group of curves (circle, ellipse, parabola, hyperbola) formed by the intersection of a right circular cone and a plane. Originally studied by the ancient Greeks, Kepler found an important scientific application for them in the seventeenth century when discovered that planets move in ellipses.

W. reads Cohen on conic sections, and dreams he might himself become the philosopher of conic sections just as Lars might become the philosopher of the infinitesimal calculus.

D is for …

Damp

Moisture on an inner surface of a building, promoting the staining of walls by salt and mould. Leads to the loosening of wallpaper and the rotting of wood, and sees paint and plaster flaking away.

Damp has a number of causes: condensation damp comes from water vapour in areas of the building where air doesn’t circulate; penetrating damp results from precipitation entering an inner surface as a result of faulty roof flashing or missing pointing; and rising damp is caused by capillary action dragging ground moisture up a masonry wall.

The cause of damp in Lars’s flat is, however, mysterious. Although we see W. helping Lars to clear the kitchen and bathroom in the flat in preparation for the application of a damp proof course, it appears that this remedy fails. The kitchen remains damp, and there is still the sound of rushing water. We next learn that the ceiling has been taken down, and new joists installed: presumably some kind of leak has been fixed. But the sound of streaming water persists. No amount of dehumidifying and fan heating seems to make any difference to the damp, which Lars calls his apocalypse.

Deleuze, Gilles, 1925-1995

French philosopher mentioned in passing in Spurious. Lars justifies his inactivity by comparing it to the ‘five year hole’ in Deleuze’s career. Deleuze actually refers in an interview to an ‘eight year hole’, the gap between his monographs on Hume (1953) and Nietzsche (1961) in which he was busy teaching in the lycées and working as an assistant in the history of philosophy at the Sorbonne. Deleuze’s expression is borrowed from F. Scott Fitzgerald, who writes of a ‘ten year hole’ in one of his short stories.

Dundee

Scottish city on the Tay estuary, the fourth largest in the country. It seems to enjoy a microclimate that, while it is in the far north of Britain, makes it surprisingly warm and bright. This is why Lars puts on his sunglasses, which W. so despises, on their visit to the city.

E is for …

Esteem Indicators

Marks of respect from scholars and researchers in a particular academic field, including awards, fellowships of learned societies, prizes, editorial roles, conference organisation, positions in national and international strategic advisory bodies etc.

W. suggests that Lars, who lacks any of the above, fill in humiliation indicators instead.

Europe

American readers might find it surprising that the British speak of Europe as though they didn’t belong to it. But Europe, to the British, is invariably continental Europe, i.e. over there, across the channel.

W. and Lars also speak of Old Europe – a sense of culture and history very different from that in Britain. Indeed, they claim that the British no longer live in history. They feel they will never be part of that milieu from which the thinkers they admire emerged, neither speaking its languages nor having the necessary depth of scholarship and religious feeling.

F is for …

Flat, The

Lars owns a damp-ridden flat, the floors of which noticeably tilt because the flat was built above a mineshaft. The damp in the kitchen has long since prevented the electricity in there from working. Behind the flat, there’s an equally grotty yard. Sal refuses to visit Lars’s flat, and W. does so only under protest.

Freiburg

Full name: Freiberg im Breisgau. Small city on the edge of the Black Forest in the southwest of Germany. Freiburg was known as the ‘city of phenomenology’ in the 1920s, with Husserl and then Heidegger holding university Chairs there. Freiburg was painstakingly reconstructed street by street, house by house, after extensive bombing during World War II.

The Fish Quay

Historic part of North Shields, a small coastal town to the east of Newcastle, on the Tyne. Ferries run from the nearby terminal to the Netherlands (not Norway, as W. and Lars seem to think).

Friendship

W.’s touching faith in friendship and love can seem at odds with his perpetual hounding of Lars. But nagging, he says, is part of friendship; how else might friends push one another to greatness?

W.’s plan only to publish with his friends has led him into difficulties with his editor, whose publishing company seems to have failed, resulting in W.’s book having gone almost immediately out of print.

G is for …

God

The characters cannot but struggle with the idea of God. They are not, in any usual sense of the word, men of faith, but they do see themselves as, in some measure, religious: that is, they feel a kind of religious pathos. Alas, this is not enough to save them from atheism.

Golem

In Jewish Folklore, an anthropomorphic being brought to life by supernatural means. In some stories, the Hebrew word ‘truth’ needs to be written on the golem’s forehead in order to animate it. Other stories tell of writing letters on a piece of parchment, which is then placed inside the golem’s mouth in order to bring it to life.

Godspeed, You Black Emperor!

Canadian post-rock band, known for writing long instrumental songs making use of sampled sounds. ‘Dead Flag Blues’, which W. continually plays to his students, is the opening track on F♯ A♯ ∞ (F sharp, A sharp, infinity) from 1997.

Gossip

Lars is much given to reading downmarket gossip magazines (‘chav mags’) about celebrities, which W. finds particularly exasperating.

Greek

W. has tried several times to learn classical Greek, but has been defeated each time by the difficulty of understanding the operation of the aorist, a form of the verb that expresses action without indicating its completion or continuation. At one time, W. and Lars studied Greek together, but Lars, according to W., only retained one word from these lessons: omoi. Lars is said to have used classical Greek in one of his moments of illumination.

H is for …

Hinduism

Ancient religion of the Indian subcontinent, characterised by a belief in reincarnation.

Lars is Hindu, and exhibits what W. calls Hindu fatalism – the sense that what is to happen is preordained. Presumably this is one of the things which, for W., gives Lars his vivid sense of the apocalypse. At the same time, W. insists that the Hindu never really experiences the apocalypse. He argues that whereas for the Jew and the Catholic, time is linear, and the End Times really are the End, for the Hindu, time is cyclical. According to Hinduism, our age might indeed be the End of Times, but it will in turn be superseded; after the destruction will come the great flood from which the universe will be reborn. So Hindu fatalism is, W. argues, a comfort. At the same time, W. notes, with the idea of moksha (see below), Hinduism does promise a release from the cycle of life and death, providing a second kind of comfort.

Lars, according to W., has tried and failed to become a significant scholar of Hinduism.

Howard Hughes, 1905-1976

Aviator, film producer and director. Hughes suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder, once occupying a screening room in a film studio for four months without leaving, living only on chocolate and milk and relieving himself in empty bottles. He did not cut his hair or nails in this period. In his later life, he became a recluse, living in hotel penthouses around the world. When Sal’s away, W. fears he’ll give in to his agoraphobia, turning into a scholarly Howard Hughes.

I is for …

Idiocy

Alleged state of W. and Lars in Spurious. W. claims Lars’s idiocy is the simple absence of thought, whereas his idiocy is the result of indolence. Either way, W. says that he and Lars share the fact that they have always known they were idiots, even as they’ve endeavoured to struggle against their idiocy.

Illness

The great figures that the characters in Spurious admire were often ill: Kafka died at 42 of tuberculosis; Rosenzweig, locked in by paralysis years earlier, succumbed to ALS aged 40; a botched medical procedure left Blanchot incapacitated for much of his very long life. W. and Lars suppose that the illnesses in the thinkers they admire was linked to their ability to think. A tempting idea, but the characters’ illnesses (coughs and colds) are not, alas, similarly productive.

Infinite judgement

A logical classification which appears in Kant’s typology of judgements in the Critique of Pure Reason. In Religion of Reason, Cohen discovers in this notion a positivity prior to both affirmation and negation – that is, to a superlative or transcendence which he links to a certain conception of the negative in ancient Greek thought. This leads W. to conclude that the in- of infinite should not merely be understood privatively (that is, as a mere lack of finitude); there is a positive sense to the word, too.

The Infinitesimal Calculus

Branch of mathematics comprising differential calculus and integral calculus developed by both Leibniz and Newton in the 1660s. The method of infinitesimal calculus, based on the summation of infinitesimal differences, has been treated sceptically by mathematicians and philosophers. However, Cohen made use of it in his discussion of the existence of God, influencing Rosenzweig. W.’s enthusiasm for Cohen’s discussion of the infinitesimal calculus is tempered by his inability to understand it.

J is for …

Jordan, 1978-

British celebrity and TV personality. Former glamour model.

Judaism

The main philosophical source for the ideas discussed in Spurious is the thought of those German speaking Jews who sought, early in the twentieth century, to address a crisis of traditional values.

Rosenzweig, Scholem, Benjamin and others share the view that the human suffering caused by World War I spelled the end of a simple faith in historical progress and the meaningfulness of history. More generally, they concur with Nietzsche that our time is marked by the ‘death of God’, a collapse of those traditions that made sense of the world, although they do not draw the same conclusions from this as Nietzsche did.

It is primarily with the thought of Rosenzweig that Spurious is concerned. In response to Nietzsche’s challenge, and under the influence of Cohen, Rosenzweig attempts to unfold a hidden, utopian dimension of Jewish messianism that creatively interrupts linear history. Scholem and Benjamin have similar ambitions. In his letters to Rosenstock, a Christian convert, Rosenzweig argues that Judaism is exemplary for the rest of humankind in its preservation in liturgy of its peoples’ relation to God.

Scholem and Benjamin follow some aspects of Rosenzweig’s thought in this regard. Levinas and, in his own way, Blanchot do the same in the second half of the twentieth century.

W. has a Jewish ancestry, although his family are converts. He is, among other things, a scholar of ancient Hebrew.

K is for …

Franz Kafka, 1883-1924

Prague born Jewish writer. Kafka’s unfinished, posthumously published novels The Trial and The Castle and Kafka’s many stories, notebook fragments, aphorisms and letters, are marked by a sense of a vanished religious authority. Many of his fictions, as Benjamin noted, are similar to parables: they seem to have a code, pointing to some meaning hidden to the reader. Alas, they are not truly allegorical – there is no Truth behind the fable. If Kafka’s work, as Scholem argues in his correspondence with Benjamin, ‘belongs to the genealogy of Jewish mysticism’, if, like that mysticism, it seeks to present a revelation, it is a revelation of the impossibility of revelation, an allegory of the absence of Truth.

Kafka’s life was marked by a faith in his vocation as a writer and a perpetual disappointment with the fruits of that vocation. He has been held up by many critics as a model of writerly integrity and an exemplar of the modern predicament of living in the wake of settled traditions.

W. and Lars immensely admire Kafka’s work. W. describes his life as having been marked by a sense of falling short of Kafka, which, given Kafka’s own sense of consistently fallen short of his own vocation – indeed, falling short because of that vocation – is a double banishment. W. has even attempted, but without success, to write literature in imitation of Kafka.

Kant, Immanuel, 1724-1804

Enlightenment philosopher, mentioned in Spurious solely for his condemnation of Schwärmerei.

L is for …

Lars

Narrator of Spurious, Lars lives in a damp-ridden flat in Newcastle. He is a friend and collaborator of W., who he visits in his hometown of Plymouth, as well as travelling with him to Freiburg and Dundee, among other places, to attend academic conferences and give presentations.

What we know of Lars is almost entirely refracted through W., conversations with whom, as recorded by Lars, form the substance of Spurious. He is, we can presume, employed in some kind of academic job, probably as a lecturer in philosophy, has published at least two books (according to W., they’re very bad), and has a role in the college where W. teaches, at one point inspecting W.’s teaching. He is also prone to making desperate bids to escape from his current position, attempting and failing over the years to become a scholar of Hinduism and of music. W. notes that because Lars has suffered periods of unemployment, he is ingratiating towards authority.

Like W., Lars cannot drive and has a penchant for flowery shirts. Lars is a Hindu by origin, but is, like W., an atheist.

For W., Lars is characterised by idiocy, obesity, over-exercised thighs and arms, continual illness, apocalypticism, administrative facility, emotional reticence, an inability to converse, Schwärmerei, whining, a sense of persecution, a victim mentality and general hysteria.

Leibniz, Gottfried, 1646-1716

Philosopher mentioned briefly in connection with Cohen, presumably since Leibniz invented the infinitesimal calculus so important to the Jewish thinker.

Levinas, Emmanuel, 1906-1995

Lithuanian born philosopher who spent his working life in France. Levinas is best known for his account of the relational genesis of the self. It is in our address to the presence of the other person, he argues, that we awaken to ourselves as individuals. In speaking to the other human, we become properly ethical. Levinas is distinctive in attempting to provide a phenomenological justification for this claim, and giving a new twist to what W. calls the logic of relations.

Leaders

W. and Lars have decided that their true role is to promote and serve the thought of others. This might in some measure redeem their own idiocy.

W. and Lars have picked out three leaders over the years, each of whom refused to accept that role. The first was characterised by his seriousness. The second was a man of faith and an expert in financial matters, who predicted economic collapse within the next few years. The third, apparently the greatest of them all, spoke with such profundity that he almost convinced W. and Lars that they could think.

The spiritual leader of W. and Lars is Kafka. They would like Tarr to lead them, too, if they could persuade him, which is unlikely.

Leper Messiah

The Talmud reports a conversation between Rabbi Joshua ben Levi and the prophet Elijah. ‘When will the Messiah come, and by what sign may I recognise him?’, asks the rabbi. Elijah tells the rabbi is already here, sitting among the poor lepers at the gates of the city. The Messiah binds his sores one by one, instead of bandaging them all at once, Elijah says, because he might be needed urgently, at any time.

Literature

The downfall of both W. and Lars, they agree, is that their literary enthusiasm has compromised their philosophical investigations. Reading Kafka’s The Castle set both of them off on the wrong path, W. spending years attempting to imitate Kafka in his own literary writing before giving up, and Lars, according to W., still thinking that he might be Kafka.

Logic of Relations, The

A synonym for the interhuman relation as explored in the German Jewish tradition exemplified by Rosenzweig and Scholem, as well as by Levinas and Blanchot.

M is for …

Man bag

Form of receptacle that W. finds vastly superior to the rucksack, which Lars favours. W.’s man bag is the perfect home for his notebook, he claims, and for his wipes.

Martini

Cocktail made with gin and vermouth, and garnished with an olive or lemon rind. W. and Lars find the Martinis at the members-only cocktail bar at the Plymouth Gin distillery to be particularly noteworthy.

Mathematics

Under the influence of Cohen and Rosenzweig, W. wonders whether mathematics might be the royal road to God. W. is a poor student of mathematics, however, having tried and failed to understand the infinitesimal calculus.

Mascolo, Dionys 1916-1997

Political activist and philosopher. Mascolo is best known now as a member of the Rue Saint-Benoit group, which gathered informally at the flat of Marguerite Duras. Mascolo met Duras, Bataille, Blanchot and others through his job as a reader for the French publishers, Gallimard.

Mascolo joined Duras in the Resistance in 1943, and followed her into the French Communist Party a few years later, before leaving it in 1949 with the aim of developing another institutional form for the left. With Blanchot, he drafted the so-called ‘Manifesto of 121’, and was also active in the Students and Writers Committee during the Events of May 1968.

W. sends Lars a quotation from Mascolo’s book, Communism, which reflects many of the views of the friends who gathered at Rue Saint-Benoit.

The Messiah/ Messianism

A restorative figure found in the Bible. Biblical prophets look forward to his coming, which will transform the world, punishing the sinful and rewarding the righteous. The figure of the Messiah gains particular importance in times of instability and persecution. It is also possible to speak of messianism, which is not simply a belief in a coming Messiah, but the sense that a new epoch is approaching.

Cohen gives the notion of the Messiah a new significance in his work, arguing that prophetic messianism names the defeat of injustice in the movement of humanity as a whole towards the realisation of universal ethical laws. The thinkers who followed him, Rosenzweig and Scholem among them, had, by contrast, lost their faith in such a movement. For them, messianism would intervene, if it did, by interrupting history, by showing that official history, the linear account of events, contains within it a utopian promise.

It is the relation to this messianism, this source of hope, to which Rosenzweig and Scholem, and thinkers who emerge from the same tradition (Levinas, and to some extent, Blanchot), link their reflections on ethics, politics and religion. They share a common sense that messianism is associated with the capacity to speak, to dialogue between human beings. For W., likewise, conversation can be said to be messianic, if approached in the right way.

In Spurious, W. and Lars are researching the topic of messianism with the aim of writing two parallel essays on the topic. They discuss the apostate Messiah, Sabbatai Zevi, as well as the story of the Leper Messiah, and consider the doubling of the figure of the Messiah that Scholem writes about, which sees the Messiah of the old world duplicated by the Messiah of the new one. Their reflections are animated by a vivid sense of what W. calls the logic of relations.

Moksha

Liberation from the cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth (reincarnation) in Hinduism. Through moksha, the soul attains ultimate peace and enlightenment in the union with God. It is only through moksha, W. says, that Lars will really accept the damp spreading through his flat.

Moment of Illumination

Rare event when Lars actually has an idea, according to W. Sometimes they involve using terminology from ancient Greek. W. mentions two moments of illumination in Spurious: once in a pub garden in Oxford, and another time on the long pier at Mount Batten.

Mount Batten

Outcrop of rock in Plymouth Sound, on which Mount Batten Tower, a circular artillery fort, was built. Mount Batten is a gateway to Turnchapel and other parts of the coast. Reachable from Plymouth by water taxi, it was the site of one of Lars’s moments of illumination.

Mount Edgcumbe

Country house and extensive grounds, bequeathed to the city of Plymouth by the Duke of Edgcumbe. Reachable by ferry, it is a favourite haunt of W. and Lars.

N is for …

Newcastle upon Tyne

City in the northeast of England, on the north bank of the river Tyne. Newcastle played a major role in the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, and was a major coal mining and shipbuilding area until the 1980s. Subsequently, the city was marked by poverty and unemployment. Newcastle saw concerted regeneration in the late 1990s and 2000s.

Lars lives in Newcastle, a city he and W. greatly admire not least because it, like Plymouth, is on the periphery.

Notebooks

Both W. and Lars have notebooks, W. following the advice of a friend, to write about the ideas of others using black ink, and, at the back, to develop his own ideas using red ink. Lars, according to W., fills his notebook with pictures of cocks and monkey butlers.

O is for …

Overpraise

Only hyperbolic praise can help one’s friends survive the Stalinist control procedures imported into British academia from business. Without it, as in Stalin’s USSR, there’s always the risk that ‘somebody’s going to be shot’.

Omoi

Classical Greek word meaning alas. The only word of ancient Greek that Lars learned from his studies, according to W.

P is for …

Puerility

Childishness, immaturity, triviality. Defining characteristic of W.’s and Lars’s sense of humour, which they’ve always regretted.

Philosophy

Branch of investigation that deals with questions concerning the nature of reality and the source of values. Most of the intellectual figures W. and Lars refer to in Spurious are philosophers, and we can deduce that they are employed in some capacity to teach philosophy. It also seems evident that W.’s and Lars’s route into philosophy was through Kafka, and therefore through literature. Indeed, both W. and Lars blame their inability to philosophise on the baleful influence of literature, and wonder what they might have become if they had a background in mathematics.

As they tell Sal, W. and Lars regard as impossible coming up with their own original philosophy, presumably given their idiocy. Nevertheless, they both rise early each morning to read and write philosophy, and W. in particular thinks he might be on the brink of having a philosophical idea.

Plymouth

City in the southwest of England, magnificently located on the stretch of coastline called the Sound, between the mouths of the river Plym and the Tamar. The Hoe, the public space running along much of the Sound, gives a splendid view of what is the largest natural harbour in the country.

Like the equally peripheral Newcastle, Plymouth is a poor city, which condition the imminent departure of the Royal Navy will only exacerbate.

Plymouth Gin

Gin distilled at the Black Friars Distillery in Plymouth, formerly a monastery of the Dominican Order. With corporate buyouts in the 2000s, Plymouth Gin was relaunched as a brand, and its bottle redesigned. Gone, sadly, is the depiction on the inside of the label of a monastery friar, whose pictured feet, it was said, should never run dry.

Plymouth Gin is best in enjoyed with water, rather than tonic, and should be sipped from a wine glass for full appreciation of its bouquet.

Poland

W. and Lars recall a visit to Poland, which took place before the events recorded in Spurious. They journeyed from Warsaw to Wroclaw in the company of a guide, and claimed to have learnt a great deal from the steadily paced drinking of the Poles.

R is for

Ringlets

Locks of hair hanging in corkscrew-like curls, as worn by Orthodox Jews. W. is cultivating his ringlets, which, he claims, are particularly disliked by drivers.

Franz Rosenzweig, 1889-1929

Great German Jewish thinker, known for developing what he called the ‘new thinking’, which combines philosophy and theology. Unlike what he calls the ‘old thinking’ of previous philosophy, which placed emphasis on an abstract, atemporal attempt to grasp reality, Rosenzweig takes up the insights of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche in order to understand what is particular to individual human existence in its relation to God. In their correspondence, he and his friend Rosenstock co-develop an argument as to the significance of speech in human moral life, claiming that the moral self awakens in its address to the other person in speech.

The Star of Redemption, his masterpiece, was written in a six month burst of creativity whilst Rosenzweig was in military service during World War I. Upon his return to civilian life, Rosenzweig founded a well-known centre for Jewish adult education in Frankfurt, the Lehrhaus, which attracted Kafka, among other German-Jewish intellectuals, through its doors. Shortly afterwards, Rosenzweig was diagnosed with a progressive paralysing illness which soon saw him completely ‘locked in’. In the years that remained to him, Rosenzweig was, through a method of ‘dictation’, able to keep up a prolific correspondence and translate the Hebrew Bible in collaboration with Buber.

Eugen Rosenstock (later, Rosenstock-Huessy), 1888-1973

German born philosopher and sociologist, known to posterity chiefly as a friend and correspondent of Rosenzweig, who he influenced with his idea of ‘speech-thinking’. Rosenstock argued for the importance of speech as a responsive and creative act, claiming, in particular, that theoretical thought has thus far failed to attend to the significance of the vocative case in speech, in which the self is summoned or called by the other person. He thus replaces Descartes motto Cogito, ergo sum, I think therefore I am, which grounds the experience of the world in the thinking subject with the motto ‘Respondeo etsi mutabor’—‘I respond although I will be changed’.

As has been revealed in recently published correspondence, Rosenzweig fell in love with Rosenstock’s wife, Margit Heussy, or Gritli. This love was reciprocated with Rosenstock’s knowledge, and inspired the central notion of revelation in The Star of Redemption.

S is for …

Sal

W.’s partner and inspiration. A talented worker with glass, she has practical skills, which W. and Lars entirely lack. Sal wonders why W. and Lars haven’t developed their own philosophy, and finds their work, when presented, to be vague and boring.

Sansrkit

Ancient language of the Indian subcontinent, with a status analogous to that of Latin or ancient Greek in Europe, being of only scholarly interest outside its use in religious liturgy. According to W., Lars tried and failed to learn Sanskrit as part of his study of Hinduism.

Schelling, F. W. J., 1775-1854

German idealist philosopher mentioned in passing in Spurious, whose unfinished Ages of the World was a particularly important influence on Rosenzweig.

Scholem, Gershom 1897-1982

Philosopher and scholar of Judaism, known for his writings on Jewish mysticism, messianism and Sabbatai Zevi. Scholem was one of several thinkers who sought to rethink the relationship to Jewish tradition in the wake of the World War I. He placed particular emphasis on the tradition of philosophical commentary on Jewish sacred texts and ideas. The story that Scholem tells in Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, which is paraphrased in Spurious, was originally from a Hasidic lesson told by Agnon.

Schwärmerei

Literally meaning to swarm, it is used in German to mean something similar to enthusiasm, exaltation or fanaticism. In a late essay, Kant characterises as Schwärmerei all attempts to access an immediate knowledge of the supersensible. For him, all such claims of direct knowledge – of ‘supernatural communication’ or ‘mystical illumination’ – entail ‘the death of all philosophy’ since the knowledge being claimed is not demonstrable to others.

Southwest, The

Region of England, encompassing the counties of Devon and Cornwall. The southwest is particularly admired for its natural beauty and warm, sunny climate.

Spinoza, Baruch, 1632-1677

Rationalist philosopher, famed for his claim that nature is an indivisible, uncaused substantial whole identical to God. For Spinoza, talk of God’s purposes, intentions, aims or goals is anthropomorphising; rather, everything which exists is brought into being with necessity by nature. In his masterpiece, the Ethics, Spinoza argues that human happiness depends upon the life of reason, as distinct from the ephemeral goods we normally pursue. Our main good, Spinoza argues, is the difficult to attain knowledge of God – of nature in its entirety. It is this knowledge which allows us to experience part of the infinite love that God/nature has for itself: in short, beatitude.

Spurious

Spurious is a novel, presenting the conversations and adventures of W. and Lars had over the course of two years. It would seem that the book derives from conversations that Lars has recorded and put on his blog. Some of these conversations are fictional, W. protests: he claims not to recognise himself in everything Lars has written.

It is also a name of a weblog, on which W. and Lars were introduced. http://spurious.typepad.com/

Strasbourg

French city on the borders of Germany, and home to the university where Levinas and Blanchot studied in the 1920s.

Syriac Book of Baruch, The

Apocryphal apocalyptic text written in the decades following the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Baruch is a scribe in the Book of Jeremiah, but is here promoted to prophet. Like Jeremiah, he is subject to various visions concerning the apocalypse and the coming of the Messiah.

T is for …

Talmud, The

A compilation of rabbinical discussions concerning the Jewish law, ethics and other topics forming the basis of religious authority in Orthodox Judaism. W. sends Lars two quotations from the Talmud, the first of which looks forward to the restoration of the Kingdom of the House of David, that is, the coming of the Messiah.

The second quotation reflects the despair that followed the Roman persecution of the Jews after the second destruction of the temple. The claim that ‘those that emit semen to no purpose delay the Messiah’ might seem a surprising one, but was directed against contemporary practices. Rather than bringing children into a corrupt world, men masturbated, or took wives too young to have children. For the rabbis, who believed that all souls are stored in heaven since the beginning of the creation, waiting only to be born, such practices only prevented the coming of the Messiah.

Béla Tarr, 1955-

Hungarian film director, whose work is characterised by a narrative slowness, bleakness of vision and apocalyptic sensibility that reflects their source material, the novels of Tarr’s close friend and collaborator, Krasznahorkai. Tarr, unlike Tarkovsky, refuses to give any sense of religious redemption in his films.

Tarr’s productions are notoriously disaster prone. He has said that his latest film, currently shooting in Budapest, will be his last. Tarr is an extraordinary interviewee, seeming to have stepped directly from one of his own films.

Playing Tarr’s films to his students comprises a great deal of W.’s teaching. He particularly admires the director for his devotion to the concrete, which is quite the opposite of W.’s and Lars’s windy enthusiasm for lofty philosophical ideas.

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1932-1986

Spurious alludes to Nostalghia, Tarkovsky’s bleakest film, which sees the madman Domenico, played by Erland Josephson, set himself on fire in a public square in Rome as a warning to humanity.

Titisee

Resort in the Black Forest, close to Freiburg, where W. and Lars hire a pedallo to go out onto the lake.

Tohu vavohu

Hebrew phrase, used in the Books of Genesis and Jeremiah. It is translated in the King James Bible as ‘without form or void’ and has the general sense of chaos and disorder. This phrase can be found on the cover of Godspeed You Black Emperor!’s 1999 mini-album, Slow Riot for New Zerø Kanada.

Turnchapel

Village in the southwest of England, for which Lars has a special love. It is reachable from Plymouth Barbican by water taxi.

V is for …

Vortex of Impotence, The

Phrase used in a quotation W. sends Lars. It’s from one of the essays in Virno and Hardt’s collection Radical Thought in Italy.

W. is for …

W.

Central character in Spurious, W. lives in a large, damp-free townhouse in a deprived part of Plymouth. He is a friend and collaborator of Lars, who he visits frequently, and has a teaching role in a college, probably in philosophy, though perhaps in theology (or, indeed, a mixture of both). He is a Hebrew scholar, and has recently published a book.

W. spent several of his childhood years in Canada, before returning to the prosaic city of Wolverhampton, where he attended a grammar school. It is not clear from Spurious when or where he met Lars, but W. thinks of his friend as a protégé.

A great deal was expected of him as a thinker in his early days, W. reports, but his sense of the apocalypse, as well as his enthusiasm for drinking and smoking, have prevented him from reaching his potential. The presence of Lars in his life has only made things worse, he says.

W.’s partner is Sal, who he loves and admires.

W.’s hair is long, with ringlets. He is of Jewish origin, though his family were Catholic converts. He is an enthusiastic reader of the work of Cohen, Rosenzweig and Spinoza, and admires Tarr’s films. He keeps Lars up to date with his research by emailing quotations to him.

W. characterises himself as having great generosity as a host, a love of conversation and a feeling for the messianic, as well as a general enthusiasm for rivers, the sea and the Southwest. He credits himself with a higher IQ than Lars, and is a reluctant atheist. W. is frustrated by his mathematical and linguistic inability.

W. dreams of returning to Canada, and of having a genuine philosophical idea. He is a great believer in friendship and an advocate of overpraise. Despite their many professions of gloom, he and Lars are essentially joyful people, W. believes.

Wipes

Disposable tissue for wiping clean one’s hand or anything small, which W. and Lars use to dab their wrists and behind their ears before giving a presentation.

Wolverhampton

City in the West Midlands, to which W. returned with his family after a few years in Canada.

X is for …

Mill on the Exe

W. and Lars drink at the pub called Mill on the Exe in Exeter, where they reflect on the splendour of the Southwest and the threat it poses to serious philosophical work.

Y is for …

Yard, the

Lars’s backyard particularly depresses W. It is a concrete patch behind Lars’s flat, shared with the flat above and filled, according to W., with rats, sewage, bin bags and rotting plants. W. suggests that only Béla Tarr would have interest in such a place, allowing it to tell its story in one of his famous tracking shots.

Z is for …

Sabbati Zevi, 1626-1676

Self-proclaimed Messiah who, although treated with suspicion by religious authorities, was able to attract a large following in Turkey and elsewhere in Europe. Zevi was known for his ‘holy sins’, which began early on with his eating of non-kosher food, and speaking the forbidden name of God, and, later led him to pronounce the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew, an act forbidden to all but the Jewish high priest on the Day of Atonement. Zevi’s conversion to Islam in 1666 was viewed as a betrayal by most of his followers, but by others as a sign of his messianism; many followed him. W. mentions Zevi’s apostasy as the outcome of a tradition in messianic thought that holds that the Messiah breaks the law rather than merely fulfilling it.

Barnes and Noble Review: Guest Books (2012)

1. Henry Green, Concluding

My favourite books are curates’ eggs, one-offs that are utterly unthinkable without their very particular author. Such a book is Henry Green’s peculiar and beautiful and ironically titled Concluding, set in alternative present during a single day at a girls’ boarding school, after two pupils have disappeared. What happened to them is never revealed, even when one of them is found, but it seems that they sought to escape the strictures of their education at the hands of the sinister State. Nor do we learn of the outcome of the struggle between the State-aligned governesses, Miss Edge and Miss Baker, and the retired scientist, Mr Rock, whose presence in the school grounds they find so irksome. These, and other unresolved plotlines, are really only the occasion for the beguiling meanderings of Green’s novel, which pitches against bureaucratic conformism not only Rock’s old-world commonsense, but also the pagan energies of the girls. I love Concluding for the glorious, syntax-straining sentences that flare out of nowhere, and are full of those same wild

energies.

2. Denton Welch, A Voice Through A Cloud

Denton Welch, like Henry Green, has a small, but devoted following, and his life is as fascinating as his work. Welch began to write after a terrible accident as an art student, when his bike was hit by a car. His third novel, A Voice Through A Cloud, left unfinished when he died of his injuries at the age of thirty-three, recalls Welch’s accident and rehabilitation, and showcases the powers of precise description that are so evident elsewhere in his writing. Perhaps it is the subject matter of the novel which makes it so moving, but there is also something deeply affecting in Welch’s delicate tracing of the psychic tropisms of a young patient, invalided at a time when his life should have taken flight, lonely for companionship, struggling with his dependency on stern and businesslike nurses, and fascinated by the seductive figures of his doctors, who, sympathetic and interesting, are too busy with their work and their lives to give him the companionship he craves.

3 Robert Walser, Jakob Von Gunten My third choice is also a ‘little’ book, by that author most enamoured of the small and the unobtrusive: Robert Walser. His third novel takes the form of a diary recording the impressions of a runaway, Jakob, enrolled at the Benjamenta Institute, which trains its young charges as servants. Like so many other of Walser’s characters, Jakob actively seeks obscurity, wanting nothing more than to lead his life as a ‘zero’. Happily bent on that course, he enjoys speculating about the eccentric Benjamentas, the brother and sister who run the Institute, as well as about the secrets which might lie within the institute’s mysterious ‘inner chambers’. The charm of this novel, which brings together folk tale and Bildungsroman even as it echoes with contemporaneous novels of introspection, is unparalleled in Walser’s oeuvre. Particularly admirable is the fussless way in which Walser leads us into his strange world, his unornate language as direct as Kafka’s, a good counterpoint to the strength of his vision – so confident in its oddness; so unique.

From Literary Hub, 2019

Five Great Books About Visionary Youth

LARS IYER, THE AUTHOR OF NIETZSCHE AND THE BURBS, SHARES FIVE BOOKS IN HIS LIFE

Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz

(Yale University Press, 2012, originally published, Poland, 1937)

Witold Gombrowicz’s mapcap novel Ferdydurke is a celebration of immaturity, mocking convention, propriety, officialdom and high culture. However, this is no straightforward hymn to youth—the protagonist, magically turned from a thirty-year-old writer into a teenage schoolboy—suffers all kinds of humiliations. Still, it’s clear where Gombrowicz’s sympathies lie. Ferdydurke depicts the anarchy of youth—its wildness, its impatience—but it also exposes the anarchism at the base of our schools, our families, and of middle-class life. All authority, Gombrowicz’s novel declares, is usurped. Chaos reigns.

Jane Ciabattari: Why was Ferdydurke banned in Poland for many years after its publication in 1937? What’s so dangerous about its depiction of youth’s anarchy?

Lars Iyer: In a word, ludism. Youth’s queer anarchy, in the rolling riot of Ferdydurke, is the opposite of self-solemnity, of the ponderous weight of adulthood, of the staidness of the old order, of the old monosexualities, just as it laughs at the new order, too: at the new avatars of the Modern, of the Young Girl (a figure later borrowed by the Tiqqun collective) and her right-thinking family. The spirit of youth, of humor, serves no ideological certitude, thumbing its nose at the Nazi-occupiers of Poland and the communists who succeeded them.

Hamlet is perhaps not technically a teen (we never learn his exact age—only that he is a student), but I think it’s inevitable that we read him as such—as a doomed adolescent, caught in the Limbo before adulthood in which he lacks a role in the world, a capacity to act. The older generation are either corrupt—his mother has married his father’s murderer, arousing his disgust of the body, of sexuality—or suffocatingly conventional; whence his particular contempt for the all-too-sensible blandishments of Polonius, the advocate of normalcy. The larkishness of his university friends can offer no cheer, and he cannot reciprocate Ophelia’s love. Hamlet’s melancholy leads in one direction. His prevarication, his mixture of juvenile caprice and adult seriousness, finds its fitting resolution in the nihilistic tableau of the final act, with dead bodies littering the stage.

JC: What might be the signature lines from Hamlet that most resemble the nihilistic themes in your new novel?

LI: The first soliloquy has so much:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter! O God! God! How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable, Seem to me all the uses of this world! Fie on’t! ah fie! ’tis an unweeded garden, That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely.

Life as “rank,” “gross,” as an “unweeded” garden that has run wild, full of disgusting things. Better not to exist at all than to be part of chaos and corruption. My central cast of characters, never as depressed as Hamlet, although they might to think of themselves as so, run up against the old problem of the meaning of suffering. They’re tempted simply to lay down their arms, to give in. But they’re too alive for that, asking instead how they might impose meaning and order on a dead world—to cultivate their figurative garden in the middle of the suburbs. Nietzsche, their new schoolmate, advises them to drop their pity and self-pity, prizing suffering for the chance of genius that might spring from it. They, in turn, become convinced of Nietzsche’s genius, persuading him to become the frontman for their band…

Yukio Mishima is the laureate of fanatical youth. The Sea of Fertility, a novel tetralogy, is about a transmigrated soul, reincarnated at four moments in southeast Asia in the twentieth century. The second novel of the tetralogy, Runaway Horses, set in the early 1930s, depicts a samurai-inspired group of young ultra-nationalists who aim to attack members of the country’s financial elite. The group falls apart. Yet Isao, the reincarnated soul, acts alone, assassinating his target, and then, satisfied that he’s fulfilled the central purpose of his life, commits seppuku, ritual disembowelment, before the rising sun. Has anyone but Mishima conveyed the desire for death, for cleansing self-sacrifice, visible in young men?

JC: Mishima certainly captured a sense of nihilism in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. And he proved his own commitment by his suicide shortly thereafter; his ritual seppuku mirrored that of Isao and overshadowed his final work. Why do you think the novelist and the man converged in this way?

LI: Mishima’s own terrorist action took place on the same day he completed his tetralogy, storming the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defence Forces, with his private army of adolescents, and taking his life in the samurai style. He sought to turn himself thereby in a glorious object, hoping to inspire the coup that would restore the power of the Emperor. The obvious futility of the action did not concern him, indeed, it made it only shine the more brightly.

Curious, then, that the fourth volume of The Sea of Fertility, set in the Japan of the 1970s, presents a far more farcical suicide. Torū, the protagonist of The Decay of the Angel, is psychologically poisoned by his guardian’s cynicism and disgust. His botched suicide leaves him blind and bitter, living on beyond the age in life at which his previous incarnations died. Did he miss his appointment with destiny—or was there no such thing as destiny in the first place?

Completing the truncated, malformed, blackly cynical The Decay of the Angel on the day of his seppuku, Mishima provides an ironic commentary upon his own action.

Tiqqun’s provocative work of “trash theory” presents us with The Young Girl—a figure of both the ultimate consumer and the ultimate worker of contemporary capitalism. She’s frivolous about the important issues—the climate crisis, total financialization and commodification—but serious about frivolous ones: the advancement of her career, getting ahead on social media—OMGing and LOLing, tweeting and posting and linking and liking. Why is this figure female? Because of the widely remarked upon feminization of labor in the workplace, and, increasingly, outside of it, which have seen a new emphasis on social skills and emotional work. The Young Girl does not refer to women per se, but to the prematurely cynical shock troops of our financialized hellworld, which, what with looming climatic and financial catastrophe, might not last very long.

JC: You’re drawing a direct line to Tiqqun’s work in your new novel, creating a character, Nietzsche’s sister, who is a Young Girl. How does she go about recruiting other Young Girls?

LI: Nietzsche’s unnamed sister in my novel is a “futurist,” advising companies how to adapt themselves to current trends. She also founds the FailBetter Recruitment Agency and visits the sixth-form of my novel to spread the word. A current business trend has firms encouraging the anti-corporatism of its potential Millennial and Generation Z employees. Efforts at “internal marketing” see firms promoting work for charity, with feed-the-homeless days, as well as virtue-signaling green initiatives, to make their workers feel part of a meaningful enterprise. It’s a continuation, in many ways, of the playful workplaces of the Dotcoms, aimed to encourage staff loyalty. Nietzsche’s sister is very much part of a world of entrepreneurial rhetoric that looks increasingly threadbare in the face of the climate crisis and looming financial collapse.

Exodus reviewed in Literateur by Nikolai Duffy (2013)

Nikolai Duffy

Exodus: the second book of the Old Testament, which recounts the departure of the Israelites out of Egypt; shemot (‘names’) in the Pentateuch; literally a ‘going out’: ex, meaning ‘out’, and hodos, way. Also, from the Greek, exodus, ‘a military expedition; a solemn procession; departure; death.’

***

In a short essay on Derrida’s notion of différance, translated as ‘Elliptical Sense,’ Jean-Luc Nancy invokes the phrase ‘the lightening of meaning’ which, Nancy writes, refers to the ‘knowledge of a condition of possibility that gives nothing to know.’ In such a situation, he suggests, ‘meaning lightens itself […] as meaning, at the cutting edge of its appeal and its repeated demand for meaning.’ [1]

***

Exodus is the third instalment of Lars Iyer’s much celebrated trilogy (after Spurious, 2011,and Dogma, 2012) cataloguing the existential, professional, political, and economic ruination of Lars, W., philosophy, universities, academia, life, and everything else. Lars and W. are a classic double act: acerbic, perplexed, frustrated, bound. And they are extremely funny, tragically funny. Think Beckett, think Laurel and Hardy, Little and Large. Across the wastes of Britain, academia, one playing off the other, each reprising roles laid out before any of this began, sticking to them, by and large, for lack of any clear sense of any other way to behave. This is the stuff of intimacy: W.’s abuse of Lars; Lars’ acquiescence. Lars: the half-Danish, half-Indian, used to work in a warehouse; W., the academic with great leanings towards what he describes as ‘the majesty of thinking’, contemplation, the big questions, and who claims Irish and Jewish heritage.

***

‘Critical discourse has this peculiar characteristic: the more it exerts, develops, and establishes itself, the more it must obliterate itself; in the end it disintegrates. Not only does it not impose itself – attentive to not taking the place of its object of discussion – it only concludes and fulfils its purpose when it drifts into transparency.’ [2]

***

This time, Lars and W. go on one last lecture tour of Britain to assess the ‘ruins of the humanities’ and the conditions for W.’s sacking.

Not much happens. They come and go; they drink gin; they talk, a lot, not necessarily about anything in particular. They have a sense of the ridiculous. They go on and on, relentlessly.

***

Surfaces can be difficult to read and the slate is never wiped clean, really, no matter the scourer used. Lines of reference are tangled, an entire condensed pattern of connection. Driven to entertainment.Besides, it is not always easy to be what one says; matter lost in grammar and convention, and convergence, too, the edge of letting go.

To move in the spaces language opens.

A place where life and writing come together; an engagement with history, ground, that is also a way of thinking the rifts of life, its relative strangeness, the stuff of things, some of it choppier than the rest; a whole made up of pieces, fragments: the gaps, the inconsistencies, the blindsights. Most often, contradictions are restless and ambiguity pulls in more than one direction.

***

Lars and W. are great refuseniks, even of refusing. Idealism figures as cynicism; certainty is a fine example of irony; and thinking about what irony might mean is just another reason for apathy.

And no wonder: as Paul de Man comments in ‘The Rhetoric of Temporality,’ irony is duplicitous and undecidable; it doesn’t say what it says, but neither then does it say what it doesn’t say, such that the duplicity of irony necessarily also extends to any discourse on irony.

‘Curiously enough,’ de Man writes, ‘it seems to be only in describing a mode of language which does not mean what it says that one can actually say what one means.’ [3] The ‘not-itself’ of irony does not mean that irony is negative but simply that irony establishes a way of speaking that undoes what is said.

***

‘The moment’s come, W. says on the phone. They’re closing the philosophy department at Middlesex.

W. imagines them like giant crabs, the destroyers of philosophy. As giant crabs with great metallic claws. But in the end, they’ll only be managers. Manager-murderers, with profit-and-loss spreadsheets.

‘It’ll be our turn next,’ W. says. ‘They’re coming to get us.’ The cursor, on someone’s monitor, is already hovering over our names.’ [4]

***

In The Writing of the Disaster Maurice Blanchot, about whom Iyer has written two books, writes that the grand irony is apathy: ‘not Socratic, not feigned ignorance – but saturation by impropriety (when nothing whatsoever suits anymore), the grand dissimulation where all is said, all is said again and finally silenced.’ [5]