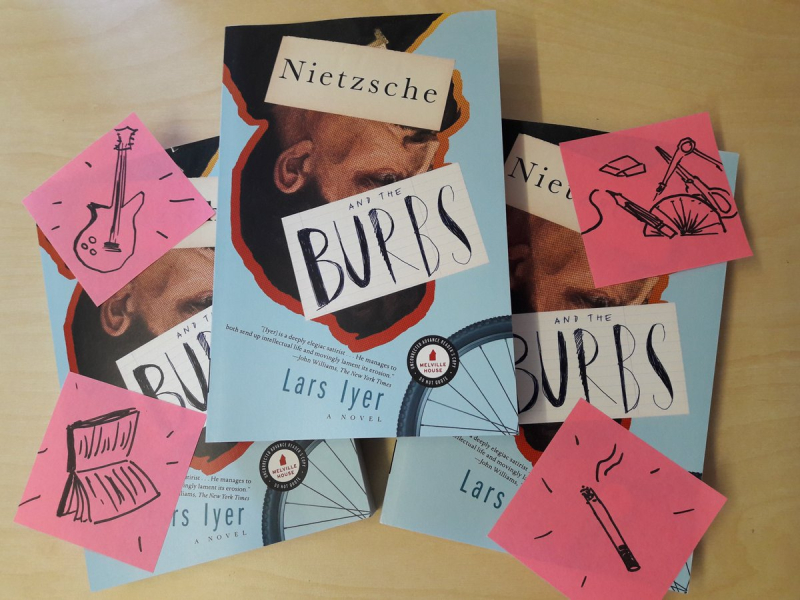

'Nietzsche and the Burbs is an anthem for young misfits and a hilarious, triumphant book about friendship'. Michael Schaub reviews Nietzsche and the Burbs at NPR.

Author: Lars Iyer

Steve Mitchelmore reviews Nietzsche and the Burbs at This Space.

New interview at Bookmarks at The Literary Hub, based on five books I've chosen that on the topic of visionary youth.

Nietzsche and the Burbs featured in Vol. 1 Brooklyn December preview.

And in the Chicago Review of Books books to read this December.

Michael M Grynbaum reviews Nietzsche and the Burbs for the New York Times.

A clique of misfit teenagers in suburban England sit on adulthood’s cusp, lamenting their middle-class lives and fretting for their futures. Enter a new boy, a stranger booted from a posh academy, who scrawls “NIHILISM” on the cover of his notebook and elevates the group’s ennui into something more profound. They call him Nietzsche, as in Friedrich. We never learn his real name.

Not much happens in “Nietzsche and the Burbs,” a peculiar new novel by Lars Iyer. The final 10 weeks of high school go by. There are house parties and bicycle rides and exams. Only one member of the group, Chandra, serves as narrator, but the novel’s voice is a collective one: an angsty adolescent Greek chorus. “Who are we supposed to be?” it asks. “What are we supposed to want? Are we any different from the people we hate? Won’t we have to become like them in the end?”

It goes on like this. Nietzsche keeps a sad blog about the suburbs (“Nothing will happen, not today”). The group watches “Melancholia” and reads Dostoyevsky. Drugs are taken, and sex, very occasionally, is had. “Why are we so tired, at the peak of our lives?” the narrator asks. “Why are we falling asleep, at the peak of our lives?” Think “On the Genealogy of Morality” meets “The Breakfast Club.”

You may be unsurprised to learn that Iyer is a longtime lecturer in philosophy (he currently teaches creative writing at Newcastle University). His last novel, “Wittgenstein Jr.,” is a funhouse version of this one; it fictionalized the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein as a modern-day Cambridge professor, as seen through the eyes of his students. “Nietzsche and the Burbs” sticks to the same formula, illuminating and gently mocking the ideas of its title subject.

At 345 pages, “Nietzsche and the Burbs,” like any well-meaning professor, can belabor its point. The novel idles for long stretches, and there’s too much space between memorable sentences, like the one that compares an erection to a “narwhal’s tusk.” Characters blur together; only one, Paula, a jaded lesbian who falls in and out of love, stands out. The Nietzsche character remains a cipher until the end.

Scholarly readers — or those with access to the Wikipedia page for Continental philosophy — will find that in-jokes abound. Like Friedrich, Iyer’s Nietzsche has an overbearing sister, a father who died young and a crush on a girl named Lou. (The real Nietzsche pined for the writer Lou Salomé.) One imagines the faculty club guffaws when a character wonders, “Does being clever always make people miserable?”

But Iyer’s talent is best deployed in scenes that plumb the poignancy of finishing high school and leaving home — a moment when one’s world can be at once filled with kaleidoscopic possibility while also disintegrating. As he watches classmates frolic in an end-of-term field day, Chandra identifies the odd feeling of nostalgia for the present day: “A valedictory air. A last-of-the-last-days air. There’s not much school left. There’s not long to go. Days ringing out in the infinite. As though they will never pass. … As though these last, languorous days will last forever.”

This is a near-perfect evocation of childhood’s elegiac end. And it proves Iyer’s literary talents can occasionally match his philosophical ones.

Nietzsche and the Burbs reviewed by Jane Ciabattari at BBC Culture.

The charismatic new boy who has arrived at a suburban Wokingham high school from a private school fits in immediately with a crew of rebels who adopt him, protect him, and serve as the chorus to his journey through the last nine weeks before exams. They dub him Nietzsche, and cast him as lead singer in their metal band, the Burbs. His lyrics lead them: “The sky is hollow. The stars are blind.” They share drugs, alcohol, philosophical discussions, parties and cycling trips through the suburbs. (“There should be signs: Warning: Low Meaning Zone. Hazard: Nihilism.”) They support Nietzsche when he confides with them about his mental breakdown, and when he finds love. Iyer’s swiftly paced, gently satirical fifth novel builds to a startling crescendo.

Chicago Review of Books selects Nietzsche and the Burbs as one its books to read this December.

London launch of Nietzsche and the Burbs at the London Review Bookshop on January 28th, with Jon Day at 7PM. It's a ticketed event (buy them here) – they sold out before the day last time.

New review at Shelf Awareness:

Nietzsche and the Burbs by Lars Iyer (Melville House, $16.99 paperback, 352p., 9781612198125, January 9, 2019)

Lars Iyer (Wittgenstein Jr.) makes nihilist philosophy hip and fun in his highly entertaining tragicomedy Nietzsche and the Burbs.

The novel introduces a group of disaffected teenagers finishing their last year of secondary school before heading out into the big, uncaring world: Art, Merv, Paula and the narrator, Chandra. The foursome inducts into their clique a new student, whom they nickname Nietzsche due to his gloomy disposition and pessimistic outlook on life. They sense he is intellectually superior, perhaps braver, and thus look up to him as a kind of leader. The four get him to front their rock band, called Nietzsche and the Burbs, believing music can save them from the banality of life. For his part, Nietzsche plays in the band–though not as enthusiastically as his friends would like–and spends most of his time developing a philosophy of the suburbs, posting on his blog about his conclusions while participating in the parties and the general hullabaloo of high school.

Iyer writes in short, emphatic elliptical sentences, a little maddening in their repetition but effective in creating a mood of rebellious adolescence. The style works in portraying the young characters' molten thoughts and emotions, as well as in satirizing the suburbs and school life. The group lives and studies in a suburban English town aptly named Workingham, which comes to symbolize the "hangover of history," the final phase of humanity distinguished by a nauseating sameness. As much fun as Iyer has in hilariously sending up tract houses and golf courses, he's at his satirical best describing the social stratification in the school. It's not the jocks or the "beasts" that rule the day, but rather the "drudges," those complacent, phone-addicted students who seem to have succumbed entirely to first-world mediocrity.

There's something daring and poetic in the main characters' resistance to suburban culture. They take drugs, they read books, and they play music that defies categorization. In their nihilism, they talk about affirming their lives in a significant way, through art, through suffering. Iyer brings Nietzschean philosophy to heady, raucous life, fleshing out the ideas of nihilism and existentialism in ways that few books do. The characters don't just talk philosophy; they embody it in their decisions and actions. They test their surroundings with radical ideas. It's an exhilarating ride, evoking the grandiosity of youth and the dynamics of counterculture itself. Of course, there's a tragic arc to the story. Beneath every uproarious protest cry is something human and fallible, Iyer sharply reminds readers.

The brilliant, relentless drive of the narrative of Nietzsche and the Burbs demands a certain amount of stamina from readers. But the payoff is great. Perhaps not since Don DeLillo's White Noise has a novel so funnily and savagely lifted the veil on Western postmodern culture. What's underneath is hard to explain. Some may find darkness, others beauty. — Scott Neuffer

Here's the review from Booklist (hard copy only):

Nietzsche and the Burbs. By Lars Iyer Dec. 2019. 352p. Melville, paper, $16.99 (9781612198125)

Paula, Art, Merv, and Chandra—a coterie of sixth-formers in a British secondary school, would-be nihilists in training wheels. When they discover the new boy in school is himself a nihilist, a philosopher manqué, they quickly adopt him, dubbing him Nietzsche, inviting him to join their band as singer, and naming the band Nietzsche and the Burbs. Ah, the burbs, the focus of their sneering attention, their cynicism, their conviction that, though they might escape them temporarily, they will ultimately wind up back in their clutches. Their story, which takes place over the course of 10 weeks, is narrated by Chandra in a vaguely stream-of-consciousness voice replete with sentence fragments, omnipresent snippets of burbs philosophy, and extended conversation among the coterie. Nietzsche himself has little to say except for his pithy blog posts: e.g., “Perpetual imminence. Eventless events. Nothing happening except for this nothing is happening.” What is the book about? The kids’ quotidian school life, the occasional party, drinking, and Nietzsche—the real one, not the intriguing imitation. The limited action leads up to a denouement: an actual public performance by the band. Does it go well? Let’s just say readers won’t be surprised by the answer. How closely fictional Nietzsche is meant to resemble the real thing is moot except for the fact that the fictional one has gone off his meds. Uh-oh. Some readers may find the often-allusive book too clever by half; others will delight in its wit. In either case, the book is a model of originality. Clever, indeed. — Michael Cart

Publishers Weekly review Nietzsche and the Burbs:

In this devastatingly withering follow-up to 2014’s Wittgenstein Jr., Iyer turns his keen eye and sharp sense of humor to the suburbs. There’s a new boy in the London suburb of Wokingham, recently transferred from a posh private school after he lost his scholarship. He’s taken in by his new high school’s resident group of misfit creative types, who name him Nietzsche, after his pseudo-deep blog and the giant NIHILISM scrawled across his notebook. Though one of the misfits, Chandra, an Indian boy with creative writing ambitions, is technically the narrator, the novel is written from a plural first-person perspective that folds together Chandra’s voice with those of his friends, all of whom are deeply devoted to two things: their death metal band and cynicism. Nietzsche, then, is the perfect lead singer for a band that makes “the music that comes after music. Fucking ghost music, man.” Despite their cynicism and aversion to any platitudes, the nihilist heroes discover the sincere thrill of being young in high school, as they run through a gamut of heartbreaking, hilarious, and exhilarating experiences with love, drugs, and the immediate and terminal future. The individual characters tend to get lost in Iyer’s dense narration, and they are occasionally too clever for cleverness’s sake. But readers will be endeared by Iyer’s skillful portrayal of their deep tenderness and uncertainty despite it all, even if they’d hate for readers to know it. (Dec.)

First reviews for Nietzsche and the Burbs (due to be published in January 2020).

'A funny campus novel about despair… dark, brooding fun'. Kirkus Reviews

'Devastatingly withering'. Publishers Weekly

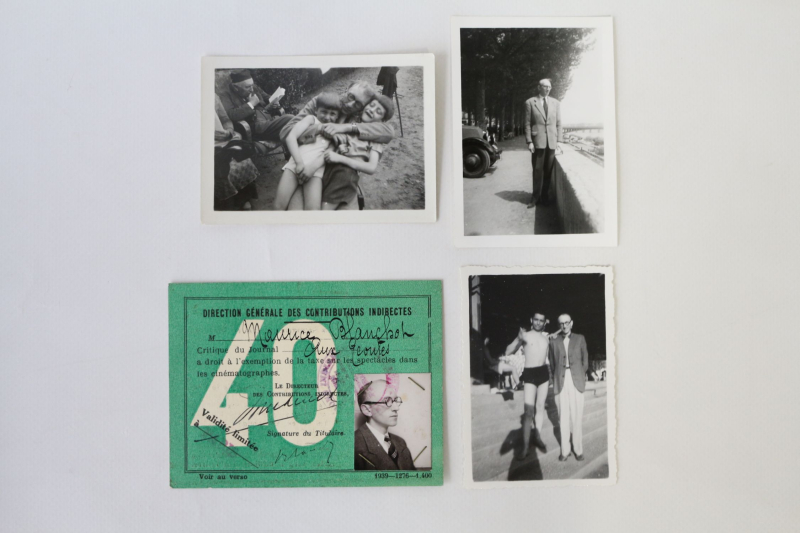

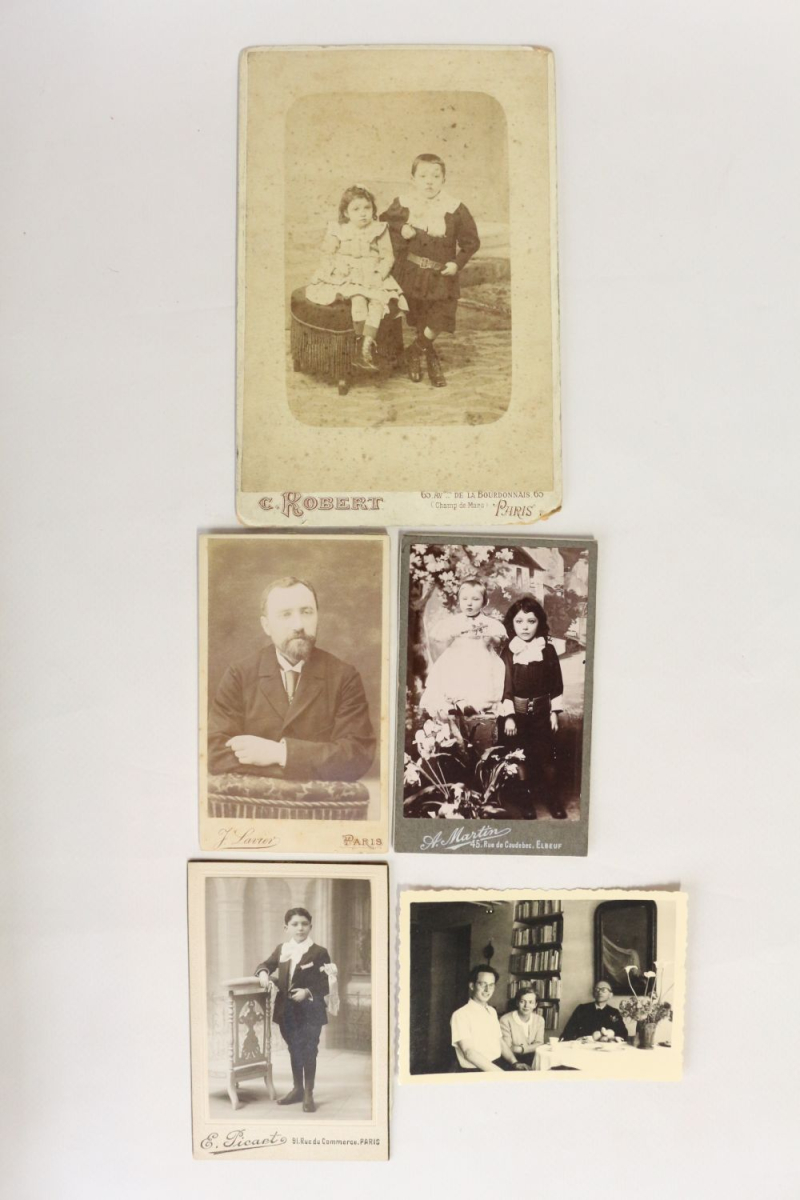

Documentation relating to the sale at auction of Blanchot's correspondence with his family.

Maurice Blanchot's complete correspondence with his mother, his sister Marguerite, his brother René and his niece Annick

1928-1991, various sizes, a collection comprising more than 1200 complete letters.

An exceptional set of more than 1200 autograph letters signed by Maurice Blanchot addressed mostly to his mother Marie, his sister Marguerite and his niece Annick, as well as a few to his brother René and his sister-in-law Anna. Some of Anna Blanchot's written parts have been excised, but the letters remain complete of Maurice Blanchot's writings. To the 1200 complete letters, we join a few incomplete additional letters, where some of Maurice Blanchot's text is missing. This collection was kept by Marguerite Blanchot with the books her brother inscribed to her and the manuscripts of Blanchot's first novels and reviews.

This unique, complete correspondence, as yet entirely unpublished and unknown to the bibliographers, covers the period from 1940 to 1991 (and some rare letters from an earlier time).

The first batch of letters – more than 230 composed between 1940 and 1958 (when Marie Blanchot died) – are addressed to his mother and sister who lived together in the family house at Quain.

Then, from 1958 to 1991, there are more than 700 letters addressed to Marguerite, including some without the Anna Blanchots' written part.

Eight letters addressed to his brother René and his sister-in-law Anna from the 1970s, with whom he would go living, were also retained by Marguerite.

And finally, there is a large set of letters written from 1962, addressed to his niece Annick and her son Philippe – grandson to Georges, Maurice's second brother.

Though Blanchot's intense affection for his mother and sister is evident from his inscriptions to them, we know almost nothing about their actual relationships. In the only biographical essay on Blanchot, Christophe Bident nonetheless tells us that: “Marguerite Blanchot worshipped her brother Maurice. Intensely proud of him…she attached great importance to his political thought…She read a lot…They would speak on the phone and correspond when apart; they shared the same natural authority, the importance attached to discretion.” Blanchot sent her a number of works from his library, demonstrating a previously unknown intellectual link.

The large number of letters addressed by Maurice to his sister reveal an intellectual complicity and a greater trust from the writer than he placed in almost anyone else close to him.#

The biographical part that dominates each letter reveals the intimate world – previously unknown – of the most secretive of writers. Essentially, he reveals himself as forthright with his sister and mother as intellectual and discreet with everyone else. Even his closest friends did not find out about the serious health problems that Blanchot faced throughout his life, which are laid bare here in detail.

Nonetheless, these intimate topics are only one aspect of this correspondence, which also aims to share the latest developments in the intellectual, social and political world – that Maurice Blanchot decodes for his little sister, who had sacrificed her independence and the artistic success she may have had as a noted organist for the sake of her mother.

Thus, from the Occupation to the Algerian war, from Vietnam War to the election of Mitterrand, Blanchot interprets for his mother and sister the intense and complex state of the world, sharing with them both his objective observations and his intellectual affinities, as well as justifying to them his standpoints and commitments.

An unembellished record, free of the posturing imposed by his intellectual status, Blanchot's correspondence with his family also has another unique feature: it is without doubt the only written record of the profound sensitivity of this writer who was known only for his outstanding intellect. This correspondence from the heart also reveals a Maurice fantastically benevolent towards his sister's and mother's religious convictions, and it is without any reticence that he punctuates his letters with explicit signs of the intense affection he bore for these two women – so different from the people in his intellectual set.

This precious archive covers the period from 1940 to the death of Marguerite in 1993. There is almost no trace of correspondence before this date, aside from a letter to his godmother in 1927, which leads one to suspect that the correspondence has been destroyed, perhaps at Blanchot's own request.

Among the letters to his mother and sister, we have identified some significant recurring themes.

Wartime letters in which Blanchot presents himself as both a reassuring son and a lucid thinker:

“Est-ce la mort qui approche et qui me rend insensible au froid plus modeste de l'existence?” (“Is death, as it approaches and makes me insensible to the cold, more modest than existence?”)

“Il n'y a pas de raison de désespérer.” (“There is no cause to despair.”) At worst, he says: “nous nous regrouperons sur nos terres. Nous trouverons un petit îlot où vivre modestement et sérieusement”; “la politique ne va pas fort. L'histoire de la Finlande m'inquiète beaucoup” (“we'll regroup on our own land. We'll find a little island where we can live humbly and seriously”; “the political situation is not good, and the situation of Finland seems to me very worrying.”)

“À la répression succèdent les représailles […] Cela ira de mal en pis.” (“Repression is followed by reprisals…It's going from bad to worse.”)

More personal news about his involvement and setbacks with various revues:

– Aux Écoutes, run by his friend Paul Lévy, whose flight to Unoccupied France he recounts,

– the Journal des Débats and the political upheavals that transformed it,

– his quitting of Jeune France upon Laval's return,

– his involvement in the survival of the NRF and the political challenges it faced during this difficult time.“Il est absolument certain qu'il n'y aura pas dans la revue un mot qui, de près ou de loin, touche à la politique, et que nous serons préservés de toute ‘influence extérieure'. À la première [ombre?] qui laisserait entendre que ces conditions ne sont pas respectées, je m'en vais.” (“It is absolutely certain that there will not be one word in the revue that touches on politics from a country mile, and that we will be spared all ‘external influence'. At the first [shadow?] of these conditions no longer being respected, I'll be off.”)

An astounding letter about the tragic episode that would become the subject of his final story, L'Instant de ma mort: “Vous ai-je dit qu'à force de déformations et de transmissions amplifiées, il y a maintenant dans les milieux littéraires une version définitive sur les événements du 29 juin, d'après laquelle j'ai été sauvé par les Russes! C'est vraiment drôle […] de fil en aiguille j'ai pu reconstituer la suite des événements” (“Did I tell you that via a process of distortion and exaggerations in its repetitions, there is now a definitive version circulating in literary circles of the events of 29 June, according to which I was saved by the Russians! It's really quite amusing…one step at a time, I was able to reconstitute the chain of events.”) He then recounts these at some length to his mother and sister, the same account – save for a few minor details – as presented in L'Instant de ma mort. “Et voilà […] notez comme la vérité est tournée à l'envers. … En tout cas c'est certainement ainsi ou peut-être sous une forme plus extravagante que nos biographes futurs raconteront ces tristes événements.” (“And there you have it, the truth turned upside down…in any case, it's certainly like this or in perhaps an even more extravagant form that our future biographers will recount these sad events.”)

This extraordinary letter throws (a very enigmatic) light on an event that we know only in its fictionalized form. At the heart of that fiction is…more fiction!

Letters from the Liberation period, in which Blanchot places special emphasis on his concern for the fate of Emmanuel Levinas:

“Son camp a été libéré, mais lui-même (à ce qu'un de ses camardes a affirmé à sa femme) ayant refusé de participer à des travaux, … avait été envoyé dans un camp d'officiers réfractaires. On craint qu'il lui soit arrivé ‘quelque chose' en route (et cela le 20 mars). […] Impénétrable destin.” His camp was liberated but he himself (so his comrades told his wife) having refused to work…was sent to a camp for recalcitrant officers. They fear that ‘something' may have happened to him en route (this on the 20 March)…An impenetrable fate.”)

He also mentions great emerging intellectual figures, both friends and not:

Sartre: “Il y a une trop grande distance entre nos deux esprits.” (“There is too great a distance between our two spirits.”)

Char: “L'un des plus grands poètes français d'aujourd'hui, et peut-être le plus grand avec Éluard.” (“One of the greatest contemporary French poets – perhaps the greatest, along with Eluard.”)

Ponge, who asked him for “une étude à paraître dans un ensemble sur la littérature de demain” (“a study to be published in a collection on the literature of tomorrow.”)

And Thomas Mann, whose death in 1955 affected him personally: “C'était comme un très ancien compagnon.” (“He was like a very old companion.”)

An observer of political events, he shows a benevolent but already suspicious interest towards General de Gaulle. “Comme homme, c'est vraiment une énigme. Il est certain que seul l'intérêt du bien public l'anime, mais en même temps, il reste si étranger à la réalité, si éloigné des êtres, si peu fait pour la politique qu'on se demande comment cette aventure pourrait réussir. […] Quand on va le voir, il ne parle pour ainsi dire pas, écoute mais d'un air de s'ennuyer prodigieusement. […] Il est toujours en très bons termes avec Malraux qui joue un très grand rôle dans tout cela. En tout cas, les parlementaires vivent dans la crainte de cette grande ombre.” (“As a man, he's a real enigma. Certainly, it is the public interest alone that drives him, but at the same time, he is nonetheless such a stranger to reality, so far removed from other human beings, and so little cut out for politics, that it's hard to see how this adventure could succeed…When you go and see him, he doesn't talk just for the sake of it, listening instead – but doing so with an air of profound boredom…He's still on very good terms with Malraux, who plays a big role in all this. In any case, parliamentarians live in fear of this great shadow.”)

But his view of the country's future remains strict: “La France n'est plus qu'un minuscule pays qui selon les circonstances, sera vassal de l'un ou de l'autre. Enfin, on ne peut pas être et avoir été.” (“France is nothing more now than a miniscule country which – depending on circumstances – will be a vassal of some other. In the end, you can't live for today while living in the past.”) Nonetheless, he followed the fate of Mendès-France as minister, whose fall he anticipated when he wrote: “Il sera probablement mort demain, tué par la rancune, la jalousie et la haine de ses amis, comme de ses ennemis.” (“He will probably be dead tomorrow, killed by the rancor, jealousy and hatred of both his friends and his enemies.”)

Post-war correspondence.

1949 marked a turning-point: “Pour mener à bien ce que j'ai entrepris, j'ai besoin de me retirer en moi-même, car la documentation livresque n'est profitable qu'à condition d'être passée par l'alambic du silence et de la solitude.” (“In order to complete successfully what I have begun, I have to retreat into myself, because written documentation in the form of books cannot be worthwhile except if it is first filtered through the still of silence and solitude.”) This is followed by long reflections on his relationship to writing and the world: “Je sais que la vie est pleine de douleurs et qu'elle est, dans un sens, impossible: l'accueillir et l'accepter … dans l'exigence d'une solitude ancienne, c'est le trait qui a déterminé mon existence peut-être en accord avec cette part sombre, obscure en tout cas, que nous a léguée le cher papa.” (“I know that life is full of painful things and it is, in one sense, impossible to welcome and accept that… seeking age-old solitude, this is perhaps the trait that determined my existence, perhaps together with that more somber part – more obscure in any case – that dear Father bequeathed us.”)

“Mon sort difficile est que je suis trop philosophe pour les littérateurs et trop littéraire pour les philosophes.” (“My difficult fate is that I am too philosophical for the literary types and too literary for the philosophers.”)

“Je suis radicalement hostile à toutes les formes de l'attention, de la mise en valeur et de la renommée littéraires – non seulement pour des raisons morales, mais parce qu'un écrivain qui se soucie de cela n'a aucun rapport profond avec la littérature qui est, comme l'art, une affirmation profondément anonyme.” (“I am radically opposed to all forms of attention-seeking, of self-promotion and literary fame – not only for moral reasons, but because a writer who is concerned with that has no real deep connection with literature, which is – like art – a profoundly anonymous affirmation.”)

Intellectual standpoint on Algeria.

“Quels lamentables et stupides égoïstes que les gens d'Algérie.” (17 mai 1958) (“What lamentable and stupid egotists the people of Algeria are”) (17 May 1958) “Et là-dedans l'intervention du Général qui achève la confusion.” (“and then there's the General's intervention to complete the confusion.”)

The day after the ultimatum sent by the conspirators of Algiers on 29: “Mon indignation est profonde, et je n'accepterai pas aisément que nous ayons pour maîtres à penser des légionnaires qui sont aussi, dans bien des cas, des tortionnaires” (“My indignation is profound and I will not easily accept that we have chosen to follow the lead of Legionnaires who are, in many cases, torturers.”)

“Le 14 juillet n'est pas destiné à continuer de paraître – c'est plutôt une bouteille à la mer, une bouteille d'encre bien sûr!” (“14 July is not destined to keep being published – it's more a message in a bottle – a bottle of ink, of course!”)

“Quant à notre sort personnel, il ne faut pas trop s'en soucier. Dans les moments où l'histoire bascule, c'est même ce qu'il y a d'exaltant: on n'a plus à penser à soi.” (“As for our personal fate, one mustn't worry too much. There is still something exultant in moments of historical upheaval: you no longer have to think of yourself.”)

“Cette histoire d'Algérie où s'épuisent tant de jeunes vies et où se corrompent tant d'esprits représente une blessure quasiment incurable. Bien difficile de savoir où nous allons.” (“This Algerian story where so many young lives are extinguished, and where so many spirits are corrupted, represents an almost incurable wound. Very difficult to know where we're headed.”)

“C'est bien étrange cette exigence de la responsabilité collective [Manifeste des 121] qui vous fait renoncer à vous-même, à vos habitudes de tranquillité et à la nécessité même du silence.” (“It's very strange, this demand for collective responsibility [the Manifeste des 121] which makes you renounce your very self, your habits of peace and even the necessity of silence.”)

Physical participation in May 1968.

“J'ai demandé qu'on envoie un télégramme à Castro: ‘Camarade Castro, ne creuse pas ta propre tombe'.” (“I've asked that they send a telegram to Castro: ‘Comrade Castro, don't dig your own grave.'”)

“Et je t'assure – pour y avoir été à maintes reprises – que ce n'est pas drôle de lutter avec des milliers et des milliers de policiers déchaînés…: il faut un énorme courage, un immense désintéressement. À partir de là s'établit une alliance qui ne peut se rompre.” (“And I assure you – having done so many a time – that it's not fun to fight with thousands and thousands of policemen let loose…you have to have enormous courage, an incredible disinterest. And from there, an alliance builds that cannot break.”)

“Depuis le début de mai, j'appartiens nuit et jour aux événements, bien au-delà de toute fatigue et, aujourd'hui où la répression policière s'abat sur mes camarades, français et étrangers (je ne fais pas entre eux de différence), j'essaie de les couvrir de ma faible, très faible autorité et, en tout cas, d'être auprès d'eux dans l'épreuve.” (“Since the beginning of May, I have been night and day at the service of events, beyond all tiredness and now, when police repression is practiced on my comrades, both French and foreign (I make no difference between the two), I try to spread over them my weak – oh so weak – protection, and in any case to be on their side in this time of trial.”)

“Cohn-Bendit (dont le père du reste est Français, ses parents ayant fui la persécution nazie en 1933), en tant que juif allemand, est deux fois juif, et c'est ce que les étudiants, dans leur générosité profonde, ont bien compris.” (“Cohn-Bendit (whose father, by the way, is French, his parents having fled Nazi persecution in 1933), as a German Jew is doubly Jewish, and it is this that the students, in their profound generosity, have understood.”)

“Voilà ce que je voulais te dire en toute affection afin que, quoi qu'il arrivera, tu te souviennes de moi sans trouble. L'avenir est très incertain. La répression pourra s'accélérer. N'importe, nous appartenons déjà à la nuit.” (“That's what I wanted to say to you with all affection so that, whatever happens, you will remember me without difficulties. The future is very uncertain. The repression could gather pace. It doesn't matter – we already belong to the night.”)

“Nous sommes faibles et l'État est tout-puissant, mais l'instinct de justice, l'exigence de liberté sont forts aussi. De toute manière, c'est une bonne façon de terminer sa vie.” (“We are weak and the State is all-powerful, but the instinct of justice, the need for liberty are strong as well. In any case, it's a good way to end one's life.”)

The 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, marked by a number of difficult challenges, were shot through with a growing pessimism. “L'avenir sera dur pour tous deux [ses neveux], car la civilisation est en crise, et personne ne peut être assez présomptueux pour prévoir ce qu'il arrivera. Amor fati, disaient les stoïciens et disait Nietzsche: aimons ce qui nous est destiné.” (“The future will be hard for both [of his nephews], because civilization is in crisis and no one can be presumptuous enough to foresee what will happen. Amor fati, as the Stoics said and also Nietzsche: let us love what is written for us.”)

“Je suis seulement dans la tristesse et l'anxiété du malheur de tous, de l'injustice qui est partout, m'en sentant responsable, car nous sommes responsables d'autrui, étant toujours plus autres que nous-mêmes.” (“I am but in the sadness and worry of everyone's misfortune, the injustice that surrounds us all, and I feel responsible, for we are all responsible for one another, being always more others than ourselves.”)

Still retaining his preoccupation with international affairs…: “Tout le monde est contre Israël, pauvre petit peuple voué au malheur. J'en suis bouleversé.” “Sa survie est dans la vaillance, sa passion, son habitude du malheur, compagnon de sa longue histoire.” (“Everyone is against Israel, poor little people destined for unhappiness. I'm stunned.” “Its survival lies in its watchfulness, its passion, and its being accustomed to misfortune, the companion of its long history.”)

“Comme toi je suis inquiet pour Israël. Je ne juge pas les Arabes; comme tous les peuples, ils ont leur lot de qualités et de défauts. Mais je vis dans le sentiment angoissé du danger qui menace Israël, de son exclusion, de sa solitude, il y a, là-bas, un grand désarroi, ils se sentent de nouveau comme dans un ghetto: tout le monde les rejette, le fait pour un peuple, né de la souffrance, de se sentir de trop, jamais accepté, jamais reconnu, est difficilement supportable.” (“Like you, I worry for Israel. I'm not judging the Arabs; like all peoples, they have their strengths and their faults. But I live in the anguish of the danger threatening Israel, of its exclusion, its solitude. There is, over there, great disarray, they feel they are once more closed in the ghetto: everyone turns their back on them – which, for a people born of suffering, which felt unwanted, never accepted, never recognized, is very hard to bear.”)

…as well as the domestic: “Mitterrand reste à mes yeux le meilleur Président de la République que nous puissions avoir: cultivé, parlant peu, méditant, les soviets le détestent.” (“Mitterrand remains in my eyes the best President of the Republic that we could have: civilized, taciturn, meditative; the Soviets hate him.”)

But it is without doubt the more personal letters in which he bears witness to his love and profound complicity with his correspondents which reveal the most interesting and most secret part of the personality of Maurice Blanchot. When, confronted with the tragedies of life, the son, brother or uncle expresses his love and his profound empathy, far from the pathetic commonplaces and received wisdom that is man's natural bulwark against misfortune, Maurice humbly offers his correspondent, to “ponder” the wounds of the soul, the form of words that is the highest expression of intelligence: poetry.

“Je pense à toi de tout cœur, et je suis près de toi quand vient la nuit et que s'obscurcit en toi la possibilité de vivre. C'est cela, mon vœu de fête. C'est aussi pourquoi, à ma place, et selon mes forces qui sont petites, je lutte et lutterai: pour ton droit à être librement heureuse, pour le droit de tes enfants, à une parole absolument libre.” (“I think of you with all my heart and I am near you when night comes and overshadows in you the possibility of living. There it is, my festive wish. That is also why, in my place, and in accordance with my resources – which are small – I fight and will continue to fight: for your right to be freely happy, for the right of your children to absolutely free speech.”)

“Attendons chère Annick, tu as raison, c'est souvent le silence qui parle le mieux. Les morts aussi nous apprennent le silence. Partageons avec eux ce privilège douloureux. Oncle Maurice.” (“But wait, Annick dear, you're right, it's often silence that speaks volumes. Deads, too, teach us silence. Let us share with them this sad privilege. Uncle Maurice.”)

Do you find collaborating more enjoyable than working on your own?

The reason that I do this is to discover, create, reveal and/or maintain connections with others. So collaboration is the pinnacle of musical experience. A couple of years ago, I made a record almost completely by myself. Then I played a heap of shows as a solo performer. In order for any of this activity to make sense to me, I needed to frame it as a deliberate and desperate act, as if I had come to the edge of a cliff at the end of the world with only one obvious exit.

Then I needed to look around and realize that there was another way, there were invisible collaborators who could airlift me out of that peril. These invisibles were/are the audience. I used to create music for an imagined audience, but I realized recently that I could accept that the audience was no longer imagined. They have become active collaborators. So that when I am on stage ‘by myself’ making music ‘alone’, in reality I am engaged in an active creative dialogue with the audience. They are completing the music then and there.

Will Oldham, interviewed

The drive, for me, in making music is not to express myself but to participate with others, including (and at times even especially) the audience/listener.

Will Oldham, interviewed.

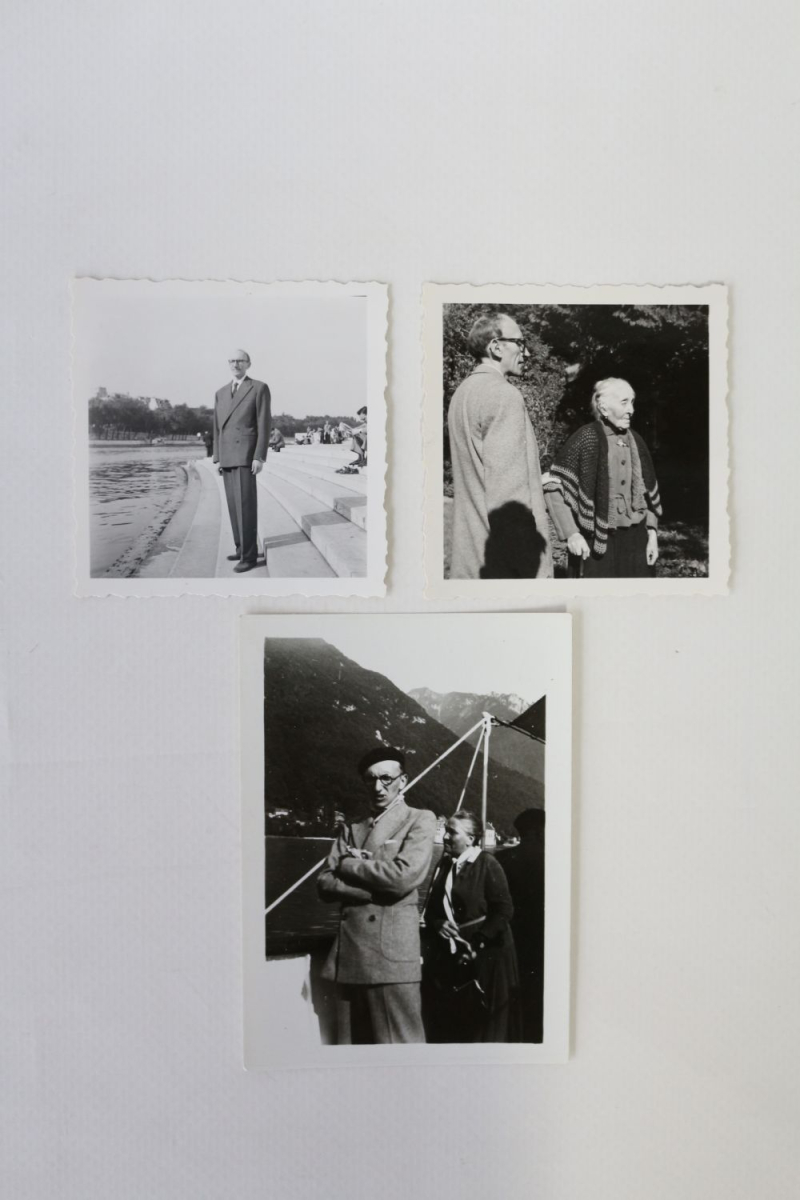

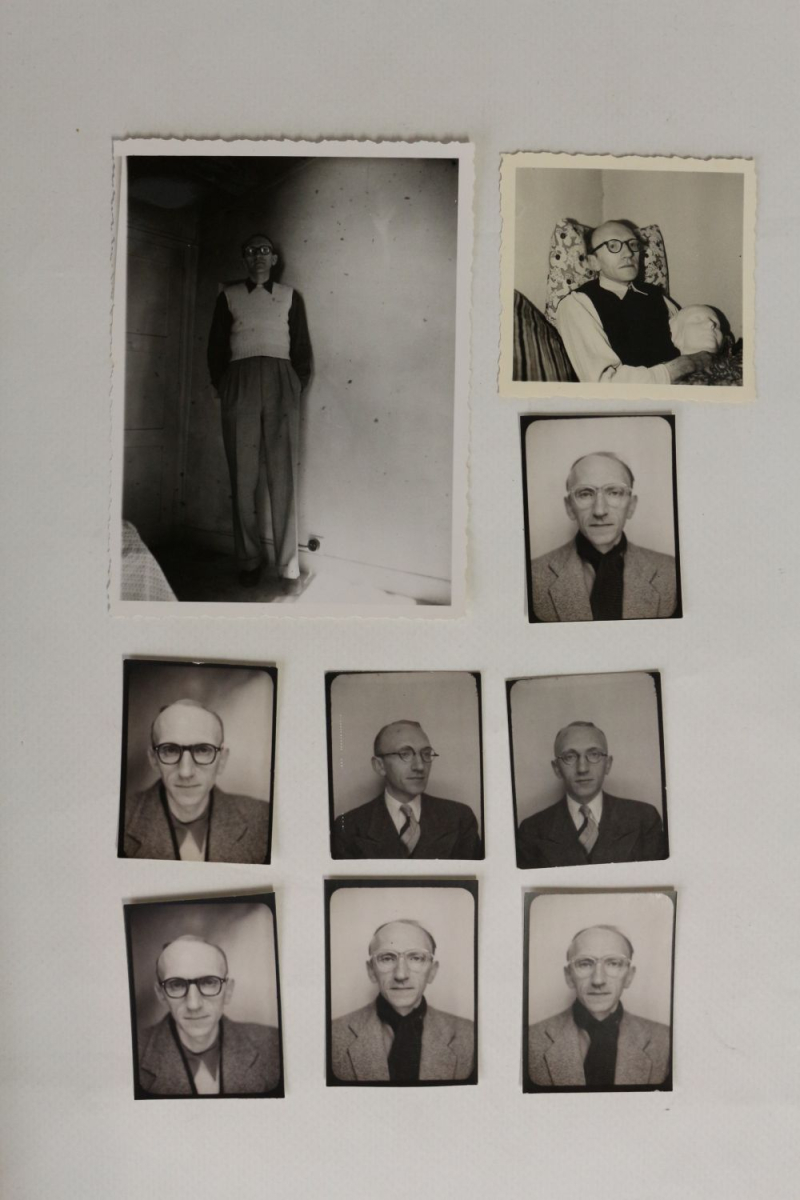

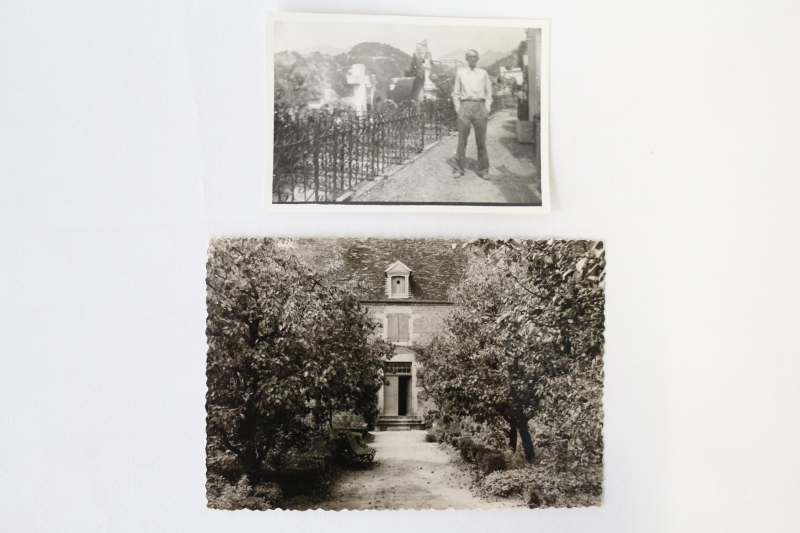

From an auction catalogue:

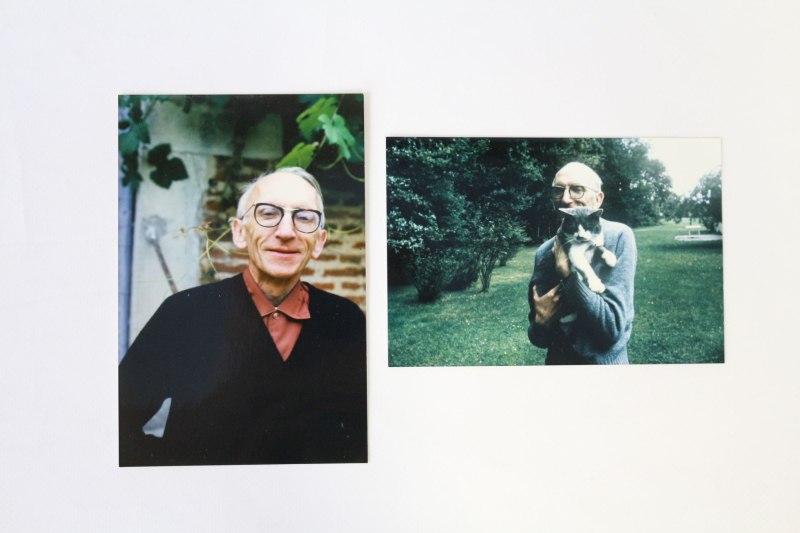

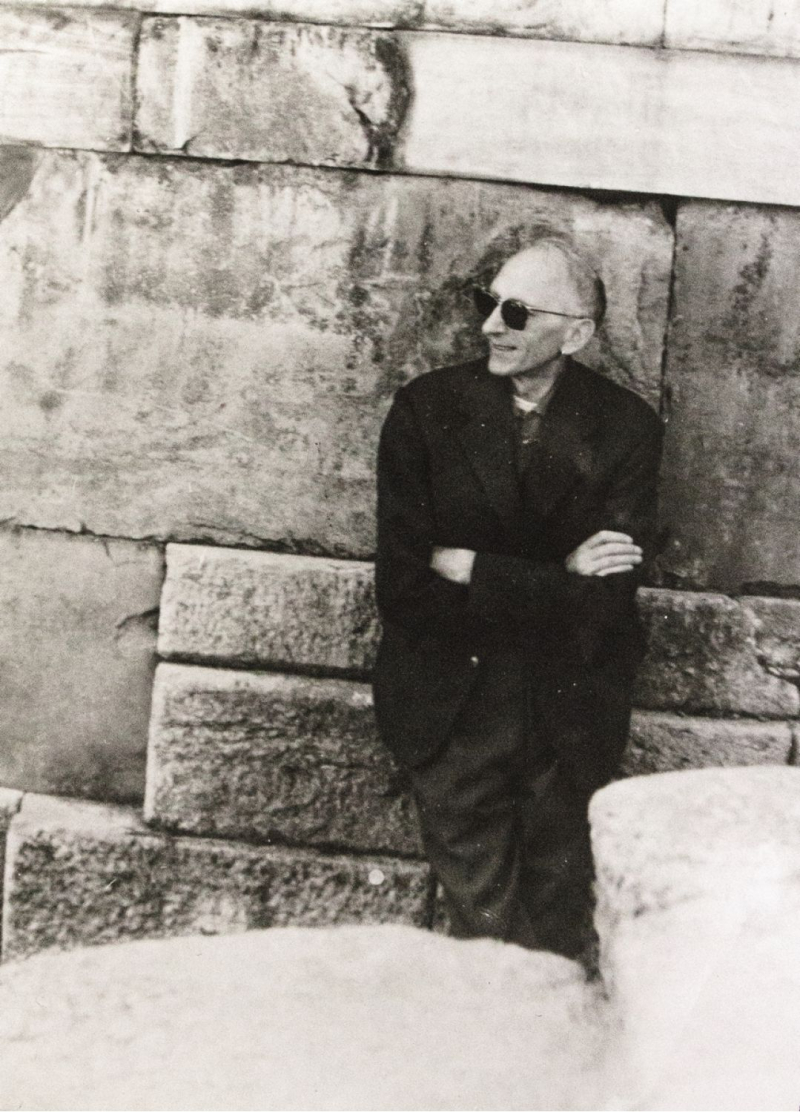

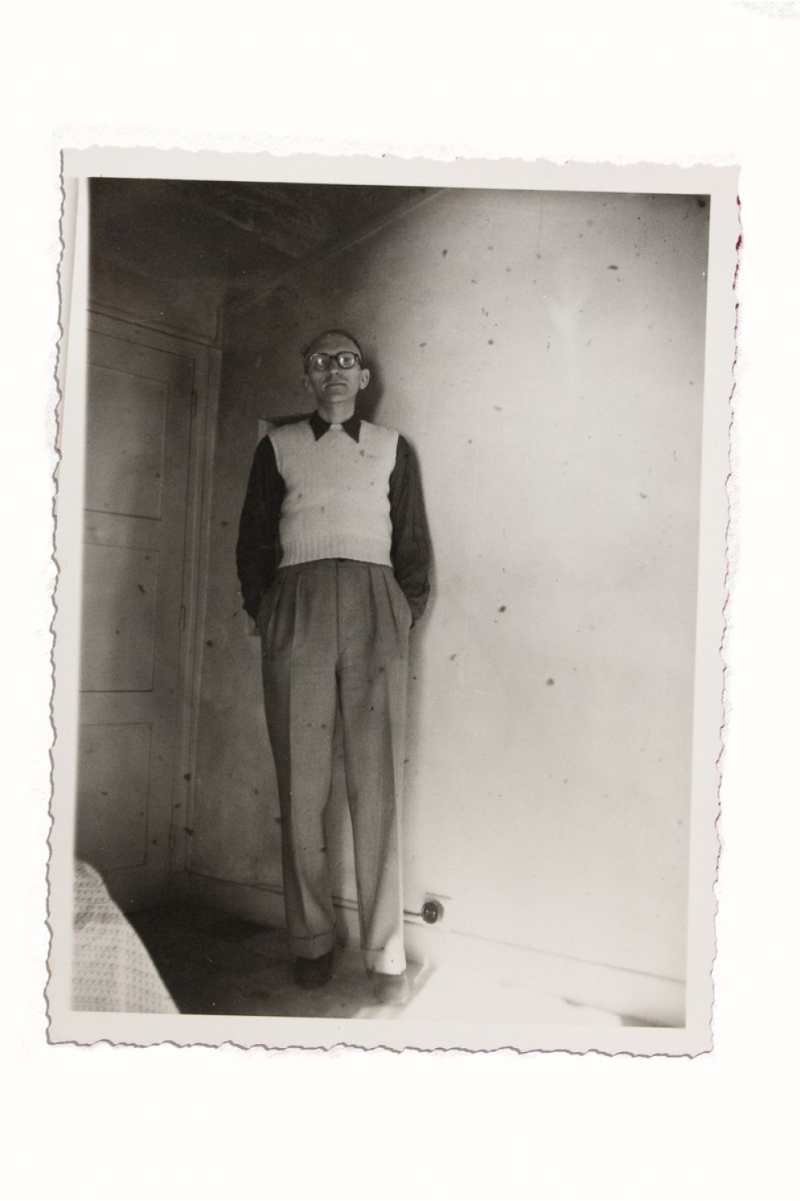

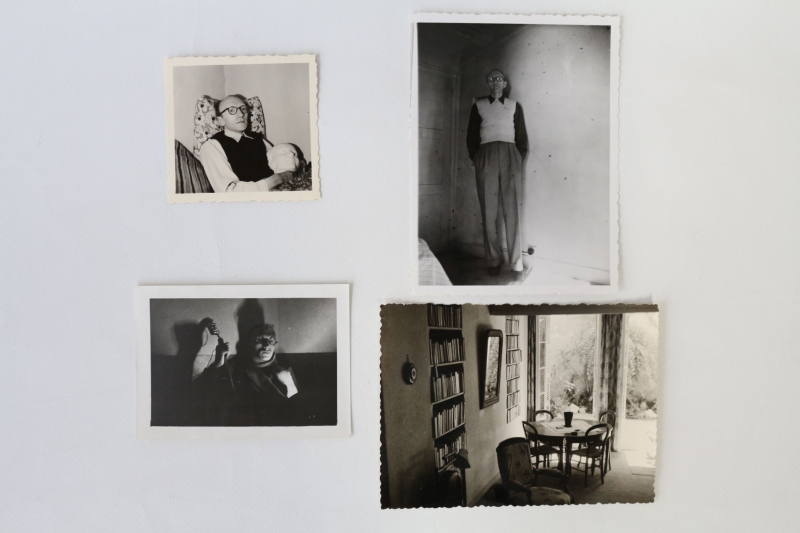

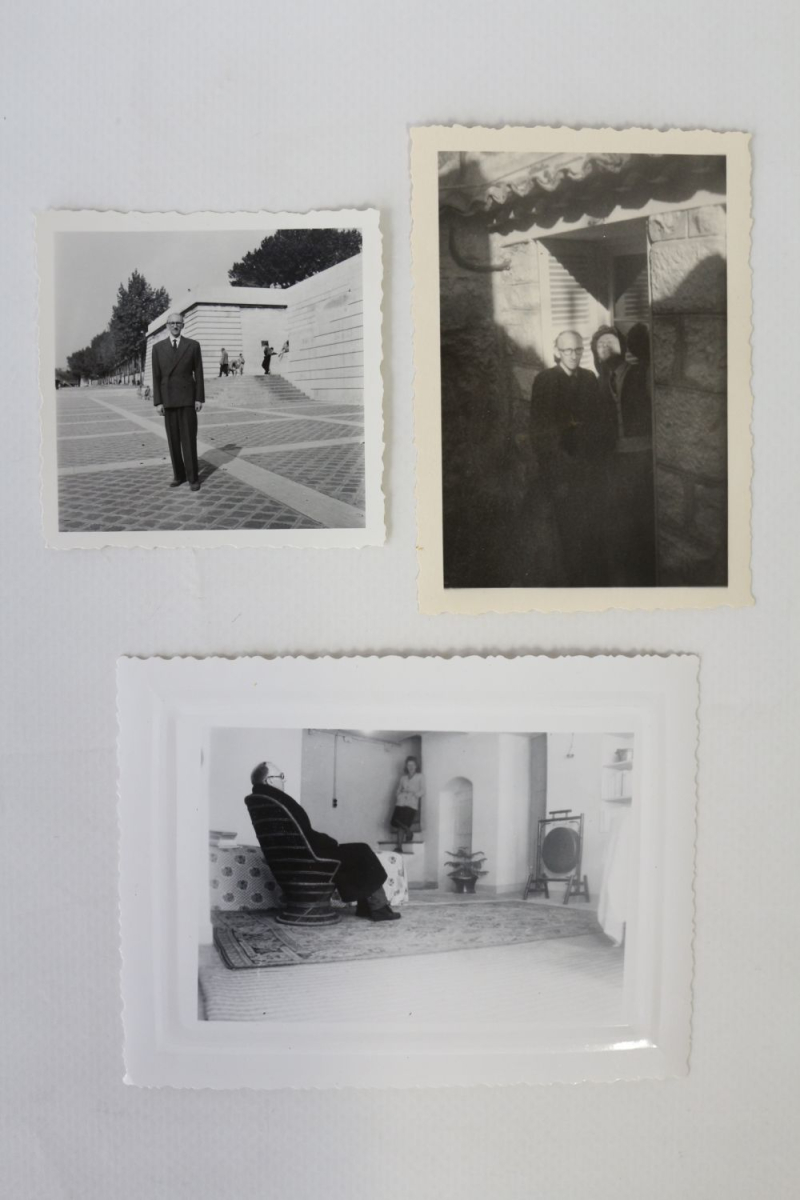

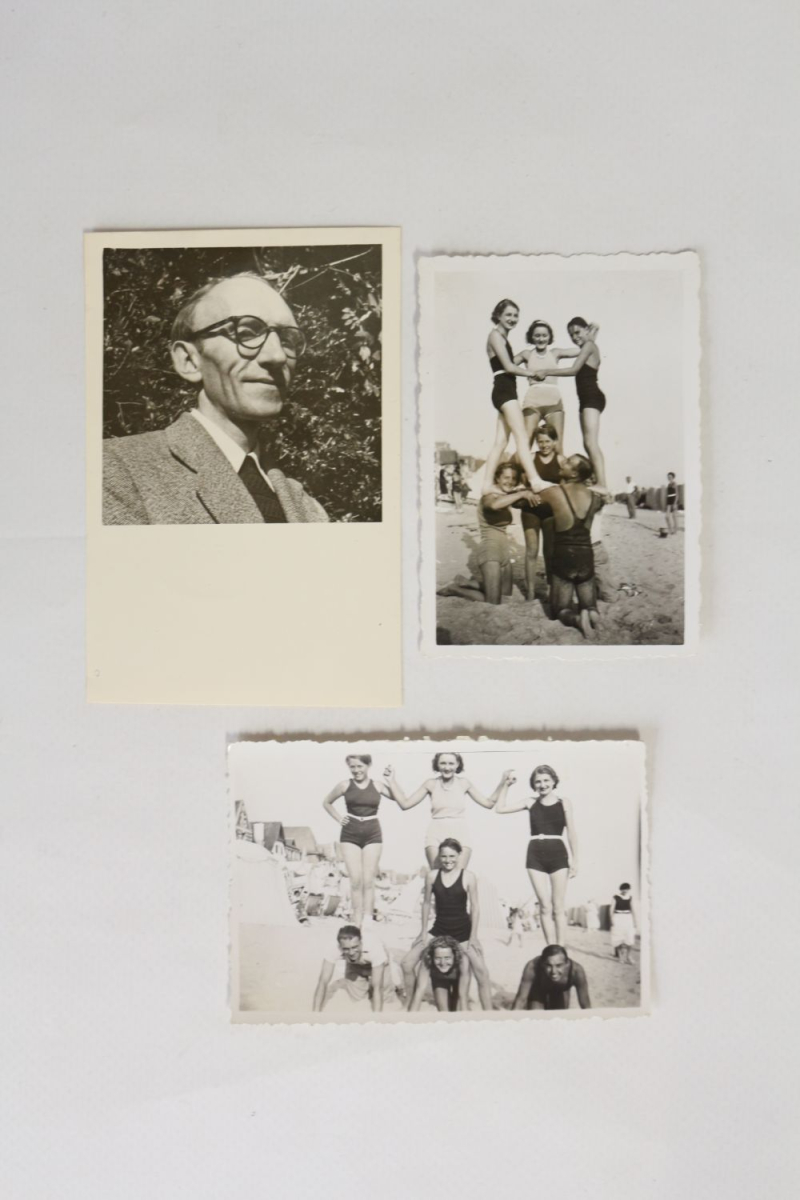

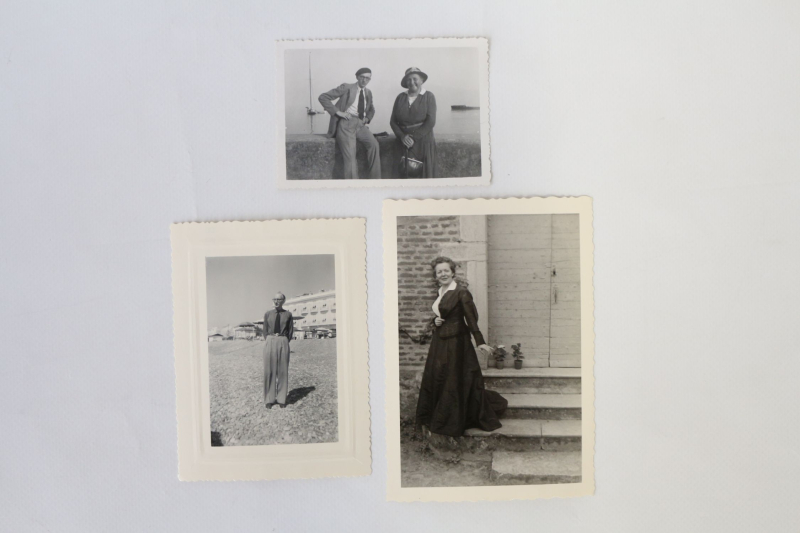

Extraordinary collection of Maurice Blanchot's original photographs taken in the family setting, the only printings

C. 1907-2003 | 272 photographs | various format

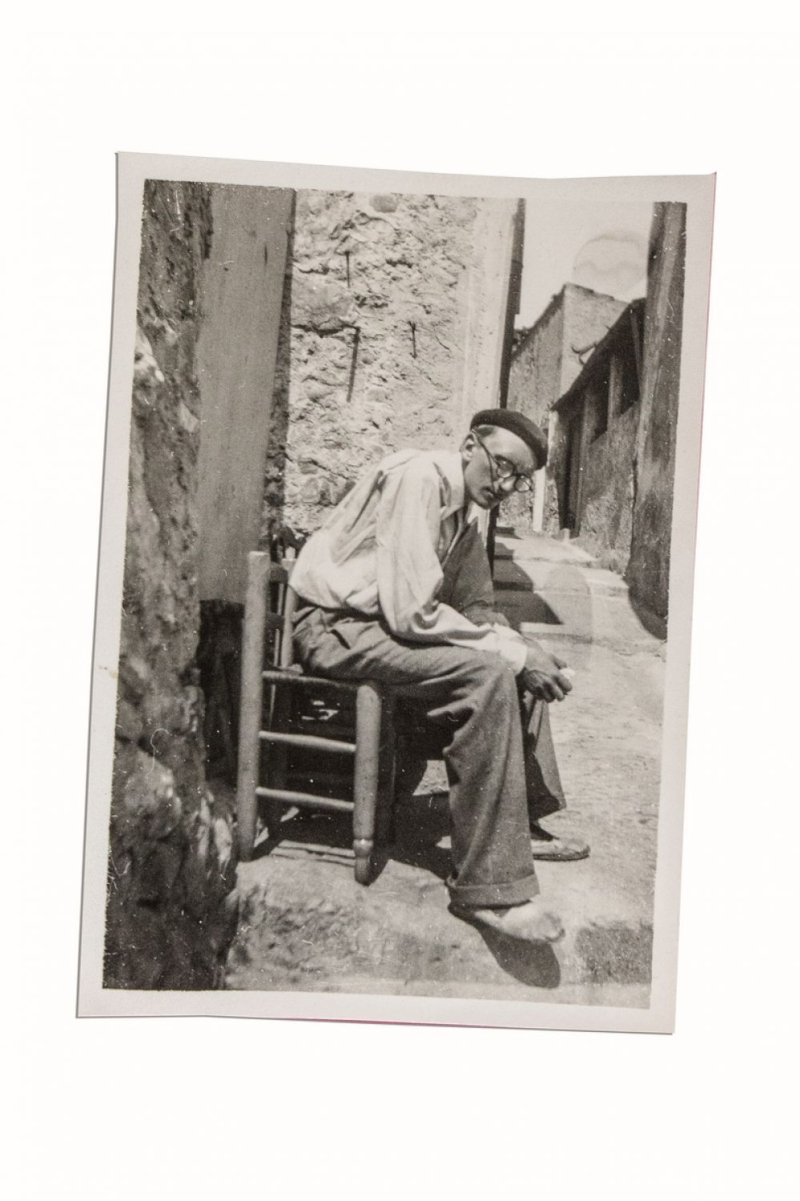

Blanchot challenged photographers and caricaturists of the literary press for a long-time. The illustrated sketches, over so many years, are minimalist and rare: in 1962 in L'Express, a hand holds up a book, at the bottom of the page; in 1979, in Libération, a blank square is in the middle of the page, with only Maurice Blanchot's name and a quote from the Entretien infini as a caption (‘an empty universe: nothing that was visible, nothing that was invisible')” (C. Bident, Maurice Blanchot).

In 1986, at the time of an exhibition of writers' portraits, he requested that his photo be replaced by a text showing his desire to “appear as little as possible, not to glorify [his] books, but to avoid the presence of an author who was entitled to an independent existence.”

A photo taken without him knowing by a paparazzi in a supermarket carpark, will be used as the writer's portrait for a long-time before his friend Emmanuel Levinas reveals a few rare portraits of their youth.

The fact that Maurice Blanchot did not oppose this release and the fact that this was his closest friend's deed, could be explained by what Bident calls “the spacing of worry,” the revealed portraits not being up-to-date echoing the postponed publications of L'Idylle, Le Dernier Mot, L'Arrêt de mort….

Only a few photographs gathered on the central pages of the Cahiers de l'Herne issue dedicated to Maurice Blanchot and published in 2014 supplement these unique shots of the twentieth century's most secret writer.

In his chapter, “The indisposition of the secret,” Christophe Bident devotes several pages to the almost total absence of images of this invisible partner, questioning the intellectual and psychological motivation of the writer who was aware of the inevitable future revelation:“Everything must become public. The secret must be told. The darkness must emerge. That which cannot be said must, however, be heard. Quidquid latet apparebit, all that is hidden, is that which must appear…” Maurice Blanchot, L'Espace littéraire)

In general, Maurice Blanchot refused to be photographed, even in his private life, as confirmed by the family of his sister-in-law Anna, who, in a letter to her nephew, told him that she had not taken any photographs of the writer, respecting his wishes.

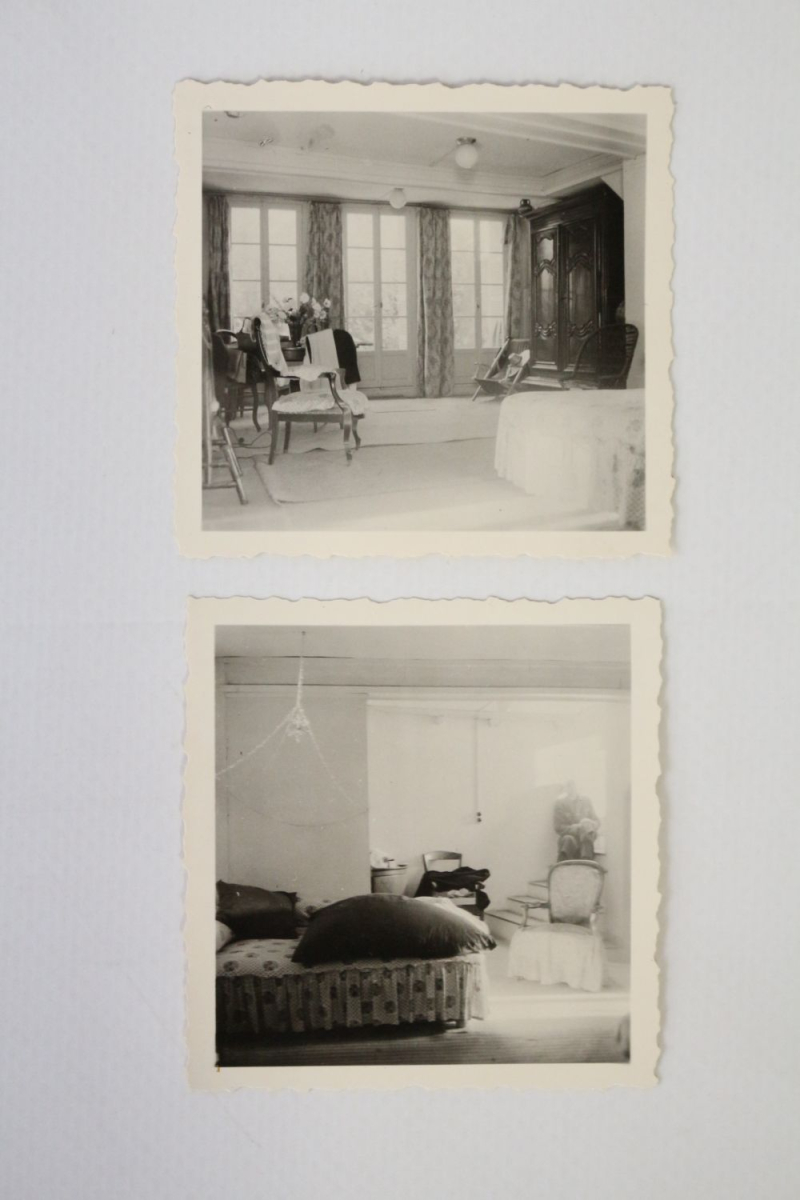

However, the photographs taken with his close family, show us a perfectly willing Blanchot, and one even playing very elegantly with the image of himself that he projects to the photographer, generally his brother. As such, we discover an elegant man posing proudly on a boat pontoon or on the banks of the Seine, or more mysteriously, playing with lighting effects in the corner of an empty room. Here we see a real photographic staging, and a symbolic reappropriation of image, particularly in this surprising seated portrait of the writer holding the “Inconnue de la Seine” death mask in his arms, the well-known plaster head of a young woman supposedly drowned and who adorned artists' studios after 1900. A true romantic legend, this sculpture with a mysterious post-mortem smile is at the heart of Aragon's novel, Aurélien, and haunts the work of artists at the beginning of the century, including Rainer Maria Rilke, Vladimir Nabokov, Claire Goll, Jules Supervielle, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Giacometti and Man Ray who, at Aragon's request, produced a worrying photographic portrait.

Maurice Blanchot described the unknown woman as “an adolescent girl with her eyes closed, but full of life with a smile so slender, so rich, […] that we could believe that she was drowned in a moment of extreme happiness.”

This photograph of an impervious Blanchot cradling the white mask of the “Mona Lisa of suicide” asserts itself as a true deconstruction of representation and an illustration, that is as perfect as it is enigmatic, of his literary work and of the “silence of its own.”

Numerous photographs bear witness to the same concern for the misuse of representation in favor of an aporetic symbolism, such as this full-length portrait of the writer dressed in black, blending into the receding perspective of buildings, but whose forehead only is encircled with a halo of harsh light that seems to spring from his skull and erase the roofs' contours. Or this other in which the light encircles half of an empty room with a halo and separates the photograph into two equal parts: a dark space at the point at which Maurice Blanchot holds his hands behind his back ad a lit space that is entirely empty, with the exception of one of the writer's feet which dares to cross over.

These photographs taken with his brother, show a perfect mastery of image and of his artistic codes.

Other photographs, with more classic compositions, bring a precious and unique testimony on Maurice Blanchot's life and on his family relationships, which constitute the writer's hidden side and his one true anchor to physical life. Maurice Blanchot, with whom his closest friends only usually had telephone contact, lived most of his life with his family. First of all in the family home in Quain, then hosted by his brother René and his sister-in-law Anna, where he will stay even after René and then Anna's death. Maurice will also have the most significant correspondence with his mother and his sister Marguerite (more than 1400 letters) throughout their lives, sharing with them all aspects of his intellectual, social and political life. Finally, his niece Annick, daughter-in-law of his brother Georges, and his young nephew Philippe were almost the only people authorised to enter René, Anna and Maurice's apartment, where the writer led a cut-off life. It is incidentally this niece and her son – a photographer – who will collect and preserve the precious photographic that bear witness to the writer.

Here we discover the slender figure of a man whose fragile constitution contributed to his dependence on his family, with whom the writer led a simple and happy life, posing naturally next to his mother, walking his nephew by the hand, sharing a family meal in the garden or talking in the living room. Blanchot's postures are those of a quiet man, not running from the lens and posing sometimes on the contrary with a certain, very assumed, dandyism. On several other photographs, Blanchot poses in the foreground in the same solemnly elegant pose, perfectly out of kilter with the landscape and the other people in the background. This repetition of the same pose in different settings gives Maurice Blanchot a ghostly, or at least unreal, presence.

However, these photographs also tell us, as much as they can, about Maurice Blanchot's private life, his travels, his relationships, his everyday world with his family and the different periods of his life. The photographs collected here start with family portraits on bistre albumin print, even showing the first months of Maurice Blanchot, and finish with color analogue photographs on Kodak paper, in which the writer is sat very seriously on his velvet sofa weighing up the camera in a low-angle shot, or, is mischievous in a green garden, hiding his face behind a cat that holds lovingly in his arms. Finally, as if to close this unique album of the only writer who managed to make himself invisible to the world during his life, a head and shoulders photograph, wearing a sweater that is deep black all over, shows us the writer's radiant face that seems to laugh at the great trick he played on his contemporaries.

With the exception of some identity shots and travel memories that he took at the end of his life, this unique and complete content is the only photographic source of Maurice Blanchot, of his living environment and his family, this private circle voluntarily hidden from the gaze and interest of the public and his friends, and yet it is at the root of the writer's contentious relationship with the outside world.

The photographs in this collection are much more than a mundane documentation from the side-lines of Maurice Blanchot's work; they bear witness to the real mastery of the image, its perspective and its power of reflexivity.

Like a final gift from the author of Thomas l'Obscur, these unique signs of his passage make the person who formerly disappeared behind his work suddenly reappear, bringing the miracle of his “Toma” (twin) to life: to be and not to be.

We sit in front of the TV until 10:00. We watch the press conference with Schranz. I top off Thomas’s glass of mulled wine, make remarks and comments several times, but Thomas maintains his icy silence for 2 ½ hours. I can’t believe it’s impossible to dispel his sullenness; I’m intent on at least getting a peep out of him. When the announcer on the television says that Karl Schranz is going to be flying to Innsbruck, I say: Schranz should have a fatal crash tomorrow; he reached his high point now; that would be the finest exit for him. Because in the future things can only go downhill for him. I was expecting at least a nod from Thomas, because death is his pet topic, and Thomas smiles or smirks like a shot at everything that has to do with death or has some connection with death. He remained icy. At 10:00 he stood up, said “Good night” to my family. I accompanied him to the front door. Ordinarily I walk with him to his parking space as we chat; this time I stayed put at the front door and said “Good night” only belatedly. You see, he left without making any kind of salutation.

Karl Ignaz Hennetmair, from A Year With Thomas Bernhard, translated by Douglas Robertson