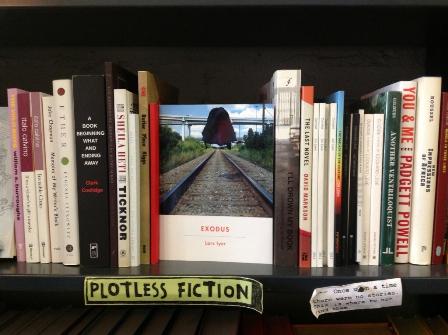

E. J. Iannelli's review of Exodus from Rain Taxi, Summer 2013 print edition (vol.18, no.2, #70):

When Martin Amis's Lionel Asbo was published last year, its cover bore the pretentious subtitle State of England. According to the author, this was an ironic nod to a 'very boring, monotonous' subset of British fiction concerned with precisely that. Of course, Amis's sneering aspersions on the 'state-of-England' novels weren't tempered by the fact that his own father's work might be counted among them. The subtitle also handed several critics a club with which to give Lionel Abso the sound beating its chavvish antagonist so desperately needed.

Unlike Amis, Lars Iyer isn't so bold as to position his bleak comic trilogy as a definitive sociopolitical take on anything. The trilogy itself has no overarching title; the episodic books that comprise it were awarded just one thematically significant award each: Spurious, which debuted in 2011, followed by Dogma (2012) and then Exodus (2013). Instead Iyer leaves the pontificating to his characters, two hapless philosophy lecturers named W. and – in a fittingly meta sort of way – Lars. The pair is very much concerned – to a monomaniacal degree of fixation – with the state of England, symbolized by places like Oxford University, "this facade of old England, this facade of study, this facade of research," which has allowed itself to be steamrolled by the "privatisation of thought," part of a capitalist phenomenon that is driveing the closure of university philosophy departments across the country.

Aside from Lars's corpulence and general wretchedness, this cultural collapse is the duo's sole topic of conversation – or rather, the sole topic of W.'s sententious diatribes, since Lars seems to exist only to serve as his companion's whipping boy and stenographer. As they pine for the halycon days when philosophers were "remade in thought's crucible" and contemplate the future that is destined to spring from this grim present, W. and Lars are moved to an all-consuming form of despair of Kierkegaardian proportions. The profundity of their despair gives them a perverse satisfaction – or at least something else to kvetch about.

Spurious, as the title suggests, was loosely about claims to authenticity. W. dreamed of thinking 'a single thought that might justify his existence' while he and Lars continued a longstanding quest to find someone, anyone they might call their philosophical messiah. In Dogma, the two ventured abroad to America, and, thwarted, set about imagining the foundation of a new philosophical system. Here, in Exodus, this Laurel-and-Hardy duo are wandering Jews – or more specifically, a dubious practitioner of Hinduism and a blowhard with vague claims to Judaism – who, now cast out of the comfort of their ivory towers, are engaged in a peripatetic search for a new homeland. But instead of a Moses to lead them toward the promised land of Canaan, they have W., who pulls them toward a bygone Essex.

The utter hopelessness of Exodus's England – there are extended ruminations on melancholy, despair, and "life-disgust" - is offset by the Beckettian comedy of its bumbling interlocutors, whose peculiar dynamic is reminiscent of Withnail & I. W. is an amalgamation of several comic archetypes: the pompous academic, the obnoxious self-loathing drunkard, the beta male in the company of omegas. Lars is an inherently absurd figure, the sort who only seems to exist in novels and movies. Yet he takes life off the page. The lingering image is one of him transcribing W.'s bloated rhetoric in a pink notebook with a purple pen ("like a Japanese schoolgirl"), suffering W.'s relentless insults without protest ("Do you have a sense of your idiocy?" W. prods during one boozy, gin-soaked interrogation; "Do you grasp just how desperately you have fallen short?"), a copy of the celebrity tabloid Hello! and ample snacks always by his side like a child's security blanket.

Compared to the previous novels, however, Lars is a diminished presence. Not in terms of girth) at one point (at one point, W. makes a show of Googling "morbid obesity," "liposuction" and "gastric bands" to drive a particularly humiliating point home) but rather his very selfhood. He does manage to rise to the occasion for a couple of rousing speeches, much to W.'s vocal surprise, but on the whole he exists under his companion's thumb. Here, in the final book of this trilogy, this self-styled scholar and philosopher has the entirety of his thoughts dictated to him by a man who professes to have no worthwhile thoughts. Here he is doubly in thrall to a washed-up mentor who openly regards him as "a living excuse for his failure, his inability to think."

And therein lies the sly subversiveness of Iyer's tragiccomic trilogy – and it is indeed tragic, given that W. and Lars's lamentations are at least partially rooted in real-world events. When, all the way back in Spurious, W. moaned that "we're fucked, everything's fucked" and insisted to Lars that they "should only speak of each other to others in world-historical terms," he was echoing a more grave and pervasive sentiment that we – that is, not just England in its current state, or America, but all of humanity – are hastening toward end times on all possible fronts: political, social, environmental and, yes, even educational. Amid the onslaught of W.'s facetious blotivation, his droll lists of all the ways in which Lars gives expression to his idiocy, his reflexive parody of the academic philosopher, Exodus and its two predecessors place serious points on the table: the danger of political defeatism, the idea that thought "is indistinguishable from dread," or the question of finding the path to salvation "in truly experiencing our despair."

"Philosophy gives substance to our suffering," W. expounds at one point. "That's what does combat with the senselessness of the world." And there's a genuine kernel of truth in that, despite its supercilious fictional source. With Exodus, as he did with Spurious and Dogma before it, Iyer has shown that a picaresque novel can be as good a vehicle for philosophy as any.