Category: Uncategorized

I translated Blanchot’s texts because I felt a kinship there. I liked his lack of pretentiousness, his way of going deeply into a small, mysterious moment of interaction between people—or between abstractions that he treated as characters. I liked the fact that he didn’t need a dramatic story line.

Lydia Davis, interviewed

Jonathan Ross versus Aki Kaurismäki, from 1991.

'What is surprising is not that things are; it's that they are such and not other', Valéry writes in the 'Note et digression' he appended to his Leonardo essay in 1919. This is profoundly opposed to the pragmatic and positivist English tradition, which takes the world and ourselves for granted and sees the task of art as the simple (or not so simple) exploration of the vagaries of life and the problems of mortality. it is this, we could say, that makes it difficult for the English to respond to the manifestations of European modernism, which is too often accused of 'abstraction' and 'deliberate obfuscation', whether it be the poetry of Rilke and Paul Celan, the philosophy of Heidegger and Derrida, or the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet and Thomas Bernhard. For the English reader and critic, not to be interested in nature for its own sake, not to be interested in the moral dimension of murder and adultery, is not merely a literary but a human failing, a sign of a fatal abstraction, an unwillingness to engage with life as it is. For Valéry or Robbe-Grillet, to be interested in a tree or a bird – or a murder or a jealous husband – for its own sake, is to be concerned merely with the anecdotal and ephemeral. What interests them is what bird-leaving-tree tells us about our condition, it is the nature of murder and of jealousy.

Gabriel Josipovici, The Teller and the Tale

Our epoch does not love itself. And a world that does not love itself is a world that does not believe in the world: we can believe only in what we love. This is what makes the atmosphere of this world so heavy, stifling and anguished. The world of the hypermarket, which is the effective reality of the hype-industrial epoch, is, as an assemblage of cash registers and barcode readers, a world in which loving must become synonymous with buying, which is in fact a world without love.

from Bernard Stiegler, Uncontrollable Societies of Disaffected Individuals

They were the worst of times because they were the best of times; times in which dissent was forbidden, not by the dispersal of dissenters but by their assembly; times in which protest was refused, not by the containment of expression but by its freedom; times in which the people were kept in ignorance, not by narrow educational channels but by immeasurably wide ones; times in which we were made to forget the evils all around by hysterical remembrance of evils dead and gone; in which we were half-dead, not from neglect but from care, and half-mad, not from silence but from talk, and starved out of our wits from much too much to eat; in which want had the form of plenty, and dearth the form of glut, and no one could think their way out, not because there was too little time to think but because there was far too much.

There is in these times such an explosion of thinking, such licence to think and rethink, to think from all angles and all perspectives, to think of ourselves and of others and of others like ourselves and of others unlike others, to think and think and think again, that we cannot any longer think straight.

the opening of Sinéad Murphy's forthcoming Zombie University

I read [Deleuze's] Logic of Sense a long time ago, 30 or 34 years ago, in fact I was in prison when I read Logic of Sense, and I think that it is reading Logic of Sense that permitted me to live in prison. Logic of Sense allowed me to live in prison and to adopt an ethics of prison. What I call an ethics of prison is one which permits me to cultivate a virtue, for me an ethics cultivates a virtue.

Bernhard Stiegler, speaking in a seminar

If we have to live through what Nietzsche called ‘the fulfilment of nihilism’ that is, so to speak, the concretization of the ‘death of God’, then we must pose the question of God – which is obviously not the same as resurrecting Him. Today, we live the ordeal of nihilism; today, nihilism presents itself as such, that is, in the form of the experience that I am nothing. For a long time it did not present itself as this nothing. It presented itself as ‘anything goes’, ‘I can do it all’, ‘I can transgress’. When nihilism presents itself as such, can I recognize it? What is it that I am living? What is my experience? It is the experience of what Kierkegaard already described as despair. When despair becomes the most common experience, the most widespread, it is no longer possible to ignore the specific questions raised by the death of God, the questions, dare I say, worthy of the death of God. We are in the course of living through what we could call, in religious language, the ‘apocalypse’ of nihilism. It is here that we must become worthy of the ordeal of nihilism. By suggesting that he himself arrives to soon with this statement, Nietzsche in some way says to us: ‘I await the moment when you will truly encounter nihilism. Now I am speaking to you and you believe you understand me. But in fact you do not understand me at all. You believe you understand, but you do not understand because if you understood, you would be living through your apocalypse.’

Bernard Stiegler, interviewed

With its careful attention to Justine’s condition, and especially with Dunst’s amazingly sensitive and nuanced performance, Melancholia refutes clinical objectivity, and instead depathologizes depression. For depression is all too often stigmatized as a moral or intellectual failure, a kind of unseemly self-indulgence — this seems to be John’s attitude towards Justine. Or else, at best, depression is understood reactively as a deficiency in relation to some supposedly normative state of mental health — this seems to be Claire’s attitude. But Melancholia suggests that both these positions are inadequate. By focusing attention so intensively upon Justine’s own emotions, it treats depression as a proper state of being, with its own integrity and ontological consistency. This is not the least of the film’s accomplishments.

I would go so far as to say that, in this regard, Melancholia is profoundly antiNietzschean[…] For Nietzsche has no empathy at all with the state of depression. Rather, he stigmatizes it in emphatically normative terms. Nietzsche insists upon “the futility, fallacy, absurdity, deceitfulness” of any “rebellion” against life. “A condemnation of life on the part of the living,” he writes, “is, in the end, only the symptom of a certain type of life.” Even the judgment that condemns life is itself “only a value judgment made by life”: which is to say, by a weak and decadent form of life. Nietzsche seeks to unmask all perspectives — even the most self-abnegating ones — as still being expressions of an underlying will to life. This universal cynicism is the inevitable counterpart of Nietzsche’s frequent, and strident, insistence upon the necessity of “cheerfulness.”

Contrary to all this, Justine’s will to life has been suspended. Her depression is a kind of positive insensibility or ataraxia, or even what Dominic Fox calls “militant dysphoria”. This is a state of being that no longer sees the world as its own, or itself as part of the world. As Fox puts it, “the distinction between living and dead matter collapses. The world is dead, and life appears within it as an irrational persistence, an insupportable excrescence”. Through its refusal to affirm or celebrate life, dysphoria subtracts itself from the will to power, and therefore from Nietzsche’s otherwise universal suspicion about motives. Depression is the one state that cannot be unmasked as just another expression of the will to power. The underlying assumption of Nietzsche’s entire critique of both morality and nihilism is that the human being, and indeed every organism, “prefers to will nothingness rather than not will”. But depression, at least in von Trier’s presentation of it, must be understood as a positive not-willing, rather than as a will to nothingness, or a destructive (and self-destructive) torsion of the will.

From Steven Shaviro's great esssay on Melancholia

My mother gave me away.

In Holland – in Rotterdam – for a year, I was kept on a fishing trawler with a woman. My mother came to visit me there every three or four weeks. I don't think that she cared much for me at the time. However, this then changed.

I was a year old, we went to Vienna … and then the mistrust, lingering still when I was brought to my grandfather, who by contrast, really loved me, changed.

Then taking walks with him – everything is in my books later, and all these figures, male figures, this is always my grandfather on my mother's side … But always – except for my grandfather alone … the consciousness that you cannot step outside of yourself.

All else is delusion, doubt. This never changes …

In school years completely alone.

You sit next to a schoolmate and you are alone.

You talk to people, you are alone.

You have viewpoints, differing, your own – you are always alone.

And if you write a book, or like me, books, you are yet more alone …

To make oneself understood is impossible; it cannot be done.

From loneliness and solitude comes an even more intense isolation, disconnection.

Finally, you change your scenery at shorter and shorter intervals. You think, bigger and even bigger cities – the small town is no longer enough for you, not Vienna, not even London. You've got to go to some other part of the world, you try going here, there … foreign languages – maybe Brussels? Maybe Rome?

And there you go, all over the place, and you are always alone with yourself and your increasingly dreadful work.

You go back to the country, you retreat to a farmhouse, like me, you close the doors – often days long – stay inside, and the only joy – and at the same time ever greater pleasure – is the work. The sentences, words, you construct.

Like a toy, essentially – you stack them one atop the other; it is a musical process.

If a certain level should be reached, some four, five stories – you keep building it up – you see through the entire thing … and like a child knock it all down. but when you think you're rid of it … another ulcerous growth like it is already forming, an ulcer that you recognise as new work, a new novel, is bulging somewhere on your body, growing larger and larger.

In essence, isn't such a book nothing but a malignant ulcer, a cancerous tumour?

You surgically remove it knowing of course perfectly well that the metastases have already infected the entire body and that a cure is completely out of the question.

And of course it only gets worse and worse, and now there is no rescue, no turning back.

Thomas Bernhard, extemporising in 3 Days

Now up at the NCLA archives, Gabriel Josipovici and I discussing his work.

“Friend” and “free” in English, and “Freund” and “frei” in German come from the same Indo-European root, which conveys the idea of a shared power that grows. Being free and having ties was one and the same thing. I am free because I have ties, because I am linked to a reality greater than me.

To the question, “Your idea of happiness?” Marx replied, “To fight.” To the question, “Why do you fight?” we reply that our idea of happiness requires it.

Writing is a vanity, unless it's for the friend. Including the friend one doesn’t know yet.

Life and the city have been broken down into functions, corresponding to “social needs.” The office district, the factory district, the residential district, the spaces for relaxation, the entertainment district, the place where one eats, the place where one works, the place where one cruises, and the car or bus for tying all that together are the result of a prolonged reconfiguration of life that devastated every form of life. It was carried out methodically, for more than a century, by a whole caste of organizers, a whole grey armada of managers. Life and humanity were dissected into a set of needs; then a synthesis of these elements was organized. It doesn’t really matter whether this synthesis was given the name of “socialist planning” or “market planning.” It doesn’t really matter that it resulted in the failure of new towns or the success of trendy districts. The outcome is the same: a desert and existential anemia. Nothing is left of a form of life once it has been partitioned into organs. Conversely, this explains the palpable joy that overflowed the occupied squares of the Puerta del Sol, Tahrir, Gezi or the attraction exerted, despite the infernal muds of the Nantes countryside, by the land occupation at Notre-Dame-des-Landes. It is the joy that attaches to every commune. Suddenly, life ceases being sliced up into connected segments. Sleeping, fighting, eating, taking care of oneself, partying, conspiring, discussing all belong to the same vital movement. Not everything is organized, everything organizes itself. The difference is meaningful. One requires management, the other attention—dispositions that are incompatible in every respect.

From The Invisible Committee's magnificent To Our Friends

Psychologically, Justine’s reactions are not willful, so much as they are compelled by extreme distress. But beyond this, Justine’s depression is ontological in scope. It cannot be characterized as just a contingent response to one particular set of circumstances. For it involves the rejection of any “particular circumstances” whatsoever. Justine’s depression marks a rupture with the social order as such: an order that cannot function without the tacit complicities and denials that are understood, and entered into, by everyone. In refusing this, Justine enters into a condition that is absolute and unqualified. Her depression is ungrounded, self-producing and self-validating. It needs no external motivation or justification. It is just what it is: an unconditioned and nonreflexive state of pure feeling.

From Steven Shaviro's great esssay on Melancholia

The nations will fall. The old kingdoms. The old empires. The governments will fall. There’ll be no more progress, expansion or growth. The gypsies will take what they always took – the rubbish, the ruins, the alms. Nothing else mattered to them. Centuries of thrift and tradition. The gypsies will win. They’ll outlast us. They’ll know how to live. They’ve been practising all these years for the apocalypse.

Andrej Stasiuk, Road to Barbadag

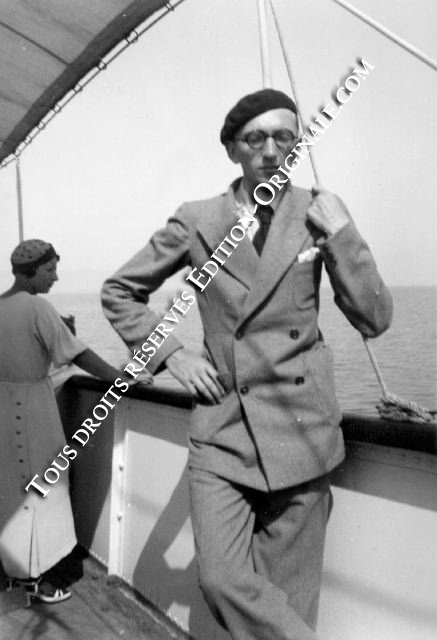

Three photos of Blanchot – the first two, new to the net; the third, new in colour.

But how, one might ask, did this most unusual emphasis upon distance, impersonality, and loss come to assert itself within Blanchot’s account of intimate relationality? Ironically, When the Time Comes, which makes impersonal relations one of its principle themes, is ultimately a récit inspired by personal events. It is difficult to read what Blanchot tells us about distance, intimacy, and loss, particularly in the text’s final pages, without thinking constantly of the name that reverberates silently throughout its margins: Denise Rollin.

Much of what we know about Blanchot’s relationship with Rollin comes from the Bident and Surya biographies. These studies are admirable for their scope and precision, but both are somewhat disappointing to the extent that they fail to offer us any serious discussion of Rollin’s influence on Blanchot’s work and thought. A likely reason for this is that, until now, the matter itself has remained largely speculative. We know that Blanchot was introduced to Rollin in the autumn of 1941, not long after the publication of Thomas the Obscure. Over the next year and half, the two of them would meet nearly twice a month, along with Bataille (who was her lover at the time) and others, at 3 rue de Lille.

By all accounts, the Blanchot who participated in these discussions presented himself as the very embodiment of modesty and discretion. And Rollin, who was fond of professing that there could be “no grandeur unless it [was] accompanied by a great humility”, was naturally drawn to him. “M.B. is the being with the utmost humility that I know,” she would later confide; “he resembles most incredibly Dostoevsky’s ‘Idiot’ . . . yet he is altogether unconscious of all this”. This unconsciousness, this absence from himself, as Bident claims, “is precisely what attracted her. . . . This movement of self-effacement, of being nobody, is what seemed to fulfill her”.

By the time they met, Rollin was thirty-four (as was Blanchot) and recently divorced, with a young son. She was already well known in avant-garde circles and had cultivated, throughout the 1930s, close friendships with a number of surrealist artists and writers, including Breton himself. During autumn 1943, Rollin grew particularly close to Blanchot, and by the middle of 1945, as Bident tells us, the two had become lovers. What followed, over the next few years, was the most significant romance of Blanchot’s adult life, a relation amoureuse that nevertheless came to be disrupted, repeatedly, by the imposition of distances, disappointments, and deferrals. It was a relationship, moreover, based from the very start on a profound sacrifice: toward the end of the 1950s, Rollin would write to a friend, “This now makes fourteen years that I refuse Maurice Blanchot — who nevertheless is the being destined for me”.

Counting backwards (some fourteen years) from the date of her letter, one arrives at November 1945; Blanchot’s important early essay on Nietzsche was about to be published, and Blanchot was leaving Paris for Beausoleil. He would return to the capital the following spring, only to leave again less than four months later. Such peregrination was, for Blanchot, less the exception than the rule. By the winter of 1946, he had moved again — this time to the little house in Èze where, in the months that followed, he would begin work on When the Time Comes — a text “written for Denise”. It was over the course of this year and a half that the refusal to which she refers in her letter began to take shape.

Although the exact circumstances surrounding it remain largely unknown to us, in his biography Bident leads us to believe that the correspondence conducted

between Blanchot and Rollin during this period was considerable, with her letters, in particular, characterized by a high style and intensity. As for Blanchot’s letters — we can only speculate. Yet what we do know is that his critical writings from around this time are some of his most important early pieces, many of which bear witness to a burgeoning obsession with themes whose prominence would only increase in the years that followed: the affirmation of extreme distance, the contestation of teleology, the movement of eternal return.

From Joseph Kuma's excellent Eroticization of Distance: Nietzsche, Blanchot and the Legacy of Courtly Love

Laish, 'Vague', inspired by Spurious, at last on a studio recording. From the new album Pendulum Swing.

MINETTI:

We actors are constantly searching

trageduy

or comedy

if you really think about tragedy

with a clear head

you can see at heart it's really comedy

and vice versa

My creative instinct

has been butchered by too much thinking

now I'm facing catastrophe

I hate the Baltic sea

I love the north Sea

Ostend you know

Dunkirk

pivotal

very pivotal

One New Year's Eve

not far from Folkestone

I was thrown into the English Channel

by a pub owner

I was clinging on to the weekend edition of The Times

and they used it to pull me out of the water

so you could say I owe my life

to The Times

I have often asked myself

madam

if it might not have been better

had I let go of The Times

It would have saved me from all this

Life is a farce

which the intelligentsia call existence

The artist is only a true artist

when he is absolutely mad

when he has dived head first into madness

into the abyss

to discover a way of working

from Thomas Bernhard, Minetti

Very sorry to hear of Mark Wood's death. Like many others, Wood s lot was my first port of call whenever I connected to the internet.

Mark Bowles, from Piccolo

Who cares if you've read all of Hegel? 'Humanities' started sounding like a disease. 'All you people are capable of is carrying around a volume of Mandelstam'. Many unfamiliar horizons unfurled before us. The intelligentsia grew calamitously poor.

Out of habit, I would go into the used bookstore where the full two-hundred-volume sets of the World Classics Library and Library of Adventures now stood calmly, not flying off the shelves. Those orange bindings, the books that had once driven me mad. I'd stare at the spines and linger, inhaling their smell. Mountains of books! The intelligentsia were selling off their libraries. People had grown poor, of course, but it wasn't just for spare cash – ultimately books had disappointed them. People were disillusioned. It became rude to ask, 'What are you reading?' Too much about our lives had changed, and these weren't things you could read about in books. Russian novelists don't teach you how to become successful. How to get rich … Oblomov lies on his couch, Chekhov's protagonists drink tea and complain about their lives …

In the camp, my father met a lot of educated people. He never met people that interesting anywhere else. Some of them wrote poems; the ones who did were more likely to survive. Like the priests who would pray.

… I was already sick of all those conversations from constantly hearing them at home: communism, the meaning of life, the happiness of others … Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov … They weren't my idols – they were my mother's. The people who read books and dreamed of flying, like Chekhov's seagull, were replaced by those who didn't read but knew how to fly.

from Svetlana Alexievich, Secondhand Time (my book of the year, for what it's worth)

Behold the world, that it is a thing wholly without substance, in which thou must place no trust.

All works pass away, take their end and are as if they never had been.

Arise, arise, put off thy stinking body, thy garment of clay, the fetter, the bond.

Woe, woe unto the shaper of my body, unto those who fettered my soul, and unto the rebels that enslaved me.

Have no regret, for this place in which thou dwellest, or this place is desolate … the works shall be wholly abandoned and shall not come together again.

I no longer have trust in anything in the world.

Thou hast taken the treasures of life and cast it onto the worthless earth.

As it entered the turbid water, the living water lamented and wept.

Who took the song of praise, broke it asunder and cast it thither and thither?

I have come to know myself and have gathered myself from everywhere.

The tribe of souls was transported here from the house of life.

Who has carried me into captivity away from my place and my abode, from the household of my parents who brought me up? Who brought me to the guilty ones, the songs of the vain dwelling? Who brought me to the rebels who make war day after day?

Who has thrown me into the suffering of the worlds, who has transported me into the evil darkness? So long I endured and dwelt in the world, so long I dwelt among the works of my hands.

You see, o child, through how many bodies [elements], how many ranks of demos, how many concatenations and revolutions of stars, we have to work our way in order to hastened to the one and only God.

What liberates is the knowledge of who we were, what we became; where we were, whereinto we have been thrown; whereto we speed, wherefrom we are redeemed; what birth is, and what rebirth.

Adam, behold the world, that is a thing wholly without substance in which though must place no trust. All works pass away, take their end and are as if they had never been.

Arise, arise Adam, put off thy stinking body, thy garment of day, the fetter, the bond … for thy time is come, thy measure is full, to depart from this world …

I sent a call out into the world: Let every man be watchful of himself. Whosoever is watchful of himself shall be saved from the devouring fire.

Have no regret, Adam, for this place in which thou dwellest, for this place is desolate … The works shall be wholly abandoned and shall not come together again.

From the day we beheld thee,

From the day when we heard thy word.

Our hearts were filled with peace.

We believe in thee, Good One,

We beheld thy light and shall not forget thee.

All our days we shall not forget thee,

Not one hour let thee from our hearts.

From various Gnostic texts, from Han's Jonas's Gnosticism