Randy Metcalfe reviews Wittgenstein Jr at Transformative Explications.

Category: Uncategorized

A piece I wrote on music and Wittgenstein Jr for Largehearted Boy.

I'll be reading from and discussing Wittgenstein Jr in Cambridge on Thursday 30th October with David Winters at Heffers Bookshop, from 6.30-8.00. Tickets here.

I'll be doing the same thing alongside Andrea Brady at the Serpentine Gallery, London, on Saturday 1st November, from 3.00-4.30. Info here.

And I'll be doing it again at the Newcastle Centre for the Literary Arts on Thursday 6th November, from 7.15-9.00. I'll be reading with Evie Wyld. Tickets here.

Drew Smith reviews Wittgenstein Jr at The Daily Beast.

Juliet Jacques reviews Wittgenstein Jr for New Statesman.

Wittgenstein Jr featured is one of the books to look out for in September, according to Flavorwire and Ask Men.

Dogma now out in Turkish translation.

New interview with me by David Lea at the London Review of Books blog.

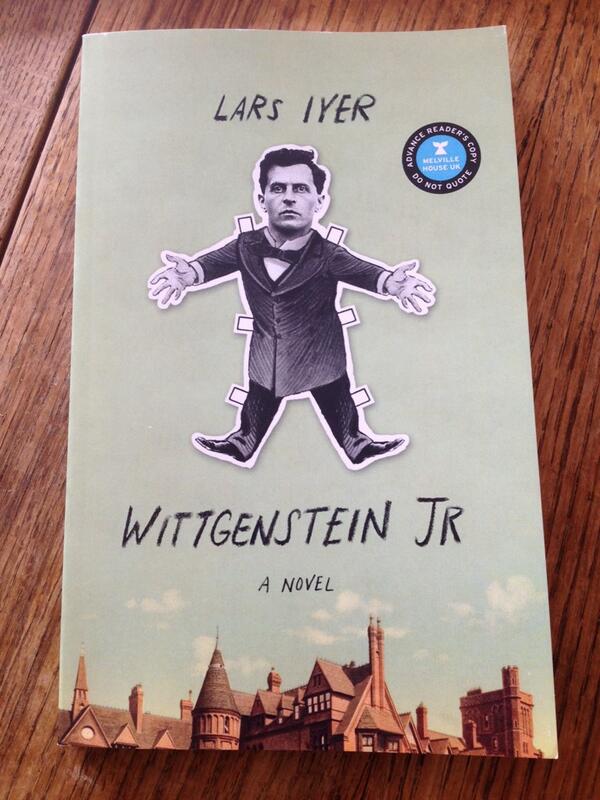

Wittgenstein Jr is not out until 4th September, but it's available now from Melville House.

Starred review for Wittgenstein Jr at Publishers Weekly.

First review of Wittgenstein Jr, at Kirkus Reviews.

London launch for Wittgenstein Jr, with Ray Monk, London Review Bookshop, 28th August, 7PM. Book tickets and more details here.

I don’t like realistic and natural descriptions of people, even if they are magisterial like those of the 19th century, in Stendhal and Flaubert, or in a different form, like Tolstoy’s and Dostoevsky’s. It’s alien to me. I like strong outlines, like in Romanesque art. That is to say, the outline gives form, and inside the form, the reader or observer can come to meet the person. I was searching for a different epic, for what I found as a reader of Medieval epic poems; they let me live in the personalities. I intended to contemporize them as well in My Year in the No-Man’s-Bay, in Crossing the Sierra de Gredos, and in At Night Over the River Morava. These, at their core, are medieval novels, epic poems more than novels. In this sense, I don’t believe as much in the novel as in the epic, the story that comes from afar and is balanced toward the distance. In other words, I am an enemy of psychological writing.

[…] Permeability is what’s decisive. What it says is that the writer converts into a figure in transit, through which many things pass. But who has achieved that? I don’t know; Homer sometimes, and Georges Simenon (laughs). Sometimes William Faulkner. Literature, in reality, does not progress; it has variants. To write like Simenon now cannot be done. Once I said, a long time ago, “sigh…if only I learned how to write like Chekhov, stories like that, theatrical works like Anton Chekhov’s. Then someone said to me, “But that already exists! It’s not lacking. Write what Chekhov transmitted to you, about his world, his movement and rhythm, his quality, and above all about his shaking.” One time I said a great writer closes his path to his successors, but only so they can find their own.

Peter Handke, interviewed

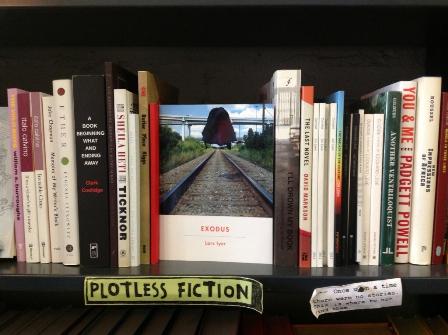

Exodus recommended in The Skinny.

New philosophical interview at Review 31. With Marc Farrant.

Picture by Janet Joy Wilson.

The great David Winters reviews Exodus for The Independent.

The interview with Neil Denny broadcast on his Little Atoms show on Resonance FM on 19th April is now available as a Podcast on iTunes.

A favourite review of Dogma, from Hey Small Press, a publication that has disappeared from the internet:

Dogma by Lars Iyer

Publisher: Melville House Publishing

Publication Date: February 2012

ISBN: 978-1612190464

Paperback, $14.95

The United Kingdom has a Thomas Bernhard, and his name is Lars Iyer. Dogma is the second novel in a trilogy that began with Iyer’s first novel Spurious. It is the story of two Kafka-obsessed windbag British intellectuals, W. and Lars, on a mission to devise and hawk an odd, spartan meta-philosophy they call Dogma. W. is a hardheaded and hyperbolic Jewish professor who spends much of his time devising eloquent ways to insult his colleague Lars, a slovenly and depressed Danish Hindu with an inexplicable obsession with the mysterious Texas blues musician Jandek. The two are unabashedly referential, pulling inspiration from (and speaking constantly of) numerous avant-garde artists and directors: Dogma is a reference to filmmaker Lars Von Trier’s manifesto Dogme95. W. seems to be constantly projecting Werner Herzog’s film Strozsek on a wall in his house. They quote Bataille, Pascal, Leibniz, Rosenzweig, and Cohen. Dogma is hilarious and bleak and loaded with illuminating, brilliant passages, and Iyer’s rapid-fire staccato prose is well-suited to the task. For those who like their dark, difficult books to be funny.

'Last Clowns Dancing': Tom Cutterham very interestingly reviews the trilogy in The Oxonian Review.

Vanessa Palmiero reviews the Italian version of Spurious at Flaneri.

Press Kit interview for EXODUS

At its core, what would you say Exodus is about?

Exodus is my attempt at a ‘big’ book, a kind of comic Book of Revelations, its philosophy-lecturer characters careening through Britain in the midst of the financial collapse of the late 2000s. Inspired by a range of maverick thinkers – including Žižek, Badiou and Dolar, who feature in the novel – its protagonists dream of taking a fierce last stand against the forces of capitalism, which are arrayed against the life of the mind. Is it really easier to imagine the end of the world than getting rid of capitalism? Anticipating the Occupy movement, and the British student demonstrations of 2011, Exodus is a love letter to would-be thinkers and maverick utopians everywhere.

Where did the idea for the trilogy come from?

W. and Lars are characters I developed as comic relief on my philosophy blog. I meant them to amuse my friends, including the real-life prototype of W. But they began to draw a much broader audience, and I decided that they deserved their own book – and even a series of books – which, although constantly rooted in the cartoon-like intellectual slapstick of the characters, would also bear upon larger concerns.

Why did you decide to write a trilogy? Do the three books need to be read in sequence, or can a reader pick up Dogma or Exodus?

Why a trilogy? I felt that the exuberance of the characters merited more than one book. And there’s the exuberance of the style, too, as crazed as that of Dr Seuss, which is able to encompass virtuosic insult, apocalyptic lament, choice quotations from favourite writers, lyrical accounts of the great thinkers, and potted histories of capital flight and industrial decline. I had a sense that the delirium of my books might measure up to the delirium of our times. That’s what led me from the pared-down settings of Spurious to the much more expansive panorama of Britain in Exodus.

There’s no need for the novels to be read in sequence. Each of them (and pretty much each part of them) is a fractal of the whole. From section to section in my novels, I wanted to retain the immediacy of a daily strip-cartoon like Charles Schultz’s Peanuts, in which characters and situations would have to reveal themselves very quickly to their audience.

How do you feel about the frequent comparisons to Beckett that you've received from critics?

Who wouldn’t be flattered to be compared to Beckett? There are similarities indeed between my trilogy and Beckett’s Godot: both concern a pair of bantering frenemies, eternally wavering between hope and despair. But my novels are more fixed in a particular place and a time than Beckett’s fiction. They’re part of a postmodern age, an age of mass media, in a way that Beckett’s are not. My characters surf the ‘net and play computer games. They read gossip magazines and watch trash TV. These are not incidental details. My characters are very much on our side of the great mountain range of modernism.

I would make a similar claim with respect to the flattering comparisons which have been made between my work and Thomas Bernhard’s. My characters, unlike his, are engulfed in ‘low’ culture. They experience the distance between the contemporary world and the life of the mind much more acutely. The intellectual pursuits of W. and Lars are that much more absurd, that much more anachronistic, because they are undertaken in no supporting context whatsoever. Bernhard satirises Viennese high culture; but in Britain, there is no high culture to satirise. W. and Lars are almost alone in their interest in philosophers like Rosenzweig or Hermann Cohen. The thinker-friends they admire are likewise entirely cut off from contemporary British life. There is pretty much no interest in Britain, academic or otherwise, in the figures W. and Lars venerate.

W. and Lars remind me of Roberto Bolaño’s quixotic characters in The Savage Detectives, who are dedicated to living a poetico-political life – the life of Rimbaud or the Surrealists, the life of the Beat Generation – in a world in which poetry and left-wing politics are utterly irrelevant, and apocalypse waits round the corner. The story I tell of the lost generation of former Essex postgraduates reminds me most of all of the diaspora of Bolaño’s Visceral Realists. W. and Lars are as quixotic, hopeful and deluded as Bolaño’s Robert Belano and Ulysses Lima, driving into the desert. But W. and Lars are not even part of a movement, as Bolaño’s characters were. They’re quite alone… As alone as Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, albeit in very different way.

How do you see the future of philosophy & academia? Is it as bleak as it seems to be in the book?

In the last couple of years, we have adopted the U.S. model of higher education in Britain, effectively privatising the university, and vastly increasing fees. Graduates will be burdened with huge debt, and people from poorer backgrounds have been discouraged from academic study. In Britain, there’s another twist, which Mark Fisher has called ‘market Stalinism’. Bureaucracy and managerialism are rife, and audit-culture has spread throughout the academy. Older models of teaching are being abandoned in favour of a kind of professional training. These are desperate times! End times!

HTMLGiant shine the 'Author Spotlight' on me for a review/ interview. Grant Maierhofer asked the questions.