[Draft of an article published in ANGERMION (de Gruyter ) XIV (Dec 2021)]

The Music of Friendship: Nietzsche and the Burbs

The opportunity to discuss your own work as a novelist is a curious one. ‘Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards’, wrote Kierkegaard. It is only in an essay such as this one that I can begin to understand a literary project that occupied me for several years. We only know what we were working on once we’ve finished work; we can only know our pro-ject – etymologically, what we throw ahead of us – as a re-ject, as what is thrown behind us. Writing is lived; it is experiential and experimental, a projection into a future whose course is unknown. But understanding is retrospective; it presupposes a corpse.

This means that I confront my own work as a kind of Sphinx, an enigmatic monument the riddle of which is hard to solve. Literary fiction plays a different language game to an essay of the kind I am writing, particularly with regard to what might be called the materiality or even musicality of its language: its rhythms and sonorities, its grain. Yet it is the exactly the music of my work – both the imaginary music I write about and the music of its prose – that is my topic.

What follows is my attempt to respond to the Sphinx, in which I remember the music of friendship at play between my characters, but also in early relationships of my own to which I want to pay tribute. This is an answer to her riddle – it’s a way of understand what I was doing, even as I know there could be many others.

*

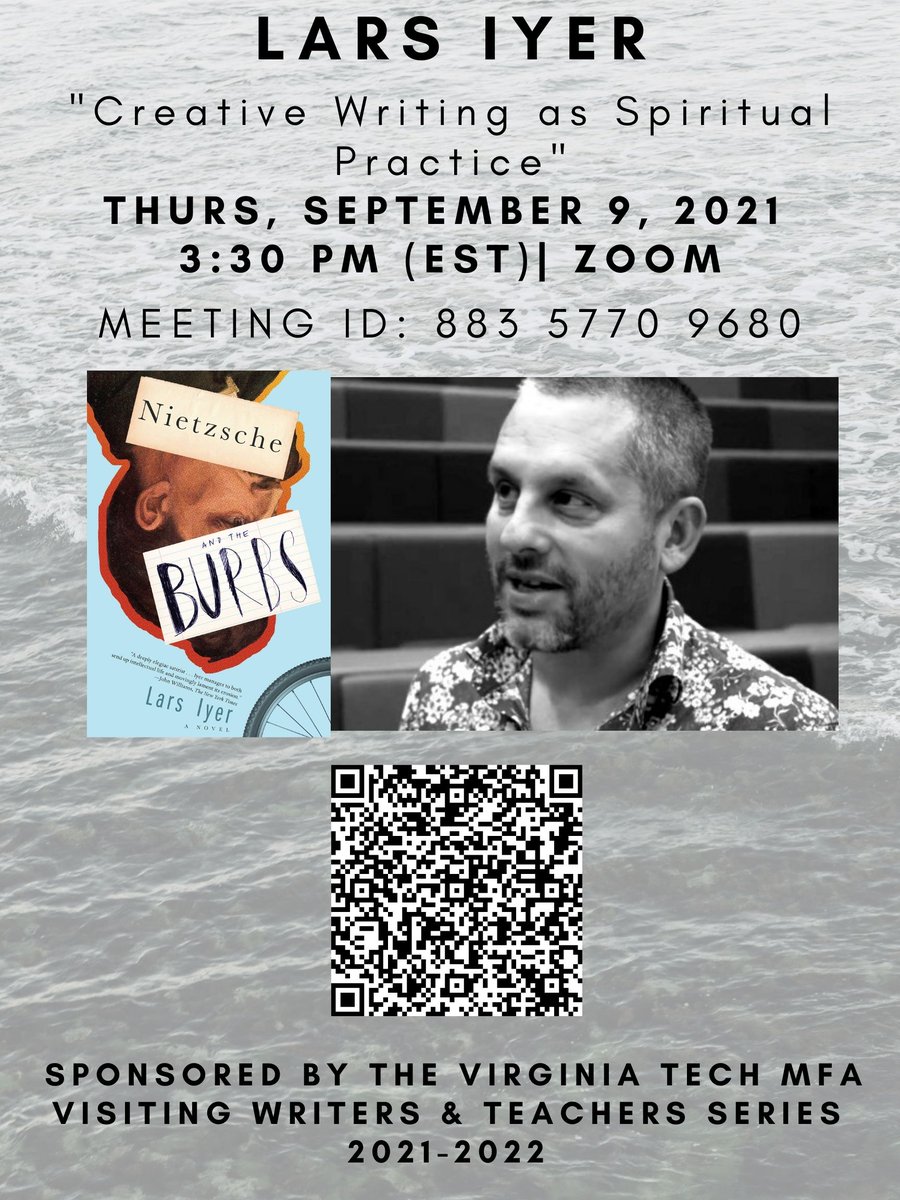

Nietzsche and the Burbs (2019) is the second in a trilogy of novels, each of which takes a historical philosopher as its central figure, introducing an avatar of them into the contemporary world. The anachronism of these characters is the point; in each case, the reborn versions of the real Wittgenstein (Wittgenstein Jr, 2014), the real Nietzsche and, in my next novel, the real Simone Weil live at a freeing remove from their surroundings, allowing them to diagnose and attempt to address the ills of our present. Their charisma – the fascination they elicit from those around them – is a result of their seeming to come from elsewhere.

The novel is set in the contemporary UK among seventeen year old sixth-formers just about to take their A-levels. One of its central characters is a reborn Nietzsche, now a privately-schooled nineteen-year-old boy of partly German descent, who, following his father’s death and his own mental breakdown, joins a local comprehensive school sixth-form to complete his A-levels. He’s aloof, quiet, but is inveigled by some of pupils of his new school – a group of friends bored and dissatisfied by their suburban lot – to become the lead singer of their band. The friends are looking for a leader, a role which Nietzsche, as they nickname him, is reluctant to take on. But he does set them a salutary example, exuding philosophical seriousness and depth and encouraging them to deepen their supposed despair, allowing them to confront the nihilism of the suburbs.

My main characters – Art, Paula, Merv and Chandra (the narrator) – spend their time pondering life and its meaning, lamenting their suburban fate, discussing their favourite music and films as well as getting high – all that ordinary teenage stuff. The novel traces the catalytic effect my character Nietzsche has on these friends, especially as it revitalises their music-making, guiding them towards a new ethos, a non-nihilistic way of living. The title of my novel, Nietzsche and the Burbs, is the name the band takes after Nietzsche joins them as lead singer.

*

The novel is set Wokingham, a commuter-belt town about thirty miles west of London, which is part of the so-called knowledge economy spine, the so-called innovation engine, that runs through the Thames Valley. You can find most of the big multinational businesses there; tech companies thrive, along with the financial and business services firms, the pharma-bio industries, the great retail firms … There’s a huge demand for highly educated workers, a brain economy of software engineers, telecoms people and commercial staff. Housing estates are solutions to the growth-zone problem, the family-friendly problem and the easy-commute problem …The new houses aren’t exciting – they are mostly Georgian-style boxes – but they don’t need to be. Wokingham’s a pragmatic town, where there’s business to be done; aesthetics is a secondary concern.

My teen characters stand out. They don’t want to do what they’re supposed to – pursue a vocational course at uni, find an office job, settle down. They don’t want to make the suburban adjustment, and accept that this is the only world there can be. My teens have a sense of being totally managed – suburban life is paranoically controlled. Nothing, they feel, is allowed to happen. There’s no spontaneity or otherness. Pseudo-event follows pseudo-event; the future feels totally programmed, prescribed, modelled – indeed, it barely seems to exist at all. Nothing anyone says seems to mean anything – words like family, home, friend, have been hollowed out, seeming to only parody older meanings. Their families live through abstract representations that cover up a general evacuation of meaning. Homogenisation holds sway. Everyone, no matter what their origins, seems to become alike. If there are deviations – eccentricities, idiosyncrasies – they are permitted ones; there’s a way to be fun, wacky, surprising and so on in the suburbs. There’s a way to be diverse – to be gay, to be foreign, to be working class.

For my teens, formal education is mere processing, leading everyone into the office. There are a few maverick teachers at their comprehensive school: a Marxist economist, a doomy geographer obsessed with climate change, a Thomas-Bernhard reading émigré, but my teens informally educate themselves, learning from counter-cultural role models and musicians: Arthur Rimbaud and Kurt Cobain, Nadya Tolokno from Pussy Riot and the musician and former Orthodox Christian monk Jason Marler.

My teens talk despair and suicide. They seethe with dislike for the drudge-like masses who populate their sixth form and yet feel inferior to the private school children they come across. They’re aware of the cultural capital they lack, of the great gaps in their education. They know their grades have been inflated, that their passage through school has been too easy and their time at university will be the same. What appeals (though they might deny this) is an aristocratic mode of existence; a sovereign splendour that would place them beyond the doings of the mundane world – beyond its blandness and fakery.

My teens are intellectuals of a sort, full of inchoate philosophical questions, but also crave excitement – altered states through drunkenness and drug-taking. Sometimes they search for peace, too – for open time, for interregna of various kinds: slow cycle rides, lying in the grass, smoking weed, truanting. And they have nascent artistic desires, which drive them to make music. They want to redeem their lives in some way, to make sense of their lives in the suburbs.

Enter my character Nietzsche – subdued, charismatic, ardent. He intensifies and focuses the discontent of my teens. He talks tersely about nihilism and the death of God and expresses suspicion of pity and compassion. He thinks my teens’ despair is sham and should be driven deeper. Crucially, his very presence makes them want to reform their band and to recruit him as lead singer. The novel builds towards the first gig of the band, Nietzsche and the Burbs. As the band rehearses, the teens begin to hope that their music-making might help them to overcome day to day suburban nihilism, allowing them to transfigure their lives, elevating the contingencies of their existence into something necessary. The band come to understand their music-making in philosophical terms, as a way of transforming their affective lives, allowing them to become conduits of revivifying forces.

*

Let me step back to the historical Nietzsche in order to understand the band’s ambitions.

The real, for the real Nietzsche, is in a constant state of becoming, without purpose or goal. Process is primary, not stable entities, which form and dissolve within a larger chaotic field. For Nietzsche, human life can be sustained by establishing horizons within which a community can live. These horizons are, in a sense, lies – ways of concealing chaos from ourselves. But lies are, Nietzsche argues, more valuable than truth when it comes to communal flourishing, since the lack of purpose or goal, the fact that meaning isn’t simply given, is too much to bear.

The importance of music, for Nietzsche, lies in its role in laying out the horizons in question – composing chaos into order. This is because music is able to operate directly on our bodies – on the multiplicity of passions that each of us is. We are not primarily minds or souls, but complexes of passions which, in turn, reflect deeper drives and impulses that work in and through us. These drives and impulses are manifestations of becoming – of the chaos that Nietzsche calls the will to power.

Nietzsche uses this term to refer to the fundamental struggle of becoming with itself. The will to power is the war among all things for dominance and self-overcoming. Particular entities exist insofar as they are moments of the will to power, in and through their antagonistic relations to other entities. This struggle holds sway among the passions, too. Each passion is a moment of the will to power and, as such, strives to overcome other such moments. Passions conflict. The danger is that the internal struggle of the passions leads to chaos. They need proper regulation – the body as such needs to be trained and marshalled.

*

This is where music comes in.

Traditionally, philosophers have argued that we need to exert rational control over our bodies and its passions, working to bring them into line with our intellect. However, Nietzsche argues that the role of rationality itself is relatively superficial. He argues that human beings are primarily affective rather than thinking beings and that our passions are barely open to self-examination at all. We are unable to recognise or understand the way we are shaped by drives and forces, let alone order these passions rationally.

So how, then, can we regulate our affective lives? For Nietzsche, music has a particularly strong effect on the passions. Musical modulation allows the passions to be co-ordinated or ‘rank-ordered’ as part of a harmonic whole. The dissonance of the passions can be harmonically resolved through melody, which trains and disciplines the human body not only individually, but collectively. In this way, musical discipline may produce an appropriately harmonized ethos for a community.

This is how music can be understood to transfigure the chaos of the real, to provide a communal form in the flux of becoming. Unlike rationality, which seeks to supress the passions altogether, musical harmony preserves passions in their difference, maintaining the internal tension of the body as part of a higher harmony.

*

The role of musical training is particularly important in the wake of what Nietzsche calls the ‘death of God’. Formerly, human passions were constrained and ordered by subordinating them to a rational God and rational cosmos. With the cultural decline of Christianity, this internal regulation – a whole system of instincts – begins to fail, and with it that sense of meaning, purpose and direction which comes from having a horizon within which to live.

Nietzsche isn’t nostalgic for Christianity which, for him, denigrated life, unfavourably measuring it against an eternal, rational order. But he’s also fearful for the future. New movements of thought such as positivism, materialism and utilitarianism threaten to perpetuate the unhealthy aspects of Christianity, preventing its final collapse and the possibility of rebirth. European civilization is no longer able to rank or hierarchize the passions appropriately, preventing that enlivening inner struggle on which a genuinely new, post-Christian psychic and communal ordering depends. There is the temptation of passive nihilism, taking refuge in pessimism and resignation – in a rejection of any hope in the world. The counter-temptation of active nihilism, exemplified by the fiery characters of Dostoevsky, might seem more positive, but seeks to fruitlessly destroy the world rather than prepare the way for anything new. It is, at best, merely transitional. But Nietzsche’s greatest fear is that we will lapse into the state of being of the last human [letze Mensch] – a banal, low-intensity hedonism, a self-satisfied happiness that is the consolation of those whose passions no longer struggle.

My teens see the last humans all about them, in their snacking and surfing peers in the sixth-form common room and in their parents, busy commuting to and from the offices of the Thames Valley ‘knowledge spine’. They themselves move between active and passive nihilism, depending on circumstances. But they sense the danger of making the suburban adjustment and giving way to low-intensity contentment. It is my Nietzsche who makes them realise what they half-know: that music-making opens them to intensities which suburban life cannot manage into quiescence. Music has, all along, loved for them and hated for them, desired for them and yearned for them. They’ve talked music for years. But music-making provides my characters with the goal they lacked, helping them to coordinate their passions and reshape their affective lives. Their band, with Nietzsche at the helm, allows them to become conduits of larger, trans-suburban forces. This is how they might overcome nihilism.

*

Before Nietzsche joins them, the band’s music is a muddle. We see them trying out a variety of different kinds of music, including doom or stoner metal and dub, but it all seems culturally exhausted; it’s all been done before. They lack the capacity to believe in themselves as musicians – and to believe in that they can create anything new. But when Nietzsche takes up his role as their a singer, they feel their way into an open-ended, improvisational music practice.

What do they sound like? They’re a five piece: Chandra plays guitar, Paula, bass, Merv plays marimba – an unlikely instrument for their combo – and Bill comes to play drums. Art, in whose bedroom they rehearse, produces them and adds effects – his role is similar to the ‘non-musician’ Brian Eno in Roxy Music and elsewhere, modifying the sound of musical instruments through technological treatments.

Initially, the band play a kind of doom metal, drawing on the slower, sludgier elements of Black Sabbath’s first six albums (1970-76). Doom is introverted, characteristically melancholy, emphasising sub-frequencies and minor key melodies, with lyrics focused on melancholy, madness and the occult. It is characterised by heavily distorted, lengthily sustained guitar chords and slow-building monolithic riffs, giving the music a ritualistic, hypnotic feel. My teens also show an interest in so-called ambient metal, an offshoot of doom, exemplified by Earth’s Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Edition (1993), a minimalist, beatless album of drone and feedback, entirely lacking vocals or verse/ chorus structure. Ambient metal reflects the influence of American minimalist composers like La Monte Young and Terry Riley just as much as Black Sabbath who make use of repetition and circular structures, producing pieces of long duration and little melodic progression foregrounding drone. My teens also admire a related American composer, Pauline Oliveros, who works directly with drones, encouraging ‘deep listening’, focusing on microscopic subtleties in sound.

My teens are also interested in beat-driven music, too. They try their hand at dub reggae, which, similar to doom and ambient metal, is immersive and bass-driven, focusing on texture and timbre. Dub is a producer’s or engineer’s genre working with completed songs, largely erasing the original vocal track and other instrumentation, leaving a raw rhythm track, over which extra sound effects might be added, filtered through reverb and echo units. It characteristically has a broken, unfinished feel, with disorientating, thickly textured shards of sound floating above an elemental, throbbing bass pattern and with fragments of lyrics evoking biblical apocalypse and Rastafarian belief. Paula, the bassist, finds herself reverting to classic reggae basslines when she tries to play something new. Art, for his part, shows an interest in dub production techniques, even attempting to recreate Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s famous Black Ark studio in his bedroom.

The band move on from doom and dub (and their unlikely-sounding hybrid of the two) towards an expansive and weightless kind of ‘kosmiche music’, the open-ended improvisational music of Can and other West German bands of the early 1970s, which broke away from the song structures and the blues scale, drawing on electronic music and avant-garde composition, making use of synthesizers and tape-music techniques. Kosmiche bands worked with drawn out structures without the theatricality and bombast of contemporaneous progressive rock, their musical collages often anchored by hypnotic, forward-flowing rhythms – the famous minimalist, syncopation-free ‘motorik’ beat first heard on Can’s ‘Mother Sky’ (from Soundtracks, 1970) and on the first, eponymous, Neu! album (1972). But it is the hazy, spaced-out soundscapes of Can’s Future Days (1973) that seem to most strongly influence my teens, with its scratchy, funky guitar, oceanic synthesizer, its lilting, intricate rhythms and buried, whispery vocals. The music of Nietzsche and the Burbs, the band, is characterised by the same serene tranquillity, the same egoless, ensemble playing, with its balmy inventiveness, its currents of warmth.

Finally, just before the gig, their sound echoes Miles Davis’s jazz-fusion band of the mid ‘70s as recorded on the 1975 albums Agharta and Pangea, which mixes free and modal jazz with psychedelic rock and rhythm and blues. Vamps and themes rest upon the polyrhythmic complexity of the rhythm section, a constantly evolving muscular groove. Much heavier, denser and unrelenting than Can’s Future Days, the music seethes and boils relentlessly, opening periodically into sonic equivalents of vistas — into unmetered flux.

*

What do these kinds of music have in common? They all come from, or are rooted in, the countercultural explosion of the ‘60s, when music had an ability to define a time, playing a leading role in communal revolution. ‘60s music – psychedelia, free jazz, reggae – had a utopian edge, part of a quest for new forms of social organisation – be it the commune (psychedelic rock) or the ‘repatrination’ to Ethiopia (reggae). Music-making in this period revived the old dialectic between bohemian creativity and bourgeois existence – between the struggle for a meaningful rather than comfortable life. Heightened experience was opposed to settled conformism; immediate gratification and expressive intensity to mundane self-preservation; and abandonment and exuberance to the flabbiness of middle class life. If, later on, the counter-culture came to collapse into narcissistic individualism and consumerism; if music no longer played a leading role in culture at large, its power of general transfiguration having withered, it continued to inform the imaginary of the strands of musical practice my teens admire.

What of the qualities of the music itself? Common to doom, dub and Miles Davis’s jazz-fusion is the use of pulsing, droning rhythms and the foregrounding of songscapes over songs. They depend on improvisation, often making use of mixing desk and studio manipulation. Textural layering is crucial – an interweaving of instruments over the bottom end of bass and drums have a central role. These genuinely collective, non-hierarchical qualities are present in the music of my teens. But I would like to emphasise something else, too. At each one of their practices, the band seem to recreate their music – to transform their repertoire of songs. Each time, they seem to draw from an inexhaustible origin, an Ursprung that springs forth dynamically in their music on that day. In the historical Nietzsche’s terms, we might understand them as drawing on a well of chaos, of the will to power that lies beyond the suburban horizon. It is this welter of forces they’re able to engage through their doom- dub- drone- fusion-influenced music.

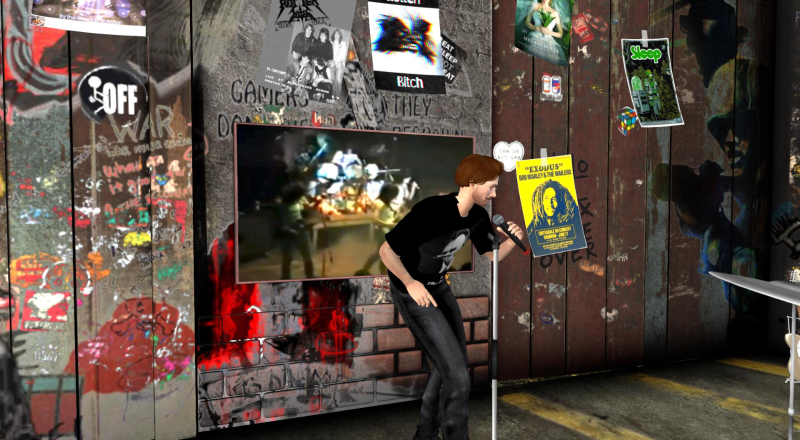

What does my Nietzsche add to this music? At first, only a whispering speech-singing, close to a murmur, drifting in and out of silence, recalling Damo Suzuki’s vocals on Future Days, which are like a mist, a spray, another element of the shimmering texture of the music. There’s also Jandek’s Glasgow Monday, which features tremulous speech-song over piano and percussion. Nietzsche’s vocals are only part of a tapestry of sound; they are but an element of the music. But Nietzsche’s speech-singing gains strength, his lyrics become more intelligible, and it seems at their gig that he really might sing for the first time. His presence – if not yet leadership – gives the band direction. Doubts about their musical direction cease; improvisatory songscapes become songs and, for all their carping, all their supposed despair, my teens come to experience music-making as a joyful, affirmatory practice.

*

Chandra, my narrator, hopes that he and his friends might redeem their suburban lives by performing and recording their music, making sense of everything that has happened to them. Their creativity affirms its own conditions – the fact that my teens were born and brought up in the suburbs of Wokingham. Music-making would allow my teens to lift every ephemeral moment of their lives out of irrelevancy and contingency by establishing its absolute importance to their creative practice. Everything that’s happened to them would now be a necessary condition of their music-making and is thereby affirmed by it.

For this reason, according to Chandra, their hometown wouldn’t be just another knot in the great sprawl of the suburbs of southeast England, but the origin of this transformative music, indeed its only possible origin, which would make it a place of pilgrimage for their admirers. What would these admirers see? A town like any other, just the same as any other, but also a town that is unlike any other because it was the condition for the music of Nietzsche and the Burbs. And maybe these pilgrims could go back to their own suburban towns and make affirmatory, transfiguring music of their own.

As such, my characters dream of collective amor fati, a love of fate that would show their audience a way of affirming the suburban hand they were dealt. This would free them from the spirit of hatred and revenge of the active nihilist, since they could thereby overcome the resentment of being born and brought up in such an insignificant, philistine place.

The historical Nietzsche would reject understanding amor fati on a model of subjective volition. The philosopher challenged the notion of individual agency, seeing the individual will as a metaphysical fiction. Although we experience ourselves as causal agents, able to effect changes in the world, the autonomous, self-regulating subject is a myth. On the historical Nietzsche’s account, the real agent of our willing is the will to power, understood as multiplicity, as a field of power differences and relations, in all its indifference and amorality. This is also case for the suburban life that my characters would affirm, since the suburbs, too, are only ultimately a moment of the will to power. In the case of both self and suburbs, the will to power is causally and ontologically primary – it cannot be contained or channelled by any particular form. Indeed, the very creativity of the will to power always involves moments of destruction, of active nihilism, as it overcomes its current ordering.

This is why my teens can seek a new psychic ordering and way of life through music. By engaging with the elemental strife of the will to power, the band’s music would allow them to order their passions, and harmonise their experience – and to do the same for their audience. Granted, such a harmonizing can never be definitive – it can never happen once and for all. There will be need for more creative destruction, for more overcoming. But their amor fati might permit, for a time, a collective power of affirmation that reshapes the system of instincts of its makers and listeners, recreating the suburbs.

*

But we need to go further still to understand what the teens seek with their music. How is it actually supposed to overcome nihilism?

For the historical Nietzsche, the ultimate test on which amor fati depends is, paradoxically, to will the world exactly as it is – to desire that everything that led up to this moment to return over and again. This is his famous notion of the eternal return.

The question that faces my characters is whether they can affirm their suburban lives with its last humans, its banality, as well as its cruelties. To really love their suburban fate means envisaging enduring it countless times. Wouldn’t this lead directly to madness, as their Thomas-Bernhard-reading teacher argues? This depends on the interpretation of Nietzsche’s doctrine. Like any other entity, according to the historical Nietzsche’s ontology, the suburbs are a changing amalgam of forces rather than a fixed, unitary thing. To desire the eternal return of the suburbs means to affirm those energies as movements of becoming, which may in turn be productive of new ways of living.

Towards the end of the novel, my teens declare themselves ready to ‘play the suburban eternity’ – to play this particular traffic jam as every traffic jam, this particular roadworks as every roadworks, this particular town as it echoes with every other town. The band plays the suburban condition in its banality and nullity, as one element of their music harmony. But they give voice to something else: the flux and becoming of which the suburbs are but a transitional formation. The band’s music would bring together both the banality of suburbs and, in productive tension with it, the exuberance of volatile, mobile energies.

How is this act of musical harmony possible?

*

For the historical Nietzsche, the strength to will the eternal return is available only to the overhuman [Übermensch]. This kind of human life wants nothing more than to overcome its present form, rejecting any accommodation with prevailing notions of happiness. The overhuman is devoted to the art of transfiguration, seeking to redeem life through creative action, opening a future beyond the monotonous rhythms of the present. As such, the overhuman cannot think of itself as an end point, as a final evolutionary stage, in the manner of the last human. The ‘over’ in overhuman should be understood in terms of a continual desire for overcoming, of a thirst for physiological, cultural and spiritual metamorphosis. The overhuman is not interested in self-preservation, in what is usually called health (including mental health) or happiness. In this way, the overhuman is aligned most closely with the will to power, expressing and discharging overfulness.

What are the conditions for the appearance of the overhuman? The historical Nietzsche sometimes suggests that the overhuman will require generations of training – of ‘breeding’ – to appear. My characters, by contrast, seem to believe they can become the overhuman at one stroke, through a titanic act of affirmation. Their dream is that their performance, fronted by Nietzsche, would allow them to create themselves and to overcome suburban nihilism.

But this collective affirmation depends on their mentally fragile frontman, which, as it turns out, is too much to ask of him. The band look to Nietzsche to lead their attempt to affirm the chaos from which the suburbs were shaped and into which they will return. Nietzsche is enable them to welcome and endure the test of eternal recurrence, allowing the band a taste of overhuman existence.

What should have happened: Nietzsche’s song. Nietzsche’s singing.

What should have happened: Nietzsche, really singing for the first time. Nietzsche, gone all melodic, for the first time.

What should have happened: Nietzsche, letting his body resound, the whole animal. Nietzsche’s voice, from his deep body. Nietzsche’s voice, deeper than thought, deeper than philosophy.

What should have happened: Nietzsche’s body singing, not his mind. Nietzsche’s body reverberating. Nothing showy, or histrionic. Just Nietzsche, using his lungs, his larynx, his vocal cords. Just Nietzsche, letting his voice resound.

What should have happened: Nietzsche’s singing, gathering intensity. Becoming richer, darker. Nietzsche’s singing, projected on the out-breath, coming from the core.

What should have happened: Nietzsche, singing joy and mourning, both at once. Nietzsche, singing pain and dissolution, both at once. Nietzsche, singing death and rebirth, both at once. Nietzsche, singing fullness and loss, both at once. Nietzsche, singing gathering and dispersal, both at once. Nietzsche, singing tragedy and comedy, both at once.

What happens instead? The task is too great. Nietzsche tries to sing, tries to bind chaos into the structure of a song, thereby recreating the suburbs for his band and audience, but his effort fails.

What really happened: Scattered words, scattered speech-song.

What really happened: Nietzsche, stumbling, staggering.

What really happened: Unearthly screaming – from his throat. A quavering. A buzzing – from his throat. Nietzsche, fitting. Nietzsche, thrashing.

What really happened: Nietzsche hit his head so hard. Nietzsche’s lips were blue. Nietzsche’s eyes were completely rolled back in his head.

What really happened: Suffering – just that. Pain – just that. Madness – just that.

What really happened: Bar-staff standing around us. Calling an ambulance.

Nietzsche loses his mind. He ends up in the locked ward of a mental hospital. A disaster, then – a failure of a gig, a failure of music-making, to overcome the suburban form.[i]

*

But where Nietzsche and the Burbs, the band, failed, Nietzsche and the Burbs, the book, might be understood to succeed.

The novel itself is ostensibly autobiographical, telling the story of how Chandra, its narrator, together with his friends, sought to transfigure the suburbs, rank-ordering their passions through music-making. As we have seen, my teens sought to affirm the conditions of their creativity, redeeming their suburban lives in musical performance and recording. Could we understand Chandra’s memoir as doing something similar in another medium? Of course, the memoir is not itself a musical work. Nietzsche warns us that words are always falsifications of becoming – a problem that is even worse when they are subordinated to logic. But Nietzsche himself wrote prose – and very musical prose at that, making use of such musical devices as symmetry, crescendo, inflection, tone, and tempo to express and affect the body. It is by placing emphasis on the musicality of his prose that Nietzsche resists the traditional philosophical view that our affects, our passions need to be brought into line with our intellect. An appropriately musical prose, his example suggests, can access, evoke and communicate the clash of drives and impulses at work in our affective lives in a manner that parallels that of music.

Is something similarly musical at work in Nietzsche and the Burbs? The novel is unsparing in its accounts of suburban mundanity – the dreariness of sixth-form and family life; it is full of bathetic detail and the bored talk of adolescents. But on the other, it is, as many reviewers have noted, notably musical in its style, not least in the way it evokes the music of the band. There is its rhythmic flow, with frequent use of trance-like repetition with variation at the level of phrases, sentences and paragraphs in a manner that can sometimes recall Thomas Bernhard. There is very frequent use of anaphora, with the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of successive clauses (‘what should have happened …’; ‘what really happened …’); as well as epistrophe, with the repetition of a phrase at the end of successive clauses. Throughout, the use of clipped sentence fragments (recalling Louis-Ferdinand Céline and William S. Burroughs) gives the prose liquidity, a rapid flow, and there are frequent meter-accentuating italics. Perhaps such a musical prose style might be understood to all the play of wilder, chaotic forces at play in the suburbs in the manner of the band whose music its describes.

*

But exactly how does it do so? Recent commentators have shown how Nietzsche’s own philosophical autobiography, Ecce Homo, sees him make use of the sonata form in order to recount his formation. He uses an overall pattern of exposition, development and recapitulation, thereby moving from dissonance and contradiction to consonance and harmony. This allows him to present the way in which his psychic order developed such that he could become the philosopher of eternal recurrence. Now Chandra’s memoir can also be understood to trace and perform a process of formation – an education of the passions that brought him and his friends to the brink of amor fati. It documents the results of musical discipline – the deliberate shaping of affective life that allowed the band to creatively engage with chaos, even as it led to their lead singer’s collapse. If Chandra were deliberately following Ecce Homo, then his memoir must likewise show a linear movement towards harmony, evidencing the musical shaping of his affective life. Is this in fact the case?

Rereading the novel, it seems that Chandra’s account of my teens’ experience seems more episodic than that. Nights of ecstasy fall back into days of boredom. Their rapture does not last; nihilism has to be overcome over and again. Nietzsche and the Burbs lacks the linearity, the telos of the sonata-form. How, then, should we understand its structure?

*

E.M. Cioran says in an interview that he finds the tone of Nietzsche’s letters completely different to that of his philosophical work. ‘When one reads the letters he wrote at the same time, one sees that he’s lamentable, it’s very touching, like a character out of Chekhov’. The historical Nietzsche may be lost in the thought of the will to power, but he’s also a ‘pitiful invalid’. His faith in his work is intermittent; he’s more vulnerable, he feels crushed by the world.

My teen characters might likewise be understood to be caught between rapture and the mundane. They can touch overhuman existence for a night, but they’ll wake into the world of last humans. They can try to affirm the will to power at play in the banality of the suburbs, but that same banality is their ineluctable horizon. My characters can get drunk enough, high enough, or wild enough with rhetoric to hold out for the musical transfiguration of the world, but they’re doomed to wake up from their dreams, even if, soon enough, they’ll start dreaming again. Suburban banality is not the last word, but nor is ecstasy; the life of my characters shuttles between the two.

Are we to understand the music of the novel in terms of this circular shuttling, this neither … nor, or is something else is going on?

*

The teens of my novel take great joy in dialogue – in the inexhaustible roundelay in which they share their so-called misery. They delight in not simply addressing their concerns to their friends and hearing them echoed back, but in collectively amplifying their discontent, letting it run wild. Much of the novel takes the form of a ‘choral speaking’, in which my teens echo one another, reaffirming and intensifying what they hear. Often, they combine their voices into the first person plural, leading to Bernhard-style hyperbolic build, to rising runs analogous to the arpeggiated flights of a jazz saxophonist. There are accelerations of tempo and the frequent use of exclamation points. Sure, there are italicised slow-downs, too – suspensions, especially in Nietzsche’s blog entries, which seem stoned, slurred, in dub. But the key to the musical structure of novel may be understood to lie in the talkative friendship of my teens – in the vibrant to-and-fro of their conversation.

As we have seen, Chandra, in his memoir wants to affirm the conditions of the music-making of his band – the way it allows my teens to engage with chaotic forces, giving them form. I want to suggest that the possibility of such engagement is first glimpsed in their dialogue, which is rooted in friendship. It is because my characters share an intimacy, a bond of trust sealed by a sense of what is important and unimportant, by what is worth taking seriously and worth deriding, by what is loveable and what is hateable, that they do more than what they accuse their peers, the last humans of doing: distorting and indeed hollowing out the meaning of words. For me, the creative practice of my teens is to be found not simply in their music, but in the exchanges Chandra records. Dialogue can become musical, accessing, evoking and communicating affective life insofar as it attests to what, for my teens, is genuine, truthful communication.

*

In his diaries, Franz Kafka reflects on the ‘merciful surplus of strength [Überschuß der Kräft]’ that allows him, seemingly miraculously, to write of his unhappiness in the midst of his despair – to ‘ring simple, or contrapuntal or a whole orchestration of changes on my theme’.[ii] Kafka doesn’t know where this surprising strength comes from, but it is the source of his writing, its Ursprung. Something similar could be said about my character’s ability to speak. They’re ostensibly unhappy, frustrated and bored by the suburbs; their futures seem bleak; they fear climatic collapse and economic ruination, and yet they’re always able to share their unhappiness with their friends – more, they are even able to ring changes on it, hyperbolising it, giving themselves over to collective rants. As Edgar says in King Lear, ‘The worst is not, so long as we can say, "This is the worst"’’; this capacity to speak, to respond to likeminded others, lightens the doomiest mood.

Such a capacity for dialogue belies the reported banality and dreariness of my teens’ suburban experience. They might feel managed, processed and homogenised, they are nevertheless able to give voice to this feeling, to share it and thereby triumph over it. They might feel overwhelmed by suburban meaninglessness, but they can communicate perfectly meaningfully. In this way, nihilism is overcome through the ‘merciful surplus of strength’ to which Chandra attests, even prior to their musical project.

How should we understand, then, the overall structure of Nietzsche and the Burbs, understood as Chandra’s memoir? How does it help him accomplish the transfiguration that was also the aim of the band? It is not written in a linear, sonata form – but nor is written as a circular shuttling between lows and highs. For the teens’ lows are shared in inventive and lively conversation; hatred and despair are thereby lightened. The letter of what my teens say is born by a vibrant, even affirmative spirit: the spirit of their friendship as it allows them to share and amplify a perception of the world.

My Nietzsche reprimands his bandmates for talking of their misery too lightly. But such lightening is unavoidable for my teens it depends upon the ‘merciful surplus of strength’ that animates their exchanges. Nietzsche’s quietness and isolation means he’s never part of the roundelay of my character’s chatter. Indeed, this is one of the things that contributes to his madness. When he finds a companion, Lou, with whom he can talk, she leaves him. For Chandra, Nietzsche’s insanity results from the raw chaos of the will to power to which he is exposed when he tries to sing at the gig. But it is just as plausible to attribute it to Lou’s breaking up with him, which makes him into a ‘pitiful invalid’ who can no longer share and thereby lighten his misery.

*

The celebration of friendship might not have been Chandra’s explicit aim in writing his book, but it’s omnipresent. As I have suggested, it is in the teens' dialogue that we can find the amor fati that they seek by way of their music-making. Their dialogue already allows for a quasi-musical ‘composition’ of chaos; it is a way of shaping a communal horizon that makes their lives liveable.

Perhaps this is why Art was quite right to suggest the morning after the gig that ‘the band was the obstacle. Nietzsche was the obstacle’’, and Chandra was similarly correct to quote in response the historical Nietzsche’s fictional character Zarathustra, when he turns to his admirers and says: ‘You had not yet sought yourselves; and you found me. Now I bid you lose me and find yourselves’. In the final scene of the novel, the teens find themselves by going beyond music-making to life-making by deciding to live communally. Nietzsche’s passage through their lives was the occasion for their laying claim to the ‘merciful surplus of strength’ that always and already protected them from suburban nihilism.

And this, indeed, is how I look back on my own suburban life as a teen in the suburbs of Wokingham. The suburbs came alive when my friends and I could share our discontent – when we could ring changes on our boredom. That, for me, is where the transfiguration of the suburbs occurred: where nihilism was overcome if not once and for all then at least temporarily – for a wild evening, for a laughing afternoon. Writing the novel, I wanted to remember the creativity of such exchanges, when we were otherwise pressed up against the dreariness of sixth-form life and the stress of our impending exams; I wanted to affirm the capacity to improvise on the theme of suburban banality.

My characters are always ready for hyperbole – for some grand pronouncement about the end of all things, or some fiery new revelation of hope, thereby whipping up ennui into rapture. They’re ready for humour, too – for laughing at the absurdity and imposture they see around them. And it is this desire to communicate, speaking and laughing with others, that is the clue, I think, to understanding how the form of Nietzsche and the Burbs – its overall musicality – constitutes my own act of amor fati, a way of affirming my own formative years in the suburbs. Its musical features – trance-like rhythms, moments of accelerating hyperbole, dialogue-roundelays – attest to the friendships that were the condition of my transfiguration of the suburbs, allowing me to engage with intensities beyond their suburban ordering.

[This essay is based on a talk I gave at Queen Marys College back in Autumn 2020)

[i] But is it a failure? In his generous reading of my novel, Rüdiger Gürner suggests my Nietzsche is lost in rapture rather than chaos; that he hears an Übermusik in his rapture, a music intended only for the hearing of the Übermensch – a music beyond music, beyond dissonance and consonance, a music beyond madness … (Gedankenklänge – oder: Tanz der Denkschritte: Nietzsche und die Musikalisierung der Reflexion‘, unpublished paper, 2020.) Perhaps; but this is not something our narrator tells us.

[ii] Kafka, The Diaries of Franz Kafka, 1914-1923, translated by Martin Greenberg (New York: Schocken Books, 1948), 183-184